LINCOLN IN THE BARDO (WINNER, THE MAN BOOKER PRIZE 2017)

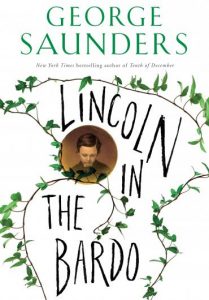

A Google search will inform curious readers that the word ‘’bardo’’ references an old Tibetan legend: souls making the transition from death to Nirvana, or, if they are less fortunate, to begin again in a new body, must first pass through the bardo. Think of it as a stopping station between different states of existence – or, for those who prefer something more tangible, imagine that frustrating no-man’s land between Chester and Wales. The front cover of my copy displays a despondent, sleepy-looking child staring down at the floor; the ‘’Lincoln’’ in question is in fact Willie Lincoln, the son of President Lincoln, who died at the age of twelve.

A Google search will inform curious readers that the word ‘’bardo’’ references an old Tibetan legend: souls making the transition from death to Nirvana, or, if they are less fortunate, to begin again in a new body, must first pass through the bardo. Think of it as a stopping station between different states of existence – or, for those who prefer something more tangible, imagine that frustrating no-man’s land between Chester and Wales. The front cover of my copy displays a despondent, sleepy-looking child staring down at the floor; the ‘’Lincoln’’ in question is in fact Willie Lincoln, the son of President Lincoln, who died at the age of twelve.

It is hard to know where to begin when explaining how this book is structured. Its most charming quirk is, at first, also its most vexing: the story is partly told by a trio of spirits that have remained in the bardo and partly by other spirits who interrupt this trio, and is given colour by swaths of quotations from various historical accounts of the Lincolns. We also occasionally hear from Willie Lincoln himself. For those unused to such a scattered approach to narrative, it could make for difficult reading.

We have Hans Vollman, who we learn has remained with a permanently erect ‘’member’’ in the afterlife, before he could consummate his marriage to a young lady, and Roger Bevins III, a young man ashamed of his preference for male company, who took his own life and immediately regretted doing so. This comical duo are normally accompanied by the Reverend Everly Thomas, a man who, because of an unfortunate experience, is convinced that he is destined for hell. The dialogue between these three men can be thought-provoking or gleefully silly, with Bevins and Vollman usually the mischievous upstarts and the Reverend the voice of reason. Saunders effortlessly weaves between themes of loss to conversations so preposterous that it is impossible to stifle your laughter.

This should be the part in which George Saunders is accused of tonal inconsistency, but in all honesty, those little buds of humour are a welcome break from some of the more sorrowful passages in this strange book: it’s a precarious balancing-act, but one that is performed masterfully: Hans Vollman: ‘When we are nearly arrived in the hospital-yard, young sir, and feel like weeping, what happens is, we tense up ever so slightly, and there is a mildly toxic feeling in the joints, and little things inside us burst. Sometimes we might poop a bit if we are fresh. Which is just what I did.’

The sadness of Lincolns junior and senior is poignant in the way that they feed from one another’s grief: Abraham Lincoln is unable to move on with his life, whereas Willie Lincoln struggles to move on from his life. The result is that both are bound to their melancholy. That Saunders is not afraid to question Lincoln’s commitment to his son – and, by extension, his long-held reputation as a ‘’good man’’ is testament to his ability as a storyteller. There is a chapter dedicated to the party held at the Lincolns’ residence on the night Willie died, and various sources give a somewhat damning account on the part of the President, who neglected his son in favour of merrymaking.

Why is this important? Because to err is human, and because the biggest of regrets are often reserved for the greatest of men and women. Abraham Lincoln would most likely not merely have felt sadness, but guilt too, and this knowledge arms the reader with a special kind of sympathy. By taking ‘’honest Abe’’ down from his towering pedestal and giving us a more convincing portrait of a troubled and flawed man, Saunders makes it possible for us to really feel the crippling loss of Willie Lincoln, not just as a character in a work of fiction, but as a real flesh-and-blood little boy.

Lincoln in the Bardo is a powerful and unique piece of writing by George Saunders. At times humorous and even crude, at times erudite, at times moving; it would make a fine addition to any bookshelf.

Leave a Reply