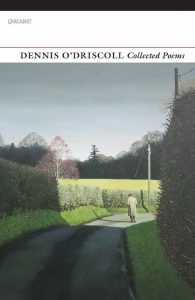

Collected Poems

Imagine the poet as a sandwich-board man, with his daily routine of spreading the word. Dennis O’Driscoll was such a poet – plain-speaking, astute, wary of ornament – his poetry pronounces ‘every day’ on the board at the front, and ‘death’ at the back, as he walks away. Born in Tipperary, on New Year’s Day in 1954, he died on Christmas Eve in 2012. O’Driscoll was a poetry critic, editor and scholar and, before his death, he had drawn up the plan for this volume of Collected Poems, which contains work from of his poetry collections, as well as new poems. O’Driscoll was well-known beyond the Irish poetry community. He reviewed for the London Review of Books, PN Review, Poetry Ireland Review and the Times Literary Supplement. His day job was working for Ireland’s Revenue and Customs Service.

Imagine the poet as a sandwich-board man, with his daily routine of spreading the word. Dennis O’Driscoll was such a poet – plain-speaking, astute, wary of ornament – his poetry pronounces ‘every day’ on the board at the front, and ‘death’ at the back, as he walks away. Born in Tipperary, on New Year’s Day in 1954, he died on Christmas Eve in 2012. O’Driscoll was a poetry critic, editor and scholar and, before his death, he had drawn up the plan for this volume of Collected Poems, which contains work from of his poetry collections, as well as new poems. O’Driscoll was well-known beyond the Irish poetry community. He reviewed for the London Review of Books, PN Review, Poetry Ireland Review and the Times Literary Supplement. His day job was working for Ireland’s Revenue and Customs Service.

O’Driscoll’s poetic attention was focused from the outset. His parents had died by the time he was 20 and he nurtured five younger siblings. Death is reliable and never far away –“someone today is seeing the world for the last time” (“Someone”). On his watch, titles of poems toll with significance “Serving Time”, “Residuary Estates”, “Long Story Short”, “Life Cycle” (a perfectly apt attribute to George Mackay Brown). He uses the logic and vocabulary of bureaucracy, and his wry observation of human ‘herd’ mentality to scrape poetry from the mundane, lifting it with dry wit and modest insight –

at what stage does the dying start

at what point do you decide

it is not worth renewing the subscription

that it will be up to your successors

to repair the bathroom lock

(“Undying”)

O’Driscoll’s poetry is recognisable for its characteristic economy, conversational tone, dead-pan humour, and rigorous policing against poetic decoration. He disapproved of obscure or oblique use of language. There is no myth or magical realism, little hope in anything other than the pan bread of here and now. For him, poetry has a moral duty be clear and honest. Christian motifs appear only to voice regret at absence of faith. He misses God – “ His grace is no longer called for /before meals” (“Missing God”). He bears witness to unfolding consumerism and the rise and fall of the Celtic Tiger in Ireland – “Deep-pile Celtic Tiger fur recycled/as a threadbare hair shirt.” (“2010s”).

We can read something of O’Driscoll’s writing practice:

Flicking through my notebook,

I come across ‘black butterflies

in the honeycomb heart of asters’.

Too grandiloquent, I think, too rich;

and, later in this notebook:

Then scraps in need of inspiration’s

heat to weld them into place:

‘there isn’t much glamour

in the breadman’s life.’

(“The Notebook Version”).

O’Driscoll’s approach to The Troubles was with gentle, non-partisan humanity – looking to other, especially Eastern European, poets for universality. He translates a poem by Wislawa Szymborska depicting moments before a bomb goes off, the terrorist watching from a safe distance (“The One Twenty Pub”). O’Driscoll updates the scene – a girl with a green ribbon is now a girl with an iPhone. This poem is all the more striking since it, too, adopts the viewpoint of an all-seeing outsider. The examples of the poetry of Szymborska, Czeslaw Milosz, Miroslav Holub, Zbigniew Herbert, were crucially important to O’Driscoll in his quest for honesty. They, in their direct use of language, gave him courage to write his own ‘anti-poetry’.

“No form, no poem” was O’Driscoll’s truism – “I love the way form and rhythm can somehow confer a higher destiny and density on even the most workaday words, equipping them to outperform their prose brethren….” Content and form were almost inseparable in his mind – and neither should be showy or obscure: “To rinse the world in rose water before you write is to bear false witness”. This is the challenge that O’Driscoll took on board – to face the workaday world we might have thought we’d risen above. He, and his discerning overview, are much missed. His Collected Poems are welcomed.

Leave a Reply