Unfixed

When you are a child born in one place and raised in another, ‘home’ is complicated. Even more so, when ‘home’ is a series of couches, hotel rooms, borrowed apartments, and rented houses. ‘Home’ is something that belongs to your mother, gifted to you through pictures and stories, the folklore of her youth. It is someplace distant, with vague cousins and impossible snow.

I have only pieces. Moments.

There are, of course, the stories. Do you remember…

do I remember?

Having had so many bedrooms, living rooms and kitchens, a room that is my own, that is home, is difficult to imagine. There was only ever ours, not yours or mine, and nothing was permanent. We shared, always. Except when we didn’t. Beds and chairs, drawers and cupboards, even wall space changed hands, or was lost in the small gambles of children.

Memories like water on glass –

time and touch, rivulets

pooling on ledges, flowing

nothing to hold them.

Unfixed.

There are images, things I can almost grasp, but they’re slippery. Red tile, fire ants, bloody toes, lobster bath, painted tortoise, cocktail umbrellas, roof whirligig, stolen rhubarb, blue eyeshadow, bottled bees, secret cupboard, tree swing, garage roof. Sometimes they stream together, spurred by unexpected sensations. Sometimes, there’s a clarity, a sureness that doesn’t come from what I’ve been told. That comes from me.

There are stories of course, banded about like trophies – ‘Do you remember when Sara broke her collar bone again? I remember when the chimney caught fire’. There’s an expectation of reward, some participation in the telling, a smile, a laugh, a small contribution to the tale. You do remember, but you remember it differently – that’s not how it happened – something’s forgotten.

A shrug, the half-smile and short shake of the head –

My history, my home,

an apologetic gesture.

I remember how the story is supposed to go. I remember which points are contentious. I know who tells the story best. I know them by heart. But I don’t remember. My roots are shallow. I am not tied to this place or that. An exile nation of six, displaced over and over. Things were lost in the moves – possessions, pets, people. Our shared identity bound by the losses small and large, the happiness and the hurt that moved with us, by a language, half-spoken and half-understood.

I am not what my mother expected, had hoped for. She wanted our relationship to be different from the one she had with her parents, wanted it to be nourishing, fulfilling. But in the same way that she cannot escape the way she was raised, neither can I.

![]()

I knew a trans girl named Suzi. When she chose her name, she wanted it to be Siouxsie, but she allowed herself to be convinced that a more traditional spelling would be better. She was a ‘moquette’, she could tell you the identifier numbers and operational history of every bus in the city. I asked her once, if she ever considered becoming a driver, if she ever wanted to have control of the machine, to be part of the service she followed so meticulously. She told me she would never wear a shirt and tie again.

When I started my current job, my friends were certain that I would struggle with the uniform. That the shirt (which was pale blue at the time), and the little silver badge would niggle at me until I tore them off. I told them that I welcomed the uniform. That, after the intensity of my last job with disadvantaged children, which would linger at the edges of my mind every night, I wanted to be able to switch off from work as easily as peeling off a pale blue shirt at the end of the day. They didn’t believe me. It wasn’t the uniform that I would rail against, but what it represented, they said. It wasn’t the shirt or the badge but the binding to brand and service. As if the little piece of plastic had some talismanic power, and by allowing the letters of my name to be pressed into its silver coating I would be giving-up something of myself.

When I started my current job, my friends were certain that I would struggle with the uniform. That the shirt (which was pale blue at the time), and the little silver badge would niggle at me until I tore them off. I told them that I welcomed the uniform. That, after the intensity of my last job with disadvantaged children, which would linger at the edges of my mind every night, I wanted to be able to switch off from work as easily as peeling off a pale blue shirt at the end of the day. They didn’t believe me. It wasn’t the uniform that I would rail against, but what it represented, they said. It wasn’t the shirt or the badge but the binding to brand and service. As if the little piece of plastic had some talismanic power, and by allowing the letters of my name to be pressed into its silver coating I would be giving-up something of myself.

Anne peers at the lettering on her hospital wrist band, but she doesn’t recognise it. She knows she’s in a ward, she knows her own name, she knows it will be printed on the perforated plastic, but she sees only little black squiggles now. However hard she stares the letters refuse to coalesce into any kind of meaning. The effortless way her eyes used to travel along a line of script and call forth the entire span of her knowledge for each word. The knowledge of sound and shape, and crucially, how meaning could be changed, nudged in a different direction by simply nestling one letter amongst a particular set of other letters, had … gone. There are many things that she’s lost that frighten her, but this most of all.

Things are given names and labels for ease of identification. To facilitate an imparting of knowledge that is both rich and efficient, these labels often contain some nugget of the truth of the item and/or some measure of its value. ‘Slut’ and ‘bitch’ are useful labels that inform of both the sex of the subject, and deviation from some social convention. The essence of the descriptors can be demonstrated by using them to replace the word ‘woman’ in a sentence: “that woman at the bar” becomes “that slut at the bar”, efficiently conveying insight into the character of the subject.

Someone told me today that they identify as a bisexual, demigirl, tomboy/femme. When I asked what a demigirl was, she told me it was someone who only partially considered themselves a girl. I asked if I should change the pronouns that I used to refer to her. No, then yes. I should use the plural, or per (they read that in a book). I asked if they were only partially a girl, then what was the other (non-girl) part. I wanted to raise the point that if they were partially a girl then they were also partially a boy and so the label was arbitrary, but I didn’t want to fall into the trap of the masc/femme binary argument, and to be honest, I didn’t want to look ill-informed. They told me they weren’t sure, but they were most certainly mostly a girl. They felt freed by this new label. Able to abandon the stressful performance of being a woman, leave behind their skirts and dresses, and not care about other people’s babies. They were so grateful that the expanding vocabulary of the LGBTQIA+ community could offer them a label that gives them a sense of place and permission to escape the pressures of feminine norms. I asked them if the feminine and masculine norms were eliminated, if the pressures to perform in specific ways were gone, did they think that they would still require their demigirl label? Yes. You need to know who you are in this world after all.

My sister is a Reilly, so am I. We bear it with an odd mix of pride, shame and resentment. Being a Reilly comes with responsibilities – you must be intelligent, educated, successful in a field that is impressive but provides a public service. You must be derisive of anyone who is not as selfless as you. Drug abuse is scorned, being an alcoholic is understandable given the stress of your job. Marriage and children are expected – being gay is only acceptable if you are exceeding all other expectations.

Your world is different from mine, I think. It must be. You give it reign over you, let it take you somewhere shaded and do whatever it wants. What’s it like to step off a cliff like that? To push past your sense of self-preservation as you lean out. Push through the jolt of panic, rush of adrenaline, until you’re falling, falling. Pushing through the air, you feel the pressure of all those bunched up molecules pressing against your body. You don’t flail, your arms are out, embracing. You wanted this. What’s that like?

My mother’s friend died last year. I visited her before she died, I read to her and felt the crush of her fingers when a streak of pain crossed her abdomen. She told me she was waiting – “It’s just a waiting game now”, she said. And I knew that she wasn’t waiting for the chemo to starve the cancer in her belly, or the radiation to destroy the growing tissue, she was waiting to die.

We never talked about her dying, only her illness. The medications, the sickness, the tingling in her hands from nerve damage that she would likely have for the rest of her life. That’s how it went, little facts nestled among the big fiction of her survival. We pretended that the rest of her life was as it had always been, an infinite stretch of days and years, and not just the weight of hour after painful hour. She asked my mother to ask me to visit, to bring books and music. I went informed, knowing that she was in pain, that her loved ones weren’t coping, that they had been difficult. I went knowing that I was to be a distraction, an uncomplicated waste of her diminishing time.

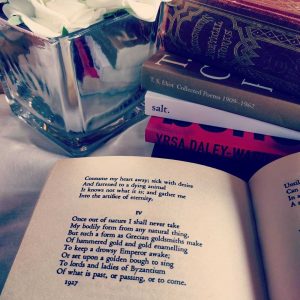

One day, she asked me to read poetry, to give her a crash course. She’d never liked poetry – “too much pressure to find the hidden meanings”, she said. I laughed and brought her Wordsworth, Tennyson and Donne. She wanted more, something that she could feel, something that spoke to her. I brought Whitman and Dickinson, but there was too much death in one and too much life in the other. I tried Yeats, “Sailing to Byzantium”. She read it again and again. It was the most energetic she’d been in days. It frightened me a little. I’d heard that some people have bursts of life right before they go, like flashing into the darkness. I was alone with her, didn’t want the burden of her last minutes, didn’t want to be left with the image of her flashing eyes poring over the line ‘fastened to a dying animal’. Didn’t want to think about what it meant. She asked me what I thought it was about – “being old”, I said. She said she felt old. She felt tired and small and slow. I could feel the platitudes creeping over my tongue, but I smothered them. Forty-eight isn’t old, but it’s as old as she was going to get. She was elderly, a fading crone at the very edge of her lifespan. I asked her what she thought it was about – “trying to find the hidden meaning”, she said.

One day, she asked me to read poetry, to give her a crash course. She’d never liked poetry – “too much pressure to find the hidden meanings”, she said. I laughed and brought her Wordsworth, Tennyson and Donne. She wanted more, something that she could feel, something that spoke to her. I brought Whitman and Dickinson, but there was too much death in one and too much life in the other. I tried Yeats, “Sailing to Byzantium”. She read it again and again. It was the most energetic she’d been in days. It frightened me a little. I’d heard that some people have bursts of life right before they go, like flashing into the darkness. I was alone with her, didn’t want the burden of her last minutes, didn’t want to be left with the image of her flashing eyes poring over the line ‘fastened to a dying animal’. Didn’t want to think about what it meant. She asked me what I thought it was about – “being old”, I said. She said she felt old. She felt tired and small and slow. I could feel the platitudes creeping over my tongue, but I smothered them. Forty-eight isn’t old, but it’s as old as she was going to get. She was elderly, a fading crone at the very edge of her lifespan. I asked her what she thought it was about – “trying to find the hidden meaning”, she said.

Sometimes I feel as if I came into being one chill afternoon on a hill covered with pale green meadow grass. This is my first clear memory. This is the only one that I know is mine alone. The only one that no one knows but me.

It makes me think of my mother. I don’t know how I came to be on that hill, what had prompted me to leave school and roam until I came into consciousness. I don’t know who I was in those months and years before my mind became my own. My mother remembers. She knows about every time I was happy or sad or sick. I was often sick and rarely happy. A sickly, grumpy child. I had a propensity for wandering off, easily distracted, insatiably curious. She knows the names and shapes of my favourite things. My first dog, my favourite song, the title of the books I read over and over. She keeps this me with her and gives her to me if I ask.

But only if I ask.

Leave a Reply