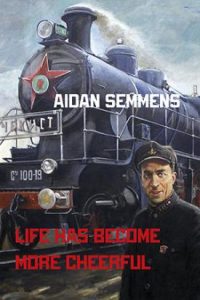

Life Has Become More Cheerful

This new collection of poetry, from Suffolk-based writer Semmens, takes as its title a quote from Joseph Stalin, dated 1938. The Soviet leader’s reflection, and the volume itself, look backwards over the “purges” – the waves of political assassinations and executions that were implemented twenty years after the Russian Revolution. This historical resonances of the collection’s title, colours Semmens’ poetry with a grim irony that feels worryingly apt for modern reader.

The volume opens with “1917” and the line, “this evening the atmosphere in the streets”, capturing the fervour and early optimism of the revolution. Specific references to the Kharkov Palace and the Nevsky Prospect conjure the moment of history and named individuals populate the streets as agents of the time. The poems then move forward through the early years of the Soviet Union, expressing a position that also shifts gradually, unearthing the brutal reality that came to be. The second half of Semmens’ revolutionary chapter gives us the stanza,

in a trial against conspirators

there is no need of proofs

historical context

confirms the charges[,]

with even more sour notes to follow. Two individual poems stand out: “From the Directory of 1936” ‒a four-page list of names, with occasional notes regarding their role in the Bolshevik movement or position within the communist government, and their deaths in 1937 ‒hits particularly hard. Later still we read “Say Some of Your Poems to Me Again, Comrade Poet”, which concludes Semmens’ own empathic journey from revolutionary avant-gardist to victim of the Gulag, or firing squad.

The Revolution, its centenary obviously bringing it to prominence, is not the only subject of the collection. Later chapters of poetry focus on more contemporary politics such as in “I Could Tell You But Then You Would Have to Be Destroyed” where we meet “a goatherd wearing / a Dick Cheney baseball cap”; other entries evoke scenes from a prison visiting room, or the violence of Israel’s inception which, of course, still continues today. Often, in these cases, the exposition feels personal, specific, and is consequently obscured from the reader. In the poem “Bleed”, Semmens writes “in this space/ a drop of poppy seed/ stands for the act of war” without naming the space, expanding on the imagery, or elaborating much at all. The meaning within these poems are evident, but hard for the reader to confidently grasp.

Fortunately, then, Semmens includes a means for edification within his personal take on the histories as he writes them. The final page of the book is a “Select Bibliography,” which contains many recently-written historical texts, but also Gogol, and Trotsky. Many of the poems are given epigraphs, sometimes quoting Walter Benjamin or Boris Pasternak, but often lifted from The Revelation of St. John.

Formally, the verse as written is consistent, and quite simple. Semmens mostly uses short lines, regular stanzas (of varying length, admittedly), and deceptively simple poetry. Lines are not firmly end-stopped; a poem’s syntax tends to run continuously, yet the breaks between lines seem precisely chosen, creating individual thoughts or images that rest distinct from one another:

chance allocates to Piatokov

the role of judge or villain

to be executed – someone

must be held accountable for catastrophes[.]

This form feels important to the kind of historical examination Semmens is working towards – reminding the reader that events always occur within context, supporting what comes before and after, but also of the significance of each individual step, the weight of a moment to be held.

Life Has Become More Cheerful, then, is not an easy read. The poetry can be glanced over, admired simply for the grim emotion of each entry in the collection, but there is more to the whole than any one poem can contain. This is an ambitious volume, which expects its reader to be shocked, provoked, and then to learn, both from the poet’s own words, and beyond.

Leave a Reply