Odes

[…] Dear wall,

dear gate, dear stile, dear Dutch door, not a

cat-flap nor a swinging door

but a one-time piñata. […]

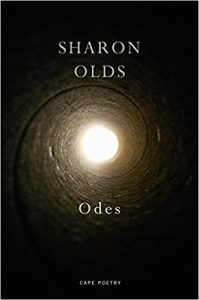

Entering any body of work via an “Ode to the Hymen” announces, with undeniable chutzpah, that things are about to change; really, there’s no going back. Sharon Olds’ most recent collection Odes is true to its opening promise of a heady read, which is not to say it delivers as the reader might expect.

Odes is indeed a body of praise poems, interconnecting the physical — both personal and universal — with autobiographical accounts. As with the extraordinary Stag’s Leap, Olds’ genius lies in her ability to write the deeply and often painfully personal with such insight, poetic skill, narrative drive and even wit that the needed larger connection is made. Stag’s Leap must have been difficult to follow; although Odes picks up some of its themes, it is very much its own creature.

That opening ode, directly preceding “Ode to the Clitoris”, fetes the “spherical trapdoor” (this from the “Second Ode to the Hymen”), but does not focus primarily on that organ’s centre stage moments (Don Paterson and others do that). Instead she considers it in utero, and there is something of the Matryoshka doll in her study. That image of inter-held female generations is recurrent and significant.

Odes is structured in seven parts; every poem a single stanza (of very varying length) address, each opulent with Olds’ characteristic word play, internal rhyme, sharply-severed breaks in almost conversational lines, ebullient rhythms and unsparing self-witness. For all her remorseless insight to her own aging, (“Ode to my Fat, Ode to Stretch Marks”, “Hip Replacement Ode”, “Ode of Withered Cleavage”), the generously whole soul apparent in Stag’s Leap is very much present.

Arguably, the titles which flare in the contents list do so because of their almost tabloid headline quality – Odes not only to the Hymen and Clitoris, but to the Condom, Tampon, Menstrual Blood, Vagina, Glans, and more. Perhaps “Blow Job Ode” does its best to out-headline the others, but the competition is fierce, from “O of multiple O’s” to “Ode to the Word Vulva”. Indeed it would be easy to make something of the gynaecological and sexual significance of that predominance and the strong editorial positions these poems enjoy. Easy, and glib. Famously, out of respect for her children’s feelings, Sharon Olds put aside Stag’s Leap, written in the wrench of her marital breakdown for fourteen years before presenting it for publication. Hardly the poet of instant or cheap gratification. So, the poems with the eye-popping titles are neither shy nor gratuitously graphic, but a reasoned, reasoning response and exploration of what it is perhaps to be Sharon Olds and also to be anywoman, maturing in the second decade of this century. There are shocking poems here, but not where you might first look.

White privilege is rightly scrutinised in 2017. In “Ode to my Whiteness”, Olds challenges her unwitting acceptance in a child’s skin. The next poem “Amaryllis Ode” (also from a child’s perspective), shocks yet more, being the first in an intermittent series examining her experience of maternal physical violence; the antecedents echo up her distaff line, and she charts her handover of that toxic legacy to her own daughter. That Matryoshka doll again. The lifetime of ripples affecting her relationship with her mother, right to her parent’s death, are amongst the most painfully wonderful poems here…being far more explosively groundbreaking than any lines about fellatio.

There are odes which play with the hemistich, with shape, odes including diagrammatic drawings (unquotable here), but it is where the long-separated Olds words her loneliness (consider the bitter-sweet brilliance of the black-humoured “Celibate’s Ode to Balls”), or explores an attempted new relationship through the physical, that she excels. Most especially, those harrowing poems detonating expectations of that mother-daughter relationship, and by extension questioning how women really interrelate, make this collection essential.

Leave a Reply