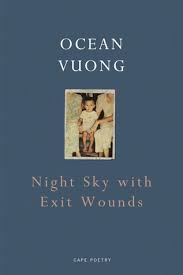

Night Sky with Exit Wounds (SHORTLISTED, 2017 TS ELIOT POETRY PRIZE; WINNER, 2017 FORWARD POETRY PRIZE FOR BEST DEBUT COLLECTION)

There is a tradition of photography that focuses on urban poverty, decay, disintegration, and entropy; in “urbex”, crumbling, abandoned buildings are transformed into hauntingly and fashionably beautiful images. I couldn’t help but bristle at the title of Ocean Vuong’s newly Forward Prize crowned and now TS Eliot Prize shorlister, Night Sky with Exit Wounds. Is Vuong’s work to be lauded precisely because of those landscapes of war and wounding metamorphosing into objets d’art in a reading culture keen to devour such artefacts? The book’s inside cover flaps, containing the requisite bio-textual stigmata emphasising the author’s refugee childhood, suggests such ramping up. Needless to say, these acts of consumption tell us more about ourselves than about the writer or work, as do, I suspect, my objections. What of the writing then?

There is a tradition of photography that focuses on urban poverty, decay, disintegration, and entropy; in “urbex”, crumbling, abandoned buildings are transformed into hauntingly and fashionably beautiful images. I couldn’t help but bristle at the title of Ocean Vuong’s newly Forward Prize crowned and now TS Eliot Prize shorlister, Night Sky with Exit Wounds. Is Vuong’s work to be lauded precisely because of those landscapes of war and wounding metamorphosing into objets d’art in a reading culture keen to devour such artefacts? The book’s inside cover flaps, containing the requisite bio-textual stigmata emphasising the author’s refugee childhood, suggests such ramping up. Needless to say, these acts of consumption tell us more about ourselves than about the writer or work, as do, I suspect, my objections. What of the writing then?

Night Sky with Exit Wounds begins with a startling image of a man being gunned down in a rainstorm. The poem’s contradictions – “not the man showering but the rain/falling through him”, an injured man whose singing fills the narrator “to the core/ like a skeleton” – and its powerful montage of arresting images – “guitar strings snapping”, ” a dark colt paused in downpour”, the “clutched breath” of the boy-narrator – suggest a zone of conflict marked by physical bodies as recipients of brutal violence. The minds that survive are equally traumatised, prompting the question: at what price? Responses are suggested, in this poem and others, by unrhymed fragments of free-verse, some in structured couplets, some in looser rangy sentences, run-on lines, and enforced white spaces to break sentence continuity. These strategies materialise a brokenness on the page, a stuttering of speech, a recurring nightmare. The obsessive temporal return to childhood throughout also signifies a circling around – trauma as unclaimed memory.

Reading Vuong’s depiction of war and their long term effects on the psyche is emotionally harrowing, but we should remember that these are his parents’ (or others’) experiences put on the page. The eye that writes is once-removed, the experience imaginatively reconstructed in words; the poems’ speaker repeatedly foregrounds words, letters and print: “The city so white it is ready for ink” or “A flash, a white/asterisk”, (“Aubade with Burning City”) or “Sometimes I feel like an ampersand” (“Immigrant Haibun”). Instead of reading Vuong’s collection as simply about as traumatised witnessing (as if that could in itself be simple), we should read it as a reflexive exploration of trauma in the writing of it. In that first poem, “Threshold”, lines such as, “I watched, through the keyhole”, “the cost of entering a song – was to lose/your way back” suggest this; that reflexivity makes for a more complex and richer book.

Just as Vuong’s love of fragments is counter-balanced in the collection by long pliant lines of poetic prose, the horror of killings is both leavened and heightened by familial intimacies; these provide the collection’s emotional centre. In lyric cadences, his “I” thinking and writing on the page, his hybrid seaguing real-surreal, and in his working with ‒ and out of ‒ the father-son bond, Vuong echoes Li-Young Lee’s work. Perhaps unsurprisingly, his “telemachy” uses the father-son relationship as the emotional and erotic matrix for all future relationships with men:

The face

not mine – but one I will wearto kiss all my lovers good-night:

the way I seal my father’s lipswith my own & begin

the faithful work of drowning. (“Telemachus”)

And while “The Gift”, a poem about his mother, should be cherished, love for men in all its glory is beautifully handled in Night Sky.

Not all of the poems work for me; some, like “Notebook fragments”, are just that. Yet there is also so much to admire. In a recent interview Vuong remarked, “I don’t have to have a stance [as a writer]. I just have to have questions, and I get to build a landscape where I get to explore them.” I’ve read the collection three times now, and each time there is more to engage with. In my book, that speaks volumes.

Leave a Reply