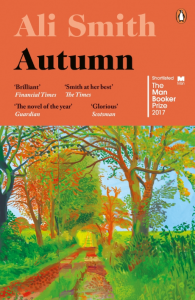

AUTUMN (Shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize 2017)

With Autumn, Ali Smith has written a work of such layered ingenuity that I’ve placed a bet on it to win the Booker. Smith, who has an enviable awards pedigree to her name – winner of the Whitbread, Baileys, Costa and Goldsmiths prizes and twice previously Booker-nominated, is one of those rare authors whose published work continues to surprise and excite with its form and creative expression.

With Autumn, Ali Smith has written a work of such layered ingenuity that I’ve placed a bet on it to win the Booker. Smith, who has an enviable awards pedigree to her name – winner of the Whitbread, Baileys, Costa and Goldsmiths prizes and twice previously Booker-nominated, is one of those rare authors whose published work continues to surprise and excite with its form and creative expression.

Autumn is ostensibly about the relationship between Elisabeth Demand, a thirty-two-year-old University Lecturer, and her neighbour and friend throughout childhood and beyond, Daniel Gluck, who is a hundred years old, and in the present time in a care home. Of course, this book is about much more than their relationship, and Smith manages to bring a variety of themes, and so much fine, nuanced writing into the dynamics of the interactions and inner thoughts of these two unlikely companions, that when I put the book down, I felt like I had read something akin to an epic, that crossed decades of history all in the modest space of 250 pages.

A third character, the non-fictional Pauline Boty, who was “Britain’s only female pop artist”, cements the already strong bond between the two main protagonists, as they discover their shared enthusiasm for both her provocative artworks and her invigorating and determined stance, despite great challenges in a supremely sexist society. Smith always does the mix of fiction and non-fiction so masterfully, and the way she seamlessly integrates the true history of Boty in Autumn is nothing short of breathtaking. The descriptions of her paintings are so easy to visualise that you almost don’t need to see the real thing:

The other picture was of a fleshy strip of images superimposed over a blue/green English landscape vista, complete with a little Palladian structure. Inside the superimposed strip were several images of part-naked women in lush and coquettish porn magazine poses. But at the centre of these coy poses was something unadulterated, pure and blatant, a woman’s naked body full-frontal, cut off at the head and knees.

Interspersed throughout the narrative are descriptions of Daniel’s dreams, his semi-conscious memories and the melding of both into a form of Magical Realism: “Then he pulls, straight out of his chest, his collarbone, like a magician, a free-floating mass of the colour orange”.

In other sections of the book, trees become a recurring, fantastical leitmotif, echoing the surreal feel of these dream sequences, and we are impressed by the enduring power of the natural world in contrast to the transitory nature of human life.

Other characters provide structure and support for the many themes explored: Elisabeth’s mother, from a generation of fifty-somethings, disillusioned with the political climate and adapting (or not) to a simultaneously more and less tolerant society, and Hannah Gluck (we guess that she is Daniel’s wife or sister), who, in a brief scene, stands as a reminder of the horrendous crimes of the Holocaust and its historical relevance in the current-day rise of the extreme right, and especially in the wake of the vote for the UK’s potential departure from the EU.

The author’s ability to always come at life and its complexities with a new perspective is both refreshing and rare. There is a section in Autumn which begins: “All across the country, there was misery and rejoicing.” In these three pages, Ali Smith has beautifully and creatively summed up the conflict and controversy created by the vote to leave the EU, what it means, how it feels, and, in all likelihood, how it will end. The next title in the quartet, Winter, is published on 02/11/17. I’ve never looked forward to the month of November quite so much.

Leave a Reply