Nazhad and the Bell

Hiwa K

TRADE, Autumn Season @ Hospitalfield House (Westway, Arbroath, Angus);

until 16 Sept, Tue-Sat, 12-5pm

TRADE, Hospitalfield’s Autumn Contemporary Art Programme, brings a powerful 2-screen video projection work entitled Nazhad and the Bell by Kurdish-Iraqi artist Hiwa K to a Scottish audience for the first time. Installed within Arbroath’s historic Arts & Crafts property, this is a rare opportunity to view the project – originally commissioned and shown at the prestigious Arsenale venue during 2015 Venice Biennale – in a similarly historic context. Told in a deceptively simple, non-didactic manner, Nazhad and the Bell initially presents us with a moving story of transformation, alchemy and hope in the aftermath and wasteland of both the Iraq-Iran war (1980 – 88) and the two Gulf wars (1991, 2003).

TRADE, Hospitalfield’s Autumn Contemporary Art Programme, brings a powerful 2-screen video projection work entitled Nazhad and the Bell by Kurdish-Iraqi artist Hiwa K to a Scottish audience for the first time. Installed within Arbroath’s historic Arts & Crafts property, this is a rare opportunity to view the project – originally commissioned and shown at the prestigious Arsenale venue during 2015 Venice Biennale – in a similarly historic context. Told in a deceptively simple, non-didactic manner, Nazhad and the Bell initially presents us with a moving story of transformation, alchemy and hope in the aftermath and wasteland of both the Iraq-Iran war (1980 – 88) and the two Gulf wars (1991, 2003).

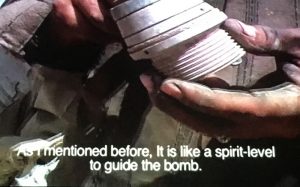

Shot mostly with hand-held cameras and over the course of 8 years, the installation’s left-hand screen introduces us to Nazhad, a Kurdish entrepreneur, whose childhood passion for melting metal developed through economic necessity into a lucrative business of deactivating and re-utilising valuable metal from mines, bullets, military planes and tanks. We witness the wealth of his knowledge of the materials and the weapons as he handles and describes – matter of factly – their differing elemental attributes, their employment of dangerous substances, and their countries of origin: the USA, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia and beyond. For an audience in the Western and developed world, it serves as an uncomfortable and timely reminder of our own complicity in the arms trade.

The right-hand screen of the installation relays concurrently the transformational aspect of Hiwa K’s project, as Nazhad’s military metal ingots are delivered, re-melted and cast into the form of a consecrated church bell by master craftsmen in an Italian metal foundry. History is now reversed, and a peace-keeping gesture is intimated by this action, as church bells were historically melted down in times of war to make cannons when bronze was limited. Yet, the materiality and method of K’s installation give rise to more subtle and complex contemporary issues and relations than the initial dichotomies of war and peace, sacred and profane, East and West may suggest.

There is a sheer physicality and intimate relationship between the body and the weight of the material as metal is handled, weighed, processed by both the Italian craftsmen and the Kurdish smelters. The camera lingers on the hands of the men, showing the poetry, skill and alchemy of the red orange molten metal as it poured by hand into moulds. There is no hierarchy between the two screens as smoke, steam, the roar of the furnaces, and the banging and clanging of the metal portray the ancient alchemical process of turning solid to liquid to solid form in Iraq, or in Italy. The space of translation of the spoken language of the Italian and Kurdish workers as they each describe their processes on top of one another, adds another layer of disjointedness to the complex, almost tangible soundscape.

There is a sheer physicality and intimate relationship between the body and the weight of the material as metal is handled, weighed, processed by both the Italian craftsmen and the Kurdish smelters. The camera lingers on the hands of the men, showing the poetry, skill and alchemy of the red orange molten metal as it poured by hand into moulds. There is no hierarchy between the two screens as smoke, steam, the roar of the furnaces, and the banging and clanging of the metal portray the ancient alchemical process of turning solid to liquid to solid form in Iraq, or in Italy. The space of translation of the spoken language of the Italian and Kurdish workers as they each describe their processes on top of one another, adds another layer of disjointedness to the complex, almost tangible soundscape.

The way we consume war in the West is often through a clean sanitised screen. Contemporary war is fought from a distance, witnessed by politicians thousands of miles from the front line. The viscerality, blood, and human contact are taken out of the equation. On slick graphic maps, distance, terrain, sand, dirt, sweat and miles covered are glossed over; targets, lines of conflict, movements and deployments of troops are represented by symbols.

Subtly and cleverly, without recourse to shock or graphic illustration, Hiwa K has reintroduced the substance, vitality and human ‘being’ back onto our screens. As we in the Global North become increasingly complacent and divorced from the manufacture and TRADE of goods with the Global South, Nazhad and the Bell highlights the importance of valuing materiality, not only in the arena of war but also in our everyday life.

Leave a Reply