Ever Dundas: An Interview

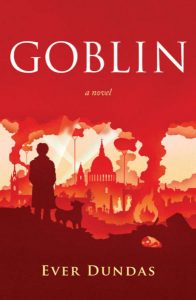

At the 2017 Dundee Literary Festival’s event for debut novelists, Ever Dundas is joined on stage by Gillian Best and Helen McClory. Dundas reads first, introducing her book Goblin. An hour later, she sits across from me in a small cafe area below the hall she has spoken in. There is a shift between the two spaces: the room downstairs is dark and cosy and we both feel more relaxed; actually able to talk rather than one listening to the other speak, without the need of the microphone that is still strapped to the side of her head. Moving from one situation to the other changes Dundas – going from an on display situation to something much more comfortable – yet there is no doubt that I am speaking to the same person.

Having read her novel, I feel as though I know something about the author behind it. There are biographical details I have gleaned from the acknowledgements: she has a husband who is listed under two names, Paul and Cinnamon; and, I suspect, two cats named Jabba and Belle, from the way she thanks them for “owning us”. She is a fan of Manic Street Preachers and Nietzsche. She has a soft spot for, as the acknowledgements call them, “freaks and goblins”, a love of Frankenstein and every skin-crawling body horror story written since. She is a vegan and passionate about animal rights. There is also a sense of personality that I can glean from the novel, seeing where the story goes and what the writer chooses to do. This is a person who is kind, gentle, yet uncomfortably familiar with violence and cruelty. Someone who is deeply interested in telling stories, passing on ideas and creating worlds. A writer knows what it is to imagine and to be captivated by the wonder of a story, or an image, or an object.

Goblin (both text and protagonist) began life, towards the end of Dundas’s Creative Writing MA, which she received from Edinburgh Napier University in 2011. The first 20,000 words were written during her time studying, with the full novel coming afterwards: Dundas uses the phrase “giving birth” when talking about the character’s inception; speaking as if she knows the person she has created, intimately. The decision to write from a child’s perspective was a crucial one, she says, because of her novel’s earliest inspiration: what spurred Goblin into life was an ambition to retell the story of the Second World War, and of the “pet massacre” of 1939.

The passage Dundas reads is not the same one in which her character witnesses the mass grave of household pets, euthanized in huge numbers at the outbreak of the conflict, but one set later. It centres on London’s destruction at the height of the Blitz, in which the heroine Goblin, aged eleven in 1941, is out to play. Her response to the presence of death and dead bodies is both horrific and adorably innocent: when adult characters’ attempts to convey the solemnity of the situation fall on deaf ears she herself is subjected to violence, and chased home. The child’s vulnerability, says Dundas, is crucial to understanding the issues she really wants to explore.

This is important to understanding her story: trauma, memory and storytelling obviously interest the author, and this moment in time encapsulated the matter for her. “We think we know World War II and how we feel about it,” she says later when I get to sit down with her, “but I don’t think we do.” In 2011, when the novel began to take shape, London was gripped by a different wave of urban destruction. The book switches its setting between past and present throughout, and Dundas’ framing of the Blitz against the riots of that summer is deliberate. She wanted to bring the reality of a violent landscape into reach of the reader: “I was walking through the streets of Edinburgh and I was thinking ‘what if all these buildings, these familiar buildings that I love were just suddenly razed?’”

Sitting downstairs, I get a stronger sense of Dundas as a person than I did watching the author on stage. She wears modest black clothes, decorated with bright details. The vibrant green eye on a chain around her neck matches the colouring in her fringe. On her lapel is a brooch in the shape of a phrenologist’s bust; it has the words “here be monsters” inscribed above the lines that carve up the scalp. I feel as though Ever is someone who has spent her life following her own sense of style, and would be proud to find herself in the company of the “freaks and goblins” she writes about. At the literary festival, the panel’s chairperson describes all three novels as having a “difficult central character”, and this is certainly the case with Goblin.

In front of an audience, Ever had sat with a certain stiffness, which seems to dissolve here faced with nothing but myself and a cup of green tea. I ask about events like this and how she finds them: “I was really anxious. It’s not my cup of tea at all,” she explains; but then follows it up with “I’m actually getting a lot more chilled about it.” It seems that what has helped the most is that people have come to her, sending invitations to her directly. “I’m not going to say no,” comes out as the conclusive motivation, but this has to be done off her own back rather than a publisher seeking out spots for her to promote her book.

In fact, Dundas’ publisher has given much less support than she had hoped – Freight Books’ co-founder,  Adrian Searle, left the company in April, just before Goblin was published, leaving a number of authors in hot water. “There’s been a lot of uncertainty,” says Dundas, mindful of it being a touchy subject. The author picks her words carefully here; I can sense her frustration from across the table, but a glow of optimism forces its way through: “Goblin has had good reviews, it continues to be available in bookshops, and it has just been shortlisted for the Saltire First Book Award.” The rights to the novel have reverted to her and she is looking, with her agent, for a new publisher to keep the book in print. She has a lot to feel optimistic about. “I knew I was going to be in this for the long term,” she says, “I’ve wanted to be an author from the age of seven. I’m going to be ninety and still sending out manuscripts, I don’t care how long it takes me.” With a little more thought, Dundas even admits that she “loved every minute” of the Wigtown Book Festival, and has another event on the 15th of November at the Scottish Parliament, focusing on imprisoned writers as well as reading some of her own work. Although, this might be the last event on her calendar for a while. After all, she says, what she’s supposed to be doing is “writing”.

Adrian Searle, left the company in April, just before Goblin was published, leaving a number of authors in hot water. “There’s been a lot of uncertainty,” says Dundas, mindful of it being a touchy subject. The author picks her words carefully here; I can sense her frustration from across the table, but a glow of optimism forces its way through: “Goblin has had good reviews, it continues to be available in bookshops, and it has just been shortlisted for the Saltire First Book Award.” The rights to the novel have reverted to her and she is looking, with her agent, for a new publisher to keep the book in print. She has a lot to feel optimistic about. “I knew I was going to be in this for the long term,” she says, “I’ve wanted to be an author from the age of seven. I’m going to be ninety and still sending out manuscripts, I don’t care how long it takes me.” With a little more thought, Dundas even admits that she “loved every minute” of the Wigtown Book Festival, and has another event on the 15th of November at the Scottish Parliament, focusing on imprisoned writers as well as reading some of her own work. Although, this might be the last event on her calendar for a while. After all, she says, what she’s supposed to be doing is “writing”.

At the panel someone asks the inevitable question: “what are you working on now?” There is a hush as though this might be rude, bringing up the dreaded second novel; Dundas answers clearly and without reservation. Her next novel, she reveals, will be titled HellSans. She describes it as a Science Fiction Thriller, using a ubiquitous font which is pleasing to most and anathematic to a ghettoised minority, as “a thinly veiled metaphor” for capitalism and disability. She teases out other elements, including familiar-like cyborg creatures that might bear some resemblance to Goblin’s Monsta, but also the sewn-together nature of the older Frankenstein’s Monster, which certainly blends horror and science fiction. Switching from what is ostensibly historical fiction to dystopic sci-fi might be quite a shift, but Dundas doesn’t want to be hemmed in by genre. For starters, it carries the risk of “ghettoising” the author, but often it’s just not the best way to understand a piece of work. Goblin’s marketing describes it as “Ian McEwan’s Atonement meets Guillermo Del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth”, which is a combination I would never have put together until reading Goblin. Dundas says the comparison came from her publisher, but has given her a lot to live up to: “I think it works. Atonement and Pan’s Labyrinth weren’t really direct influences but they were in the back of my head. I knew of them and I knew the similarities so I think it’s quite a nice shortcut.” She certainly agrees that if it makes people want to read her work, then that’s a good thing.

Dundas is certainly not alone in being an author unafraid to switch genres. The panellists list a few with Ever naming Margaret Atwood and Michel Faber, as examples. Later, throughout our main conversation, and in the chit-chat either side of it, Dundas raves about authors whom she admires; film-makers whose work she loves. Between us we manage to bring up William Gibson, Denis Villeneuve, Ted Chiang, Brian Aldis, Peter Jackson, John Scalzi, Mary Shelley and Darren Aronofsky, enthusing about them or picking them apart, in equal measure. Mutual favourites include China Mieville and Terry Gilliam, the latter’s film Tideland being a particular influence to Dundas – she confesses to having chased Gilliam onto a train, having missed him at an event, to have her copy of the DVD signed. Even then, this feels like a tiny list: as I look over a shelf of books on sale between the hall in which she has spoken and the cafe we will sit down in, Dundas comments on those she has read, recommending (although “it’s not perfect”) a book on transhumanism and cybernetics that I hadn’t seen before. For all her nervousness about being on stage, when Dundas gets onto a subject she cares about it is obvious, she speaks about it with a passionate, erudite authority.

Her writing, too, gives a clear indication of her drives and fixations. Goblin’s plot manages to span seventy years, half of Europe, a swerving narrative voice and still hammers a whole row of nails in terms of thematic exploration. With its focal point being on the “pet massacre”, the novel looks closely at the relationship between humans and animals, but also at history and storytelling, memory and repression from trauma, injury and disability. Dundas confirms these matters need more work, and all those fascinations will get more attention in her writing. “Those huge things are in HellSans so even though I say I’m going on a different direction genre-wise, and it might seem quite an extreme turn, it’s got very similar themes.” Those interests are given an abject, visceral treatment, and Dundas’ writing returns often to the physical feeling behind her ideas. A few days after our conversation, emails me again, sending me another short piece of writing titled Choke, which centres on her experience of having an endoscopy. Reading it is horrific, written, as it is, from her own first-person perspective; Dundas relates her tale to that of prisoners being force-fed, or animals in labs, extending the affect she has created. “We control their bodies,” she writes in the email, bringing up that kind terror and using it to shine a light where she wants us to look.

That kind of physical horror is central to Dundas’ writing, it seems. “I’ve always been kinda morbid,” she admits, “there’s definitely something that fascinates me with the body and flesh.” I wonder how this intersects with her other themes – how to square morbid curiousity against her veganism, and how she has progressed from one to the other. “A lot of people think animal-rights people are saps,” she explains, “and they can’t face the real horrors of the world, but I think actually we’re the people who are facing the horrors of the world – we’re not really the sentimental ones, we’re the ones that face it head on I think.” I ask whether there is an intersection, then, between body horror and a passion for animal rights. “Yeah, there’s definitely a connection there.” She thinks about other works that delve into that brutal treatment of their characters’ flesh, and how that relates to our treatment of other species. She cites Michel Faber’s Under The Skin as having “strong” parallels, whether intentional or not; then goes on to bring up Oliver Cronk and Jacqueline Traide’s 2012 performance art piece, in which Traide was caged, force-fed, and tortured in a Regent Street shop window. “When I was a kid I would look at horrendous bloody pictures of what we’ve done to animals, whereas these days I just don’t look at that any more. I get on and do my animal rights thing and be vegan but I can’t cope with that any more.” Dundas does not seem righteous, or condemnatory in her criticism at what is happening, but appalled at the suffering that she knows is being carried out, and firm in her belief that things will change; that they are changing.

The intensity of the subject spurs a rush of thoughts, and Dundas jumps from point to point with amazing rapidity yet without any loss of clarity. Will there be more “in terms of the story of Goblin”? She answers, “that’s finished, that’s done.” Appropriately, we circle back to the origin of Goblin as our conversation draws to a close: the “pet massacre”, and the burning of London. Even in 2017, London is still on fire. Were the book written now, might it have featured the Grenfell Tower fire as its present-day anchor point? “I suppose I was just trying to collapse time a bit by having that symbolism, and trying to draw people back into World War Two, and reassess it. Because the pet massacre makes you look at it differently anyway.”

Ever Dundas’ writing is, similarly, clear and direct, through all its disparate moments. With only one novel to her name it is hard to say, but this might be a writer who excels in her versatility. She is an author who writes in many directions, shifting and perhaps returning to old ground at times, but one who follows a single path in all her work.

Leave a Reply