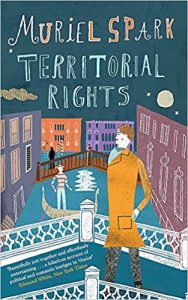

Territorial Rights

Coming a little later than halfway through Spark’s career, Territorial Rights is a romp. Set in Venice, the novel pulls together and twists half a dozen contrivances, and comes out with an almighty tangle. The plot begins with Robert Leaver, an English Art History student arriving in the Italian city, in pursuit of Lina Pancev, a Bulgarian defector who is investigating the murder of her father. Leaver himself is followed by art dealer Mark Curran and also by apparent coincidence, his own father, Arnold. Further elements are gradually added to the mix, and the true nature of the characters’ histories is left to bubble, somewhat odiously.

Coming a little later than halfway through Spark’s career, Territorial Rights is a romp. Set in Venice, the novel pulls together and twists half a dozen contrivances, and comes out with an almighty tangle. The plot begins with Robert Leaver, an English Art History student arriving in the Italian city, in pursuit of Lina Pancev, a Bulgarian defector who is investigating the murder of her father. Leaver himself is followed by art dealer Mark Curran and also by apparent coincidence, his own father, Arnold. Further elements are gradually added to the mix, and the true nature of the characters’ histories is left to bubble, somewhat odiously.

The mixture Spark creates is convoluted. The plot’s key players are at once entangled at yet utterly alienated from one another, creating a mesh of relationships buoyed up by tension and distrust. At times this is borne out through narrative focus, with the reader bearing witness to multiple conversations from which other characters are excluded, but there are moments in which it is made explicit. In one early encounter, Spark draws attention to the theme of subjectivity:

‘It was imported to replace a Venetian glass chandelier. We found it rather comical, amongst ourselves.’ And, as usual, Curran didn’t say who were ‘we’ and ‘ourselves’, thus leaving Robert far away from the scope of one of the many worlds that Curran pervaded and seemed to own.

These morsels of opacity carry on through the book, ending in a way that plays on the ignorance of its characters, keeping some of them utterly in the dark. This dramatic irony allows the audience a few cruel chuckles at the expense of innocent parties, as those holding more pieces of the puzzle direct those with fewer, nobody quite able to make a complete picture by themselves.

In terms of writing, Spark’s focus is very much on these characters. Several chapters unspool almost entirely as dialogue, and once the central cast has been developed these are easy to follow along, since the voices are crafted with habits and idiolect that mark them out as distinct and complete. Proceedings are mostly fluid, although there are odd turns of phrase (“‘Why Should I? If I choose to speak for us both, after all this time, I’ll do it.’”) which come across in reading as either slanted, or simply dated, nearly forty years after the novel’s publication.

Where there is description, much of it is pointed to the setting: Venice is a luscious backdrop to the drama, giving an air of class and romance to a plot which might otherwise be debauched or seedy. Characters find time to visit art galleries or discuss cuisine between snooping and slander, and the audience are allowed to take a tourist’s gaze of life on the canals. There is a moment in which Robert looks past his hotel garden and sees “tips of houses, bell-towers and a strange chimney pot”; other brief passages have conversations interrupted by waterborne funeral processions, or gaggles of American students at the Santa Maria Formosa. There is something of the Merchant Ivory charm to Spark’s novel, giving its readers a chance to wade through the private lives of its bourgeois ensemble, rummage through their secrets and make an exit without getting their hands dirty.

With a collection of murky, important and rather unlikable characters, Territorial Rights holds its own as a satire, with a plot that would not be out of place in a modern setting. The central themes of petty cruelty, secrecy and rejection are clear and consistent through the novel, and these personal conflicts are left unresolved with the story’s close. None of the characters we meet, and especially not the few with honest intentions, are left satisfied by the novel’s events, but instead are left with considerably more anxiety than they began. The novel feels juicy and depraved, and must have felt even more so when first written.

Leave a Reply