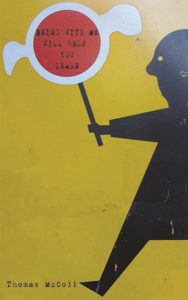

Being With Me Will Help You Learn

In his first full collection of poems and flash fiction, Thomas McColl demonstrates the truth of Seamus Heaney’s remark that poets are distinguished by their ability to “notice things.” These fifty-six pieces are notable for their acute observation and unconventional treatment of a variety of topics.

In his first full collection of poems and flash fiction, Thomas McColl demonstrates the truth of Seamus Heaney’s remark that poets are distinguished by their ability to “notice things.” These fifty-six pieces are notable for their acute observation and unconventional treatment of a variety of topics.

In the poem “I”, a rule of grammar, arguably, symbolises the instability of personal identity; with e.e.cummings as a precursor perhaps, the narrating personal pronoun reveals that he is threatened with demotion to lower case for the crime of considering himself the most important person in the world. In ludic verse, he wonders when his sentence will begin but then realises that it had already begun “in the previous sentence”. Consoled by the promise of an exclamation mark for good behaviour while incarcerated, the narrator reflects,

An i followed by an exclamation mark

is almost a capital i, just once removed [,]

before announcing his intention to demand the compensation of an exclamation mark. Not only that, he requires the restoration of capitalisation once his application to be the most important person in the world is approved. Such restitution would clear his name,

so everyone can see

the gods at last are pleased with me.

This closing couplet hammers home the narrator’s self-righteousness all the more effectively for being the second of only two rhymed lines in this otherwise unrhymed poem.

In “Pervert”, the narrator’s identity is hijacked by his new neighbours’ campaign of intimidation. That abuse is so relentless that, shades of Stockholm syndrome, he begins to side with his tormenters and to doubt his own innocence. His unemotional recitation of incidents is at odds with the barbarity of his treatment: phlegm and used condoms delivered through his letter box; being threatened, shunned and regarded “with contempt and disgust”; having the word “PERVERT” daubed on his front door – a mark of Cain, emblazoning his disgrace for all to see. Even the council seemingly conspires against him, exceptionally permitting villagers to play loud music at night so that sleeplessness may intensify his waking nightmare. Rather than resisting this onslaught, the narrator is persuaded that he deserves to be punished. The concluding stanza delivers the punchline:

And now it’s me

who’s beginning to see

it as some kind of sign.

Xenophobia in small communities is an uncomfortable truth explored in this vers libre with occasional rhymes. The pattern of the four-line first stanza deftly complements its sense, with a one-word third line sandwiched, or left hanging, much like clothes left hanging on a washing line, between two much longer lines.

In other pieces, McColl turns humorous attention towards contrasting attitudes towards the passage of time, such as when dreaded as a deadline by a hard-pressed office worker, or suffered as a theft by a flat owner and enjoyed as a holiday destination in a time-travelling future. He also takes a swipe at the absurdities of bureaucratic overkill in a scenario where pedestrians are compelled to wear number plates. In a flash fiction demonstrating the slipperiness of definitions, he highlights the difficulty of establishing a moral centre of gravity, reckoning that competing ideologies are defined and underpinned by their very opposition; in these terms, each would lose its rationale should the other cease to exist. There is much to savour in this collection as the poet satirises individuals and attitudes in a mosaic of writing composed in McColl’s often quirky and always inimitable style.

Leave a Reply