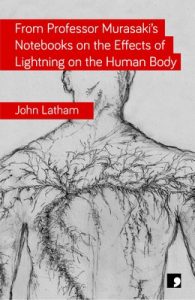

From Professor Murasaki’s Notebooks on the Effects of Lightning on the Human Body

This is John Latham’s sixth collection of poems; it is bold, bracing and comforting.

This is John Latham’s sixth collection of poems; it is bold, bracing and comforting.

Latham is an award-winning poet, an eminent physicist and a research scientist who has studied meteorology and cloud formation for over forty years. The title poem won second prize in the UK’s 2006 National Poetry competition and it offers the first hint that Latham is a poet who defies any assertion that science and poetry have no common ground.

When you’re writing poems, you’re often looking for links between things

and going into territory we don’t know much about. You’re looking for

shapes and indications. That’s also true of scientific research: you’re

searching for something that hasn’t been established before.

He observes the vagaries of life and science, as if he were observing the weather-patterns, with curiosity and an eye for detail. Poems about the weather have the cool, distilled language of scientific reports; one poem takes the form of a glossary. By contrast, his writing on the fears and delights of childhood is warm and intimate, written in short stanzas and free verse. Other poems are an eclectic mix of subjects. Creativity is explored in “The Artist is Not Satisfied” and there is an impassioned plea for humanity in “The President’s Tears”. In “On Not Reading Barchester Towers” an old man confined to bed finds comfort and companionship from the characters he has encountered through a lifetime love of literature:

For solace I smoke a pipe with Huck: we do not speak.

If I need a frank opinion I seek out Joe Gargery, who

unlaces his great boots to help him think. For wilderness,

abandonment, I send a carriage for Nastasya Filippovna.

Many poems explore the ravages of old age on the body and the mind. Latham does not spare the details on such a tough subject. He treats it sensitively and without sentimentality. We can’t control what happens in our later years, or the “storms” created, but we do have an influence on the way we reflect on old age. His poems offer a breathing space, a chance to discover new perspectives which may bring consolation.

In several of his poems memories are evoked in a seamless, dream-like way. His imagery, “purple silence stretched, thinned to violet” and “sleep-laced question”, seems to flit like clouds and linger in the memory for a long time after reading. Latham’s economic phrasing allows for some powerful emotional hits, like “lassoes” in the final line of “Rose-Blood.” This lasso is more than a length of rope with a slipknot at one end; it speaks of the complex emotional ties that tighten round our lives. It pulls us in and makes us pay attention to a poet whose work is uplifting and profound.

She’s resting now

but as I tiptoe to the door

a sleep-laced question

lassoes me, draws me back.

In “Adiabatic”, Latham journeys into new territory. Adiabatic is a thermodynamic term; simply put it describes a state in which no energy is transferred in or out of a system. At first sight, it is difficult to see how this can have any connection to the human condition. However, Latham offers us a delightful moment of revelation in the poem: it surprises and yet makes perfect sense. Latham’s poem has the serenity of a meditation, a sublime portrait of equanimity and contentedness.

I want no-one, nothing, only now. I curl

my shoulders inwards, round my heart

and all its heat, my temperature steady,

a new plateau. I am adiabatic, complete.

Latham keeps a weather eye on life, seeking out new connections and things not yet discovered. His poems glisten with new insights, both enthralling and consoling.

Leave a Reply