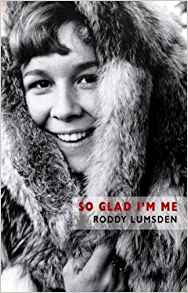

So Glad I’m Me (SHORTLISTED, 2017 T S ELIOT POETRY PRIZE)

Ten minutes ago, I wrote these words.

Ten minutes ago, I wrote these words.

Ten minutes; now I think I think them.

They knew me first, I fear, another me

went first and thought them.

Roddy Lumsden’s tenth collection, So Glad I’m Me, has a misleading title; in fact, one of the major themes of the collection questions the very nature of the self – what it means to be ‘me’, if ‘me’ means anything at all.

In the titular poem, the ‘me’ referenced is not Lumsden himself – rather, the quote ‘so glad I’m me’ was spoken by a female friend nodding off in the pub, inspiring Lumsden to write the poem (hence its opening line, ‘Clare is waning’). Even then, the poem appears to go on to question who Clare is with the word ‘me’; Lumsden lists ‘tragic heroines’ ranging from ‘Sandy Denny, post-recording’ and ‘Esther Greenwood roping in her thoughts’ to ‘gypsy girl from the Flake advert’. At first, comparing the ‘glad’ Clare to these women seems incongruous, that is until one considers that Lumsden is critiquing the concept of the tragic heroine – presenting Clare as seemingly ‘tragic’ yet content with herself.

The title poem reveals several recurring features in the collection: questions about our identities (for example, in relation to the roles – literary or otherwise – we play, like Clare the ‘tragedienne’); references to literature and music; and the inclusion of recurring characters, like Clare or ‘Amber Eyes’ – both of whom Lumsden has in an interview confirmed are real people – who give the collection a sense of structure, progression and authenticity.

Lumsden addresses troubling topics such the issue of identity, multiplicity and alienation from the self with wit. Take, for example, ‘Time Loop/Wishing Wells’:

…Don’t like

the other me, he has gained weight

and he likes Spiderman movies [.]

Other times, he allows the reader to feel the full existential weight of his reflections. In the poem ‘Cameron’ for instance, the persona recounts growing up near the Cameron reservoir – located near Lumsden’s hometown of St Andrew’s. He informs the reader of his ‘Scottish education’, remembering when such a phrase indicated ‘topological purity.’ The persona appears to find himself in his memories of his youth but the end of the poem throws this also into question:

It was barely a village and now I look it up.

It does not exist. I type my name, but pause.The vatic thermometer drops. I may not either.

Lumsden goes further than asking whether aspects of our past, like our education or the landscape of our youth, inform our identities. He considers how, if they do play a role, our identities may be changed not only because of personal growth, but because the places from our past change as well. Unable to find it online in the form that he remembers, the persona begins to doubt his memories of the village at Cameron that featured so heavily in his childhood, and by extension begins to doubt his own identity.

Lumsden is also clearly a fan of wordplay. He delights in playing with sound and rhythm– reflecting the fact that many of the poems discuss music. Consider ‘So Much Synth (Mix Tape, Slight Return)’, where the fast pace and internal rhyme of ‘chintz’ and ‘synth’ feel somewhat like a pop song:

hands at your own throat, knowing, soundtracked and shaking

that synth was not chintz but our own breath. That’s the truth.

This is only one example of Lumsden’s confidence with language and form. The entire collection is clearly the work of a craftsman pushing new boundaries in an exploration of our internal and external worlds.

Leave a Reply