Will I Ever Get to Minsk?

Jim C Wilson’s pamphlet, Will I Ever Get To Minsk? packs in poems in a variety of forms, from sonnet and cinquain to triolet and villanelle, and covering a range of material from ekphrastic poems, celebrations of writers, McCaig, Tranter and George Bruce, and poems about childhood experiences. There’s a wit and lightness of touch to many of the poems; however, an existential wistfulness infuses the pamphlet, carrying its concerns beyond the everyday. The opening poem, “Sunday school”, for example, ends:

Jim C Wilson’s pamphlet, Will I Ever Get To Minsk? packs in poems in a variety of forms, from sonnet and cinquain to triolet and villanelle, and covering a range of material from ekphrastic poems, celebrations of writers, McCaig, Tranter and George Bruce, and poems about childhood experiences. There’s a wit and lightness of touch to many of the poems; however, an existential wistfulness infuses the pamphlet, carrying its concerns beyond the everyday. The opening poem, “Sunday school”, for example, ends:

No fiery revelations; just cups of tea

and a Sunday expanse of wilderness.

The titles suggest straightforward descriptions yet they belie Wilson’s ability to convey the strangeness of the everyday. “What they did on their holiday” is a sensuous yet menacing glimpse into a couple’s relationship:

She cut a slice of soft goats’ cheese,

bit into its salty whiteness.

Let’s pay, he said, and chose an olive,

firm, and coloured like a bruise.

His use of form and, in particular, repetition and rhyme, is also used to great effect to convey a sense of threat. “R L S” (Robert Louis Stevenson) is a triolet:

The garden was unending to the child

but Mr Hyde was there, behind each tree.

A high bright sun smiled down; the breeze was mild;

the garden was unending. To the child

the trees were masts. He sailed across the wild

South Seas until he reached his final quay.

His Eden seemed unending; he was beguiled;

and Mr Hyde was there, behind each tree.

Largely regular in its triolet form, “R L S” employs iambic pentameter (an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable five times per line) with a phrase repeated in the first, fourth and seventh lines and another within the second and final lines. The poem also follows the triolet’s end-rhyme pattern. It’s a skilful use of the form to convey both the innocence of childhood as well as the sense of menace beneath the surface in only eight lines.

In the short poem, “East Neuk” the repetitions and end rhymes of the triolet form again serve to undercut the sombre message, this time in eight-syllable lines:

At Crail, Anstruther, Pittenweem,

the living’s lean, the boats are few.

Days are empty as empty creels

at Crail, Anstruther, Pittenweem.

A sighing’s in the grey-green sea

as men remember vanished crews.

At Crail, Anstruther, Pittenweem,

the living’s lean, the boats are few.

Just occasionally, the poetic voice is a little too knowing and self-aware. “In the Louvre” for example, opens:

Some call me Aphrodite, but that’s all

Greek to me. To friends, I’m simply Venus;

to be precise – de Milo.

“Adelaide at Sarenac” is an interesting poem about Adelaide Crapsey, inventor of the cinquain form. It starts prosaically enough:

With time to kill and winter near,

she created a new form of verse;

twenty-two syllables, five short lines.

It goes on to describe the form of the cinquain which begins and ends with two-syllable lines (“Two / brought the brief surprising end”). The poem’s ending is then both clever and poignant:

Was she convinced that little was more,

there, with that spondee, slow TB?

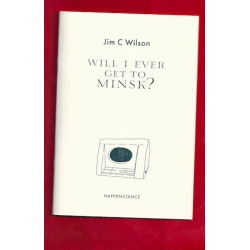

As ever, HappenStance has produced a high quality pamphlet with Gillian Rose’s simple yet very effective cover image of the old wireless:

which needs a dust. I peer at its dial,

wondering if I’ll ever get to Minsk.(“Stations”)

These are highly accessible poems – wistful and nostalgic, reminding us that we have our own Minsk, a place we may never reach.

Leave a Reply