Scraps

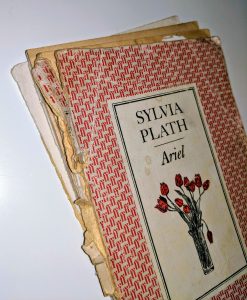

It’s my turn to present. Mrs Dover is in her usual position – lounging on a desk, elbows resting on her knees, hands clasped – she leans forward, ears primed for grammatical error. My arm shakes as I hold up my book. ‘This is one of my favourites,’ I utter, ‘Ariel, by Sylvia Plath’. Dover, as we call her, is smiling. ‘Why’d you not keep it in better condition then?’ I smile back. I was hoping she’d say that. My Ariel is split into two sections. Literally. It’s held together by an over-stretched hairband, and its  pages are yellowed – or more accurately, tanned, the colour of cardboard – and frayed. There are small tea stains on the cover, scattered like freckles on a face. I explain that it was already second-hand when my sister picked it up in a charity shop. I ‘borrowed’ it and it’s been mine ever since. It’s like a piece of me. ‘Alright’, Dover says, ‘but you’re more than the sum of your parts’.

pages are yellowed – or more accurately, tanned, the colour of cardboard – and frayed. There are small tea stains on the cover, scattered like freckles on a face. I explain that it was already second-hand when my sister picked it up in a charity shop. I ‘borrowed’ it and it’s been mine ever since. It’s like a piece of me. ‘Alright’, Dover says, ‘but you’re more than the sum of your parts’.

Its previous owner, a ‘Miss Butler’ as inscribed in red biro on the inner sleeve, has Tippexed over a word. I imagine this to be another name, one she chose to erase and replace with her own, perhaps someone she wished to forget. If I wanted to, I could do the same to Miss Butler, though I won’t. I want her to remain. Each scribble is a signature, a breath. In allowing her presence on the page, I keep her alive. This torn little book is not well-preserved, yet it does preserve something that fresh, unmarked copies cannot; something once removed from clean copies, perhaps twice removed from digital ones. Ariel is mine, but I can’t claim it. Its content belongs to Plath. Yet, in being battered and dog-eared, thumbed and annotated, it contains this vague something – something more than the words themselves. A soul, perhaps. Dover asks me how many times I’ve read it. Now I would say that it’s not a question of reading. If a book is simply read, then this is not a book. It is better to say that Ariel is a friend I’ve revisited often. Lines have been underscored and starred, syllables counted, metaphors unpacked. And so, with the help of Miss Butler and a mysterious ballpoint-owner, I’ve learned Ariel’s traits and habits. And I’ve loved her.

Ariel, then, is partly to blame for my paper hoarding. I cram shoeboxes with scraps ‒ teacher’s notes, photocopies, signatures, recipes, letters, receipts, posters, postcards and my most beloved: lists. I am told that my mum was a prolific list-writer. In the attic, I scan every piece of paper, searching for her handwriting. When I find her old shopping list, I kneel as if in prayer. It reads,

- Milk

- Sweetcorn

- Lavender oil

- Tissues

I expect it to resemble my own writing – words as I learned them, the dot-to-dot imitation of cartoon pencils: Swish and Flick! But it doesn’t. Her l’s are looped finely, like the eye of a needle. Her s’s are so hurried that they read like I’s. Between the lines, there is nothing of me. I focus on the words. Each item begins to carry the weight of a false moment:

Milk, she thinks, for Fraser’s coffee. Oh – and

Sweetcorn for Monday’s dinner, cod and parsley sauce. What else?

Lavender oil, to pop in the bath (she’s reading about aromatherapy) and

Tissues, a multipack – she feels a cold coming on.

I consider what she might have forgotten, what else she picked up in ASDA. Whether, like me, she usually left the shop with more biscuits than essentials. I wonder just how much this list reveals. Do I conjure her, or do I conjure an image of her – loving, thoughtful, tired? You may presume I have a passion for cooking when you see ‘aubergine’ on my shopping list, because only people I know who cook special dishes cook aubergine. You may also presume I am driven because I have written a list of goals. Perhaps I am a control freak because I write ‘To-Do’ lists daily, or because, if you could, you would see how I catalogue my CDs. You may presume, as I hold my mum’s tattered shopping list, that I am sentimental. It’s just paper, you might say.

All lists are sacred. They contain a kind of spell. Dover tells me that I should study English literature at university. It occurs to me that writing a list of tasks is willing them into being. Reading them, too. I know my mum’s list will not bring her back. Still, as I write out what I must accomplish to get to university, another sort of necromancy takes place. Self-belief, resurrected, heaves itself up from all that buried it, pushes through what others said, what they did; all my inadequacies – and in a column of lettering, live as hope. As with Ariel, I feel I must preserve this. I need it. Even when I no longer require it immediately, I can glance at my list and it will reflect me. It will reflect who I am, my successes and failures. Who I strive to become.

There are times, however, when destruction is just as necessary as preservation. Evanescence is blaring through my CD player and I am taking a pair of scissors to an expired library book: Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. I cut out Act V, scene III, somewhere around the hundredth line. Dover would not approve. Yet, I can’t help but know this to be an act of love. Romeo declares that Juliet is just as beautiful in death and I declare that these words are just so in their own deaths. I tear them away from the book and pull them into my own realm. I stick them on the wall above my bed. Mine is a possessive love. Narrow in my interpretations, I let my emotions read the work, and therefore I don’t fully comprehend Shakespeare’s layers of meaning, nor want to. I cut through their poetics, the systematic analysis. Simply, I have glimpsed something and it has become a part of me. Booklovers tend to place their most cherished volumes on the top shelf, in mint condition. An act of literal preservation and, I suppose, of selfless love. Or perhaps this might involve giving the book away, entrusting it to another. Soon my entire room is covered in scraps. What I love, what has become a part of me, surrounds me in one large collage.

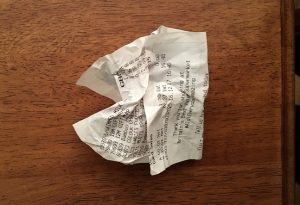

Collage is a form of recycling. Its power lies in its twofold ability to simultaneously make whole and  retain fragmentation. When collaging, I steal. In return, I give something back. I am participating in a creative exchange. Listing is a hopeful activity; I might becomes I will. The same is true of collaging. It is an exercise in possibility, and it doesn’t always demand glue. I smooth out a receipt, it reads –

retain fragmentation. When collaging, I steal. In return, I give something back. I am participating in a creative exchange. Listing is a hopeful activity; I might becomes I will. The same is true of collaging. It is an exercise in possibility, and it doesn’t always demand glue. I smooth out a receipt, it reads –

Loose Aubergines 0.264kg 0.48

Goats Cheese 1.50

ACE Vitamin Drink 0.99

Sweet Easy Peelers 1.29———————————————————

TOTAL 4.26

PLEASE RETAIN FOR YOUR RECORDS

My mind begins cutting away words, erasing numbers, adding phrases. I can choose to transform this into poetry –

There’s a 99 % chance

your words;

sweet, easy,

will loosen as you drink.I peel them from you

saying Please.

Still, there’s a 50/50 chance

you’ll say no

and 1 of us will walk away.

I bin the receipt as I enter my new flat. The walls are a stale magnolia. Suddenly, I am overwhelmed by everything which is not-me, all which is outside of me. I call this blank-canvas syndrome. I fear self-realised nothingness: undefined, unimpactful, no one in particular. I must impose or superimpose myself onto the world. Narcissism perhaps. I am no Buddhist; I cannot let go of the I. If you ask me who I am, I can show you in colour and text. I can play you a song. I cannot, however, tell you. My identity is dependent on scraps – and, like everyone, these scraps are the blocks that form me. In an odd sort of paradox, I cling to the leftovers of others – Miss Butler’s Ariel, my mum’s list, music posters, prints – to remind myself that I exist, and to forge something of myself. Something that says look. Here I am, the sum of my scraps.

Leave a Reply