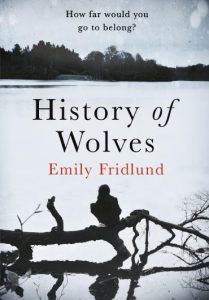

HISTORY OF WOLVES (SHORTLISTED FOR THE MAN BOOKER PRIZE 2017)

So runs the tagline to Emily Fridlund’s Booker shortlisted debut novel History of Wolves. It is suggestive of the latest pseudo-psychological thriller, but this does the book a disservice, belying a much subtler, somber work. The book is about a quiet desperation: yes, to belong; but also to come to terms with a world where any sense of belonging is fleeting.

Fourteen-year-old Linda lives with her parents in the backwoods of Northern Minnesota in the remnants of their former commune. Linda is the archetypal loner teen, at odds with her hockey and ice-skating obsessed peers. She struggles too for connection with her parents, whose idealistic dream with hippy comrades fell apart into bickering before the start of the novel. It is a clear metaphor for modern times: shared identity is all too elusive. Instead, Linda has nature: the woods, the lake, the family’s dogs, chained up outside their cabin. Other humans do find their way into Linda’s life. First, Mr. Grierson, the history teacher who encourages his pupil, but has a hidden shame. Then, the Gardners, a young mother, her husband and young son who have their own reasons for hiding away for the summer in the cabin across the lake.

The triumph of this book is the opening chapter. It is a thing of real beauty, and it is no surprise that in its original incarnation as a short story, it was awarded the 2013 McGinnis-Ritchie Award for fiction. Its descriptions of school life deal with character types familiar to us. There is something, however, about Fridlund’s descriptions that transcend these. For example, the reactions of the different groups of students to a teacher’s heart attack: “Boy Scouts” who trailed behind paramedics “like puppies, hoping for an assignment”, “the gifted and talented kids” who “reviewed symptoms in hysterical whispers” and Linda’s own memories of checking the teacher’s breathing, haunted by “a distant bonfire scent… some janitor getting rid of leaves and pumpkin rinds before the first big snow”. These set the tone for the rest of the novel, conjuring up a community, that, however dysfunctional, still breaks your heart if you are stuck on the outside of it. The chapter ends with an older Linda trying to track down her former teacher, to make sense of his secret as she tries to make sense of her past. If the rest doesn’t quite live up to the promise of the opening chapter, it is only because the bar is set high.

The fact that we know from the start that Linda’s attempts to achieve understanding are likely to fail doesn’t spoil the novel. The main plot line to do with the Gardners is still compelling, if a bit drawn out. From the first page, we know that as Linda’s life becomes entwined in theirs, she will be drawn, inexorably, towards a tragedy. When that tragedy strikes, it is all the more affecting for the knowledge that there were opportunities for it to be avoided. Even more powerful though, is the scene where Linda meets up with Patra, the young mother whom she has idealized, after everything that has happened.

Overall, some of the scenes from Linda’s 20s, as she struggles to leave behind her past, do feel a bit superfluous, and I was not wholly convinced by the ending, but what History of Wolves left me with, much more than its tragic story, was the sense of character and place, the sense of isolation. In an interview with Powells.com, (http://www.powells.com/post/interviews/powells-interview-emily-fridlund-author-of-history-of-wolves ) Fridlund has described how she tried to get at Linda’s emotional life, what her character is unable to say:

“through her physical experiences in the woods and being outside… [an] atmosphere as much as a concrete place.”

This oppressive mood is a potent extension of Linda’s voice and makes for a compelling narrative; together with the tremendous first chapter, more than enough reason to give this novel a read.

Leave a Reply