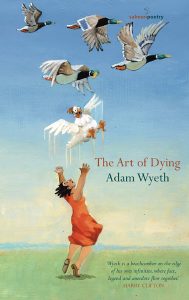

The Art of Dying

The Art of Dying would seem an incongruous title for Adam Wyeth’s astonishing new poetry collection, because it is so richly alive with nature’s characters – personified trees, ducks, Mafioso foxes… But two particular characters give the title its meaning: a man and his dying father. Wyeth is already a lauded poet, his previous work having been Highly Commended by the Forward Poetry Prize panel; it is clear from his references to Jung, Yeats and Rumi, that he is drawing from a broad knowledge of myth and language.

The Art of Dying would seem an incongruous title for Adam Wyeth’s astonishing new poetry collection, because it is so richly alive with nature’s characters – personified trees, ducks, Mafioso foxes… But two particular characters give the title its meaning: a man and his dying father. Wyeth is already a lauded poet, his previous work having been Highly Commended by the Forward Poetry Prize panel; it is clear from his references to Jung, Yeats and Rumi, that he is drawing from a broad knowledge of myth and language.

Like so many poets before him, travel becomes an act of contemplation and renewal; in “Solstice Drive”:

Rows of houses beetle past on a carousel.

An electric flatline quivers on the horizonthen fades, as if my returning has reversed time [.]

Wyeth has a talent for ushering in images without cliché, and often so subtly that they escape thought or analysis. In fact, he includes a whole series of poems (“The Talking Tree Alphabet”) in which various species of tree are animated with words like “tongues” and “knuckles”. While luscious in its descriptions of colour and movement, “The Talking Tree Alphabet” quickly turns sorrowful when the trees become tangled in memory. Poems like “Oak” see a father “whispering goodnight” to his son. Here, Wyeth takes the symbol of a tree and stretches it to its most human – what it means to have ancestry, and what happens when these roots are severed by the loss of a parent.

The only poem in the collection to address grief directly is “The Flesh and the Spirit”, a brutal, graphic piece in which the father’s

convexed ribs poked through

the sheets, his sagging torso

a sack of rotten potatoes [.]

In this piece, Wyeth demonstrates his ability to transform; from abstract verses that float in and out of intellectual, semi-mystical territory, to sharp observations on the body. Further evidence of this is found in his lighter poems. He explores the strange humour of death and defies first impressions with a witty piece on Rovio Entertainment’s Angry Birds game. “Angry Birds” is as unexpected and perceptive as “The Flesh and the Spirit”, though they could not be further apart in tone.

There is a sense of care within every poem, a sense of rewrites and edits. Despite this, Wyeth will have us believe in moments of beauty – and he, a Romantic poet penning from inspiration while

black-licked

words fall like leaves littering the reflection

of the day, then are released birds.

Wyeth takes on a muse in “Aisling”, a pictorial poem ords move across the page in a slant to the right, mimicking the shape of a harp. This piece is wonderfully lyrical, striving to capture a young woman busking in rough winds. What “Aisling” shares with the rest of the collection is a fascination with nature, its capacity for interruption as well as for celebration – lines for any who enjoy the hidden wonders of the everyday.

The final part of the collection is challenging, and unlike anything in the preceding pages. “The Hedge” is a surreal, one-way exchange between a woman and a man. The man seems lost, and is very likely the same character in previous poems: the grieving son. His wife, a woman reeling from his absence, is unable to reach him, metaphorically as well as physically. Perhaps the message of “The Hedge” – indeed, “The Art of Dying” as a whole – is simply to journey on and let life grow out of death, as

a beautiful head growing out of a bough,

spreading its branches in all directions.

Leave a Reply