Life in Motion: Egon Schiele/Francesca Woodman

The rationale behind exhibiting the Austrian artist Egon Schiele (1890 – 1918) with the American photographer Francesca Woodman (1958 – 1981) is, to quote Tate Liverpool, that they are “sublimely innovative artists that connect across time and medium.”

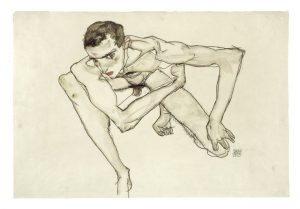

Wandering through the gallery there’s an immediate sense of kindred spirits, in the ease with which the eye moves between alternating rooms displaying Schiele’s cadaverous-like images on blank backgrounds executed with feverish sharp lines, and Woodman’s often ethereal-like blurred black and white images. Similarities abound; they were experimental, energetic and prolific in their work, both approached the naked human form in a frank, matter of fact way, and they frequently used their own bodies as the subject matter of their images. A sense of practical workmanship pervades both artists, when Woodman was asked why she modeled herself, she stated, “It’s a matter of convenience. I’m always available.” Woodman’s images are not the only specters, the exhibition is haunted by the tragedy that both artists died young. Schiele died aged 28 from Spanish flu, and Woodman took her own life aged 22.

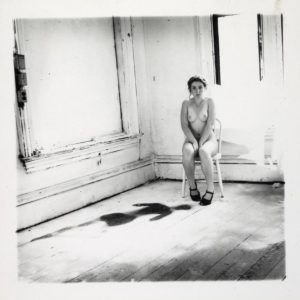

In Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island 1976, Woodman is nude and seated in a bare room. A little distance in front of her is the shadow of her body, but its not the shadow of a seated person, it’s in the shape of a person lying prone on the floor. The photograph was created by scattering photosensitive powder on the floor to create a ‘shadowgraph.’ In the light the powder turns white, and in the dark it turns black. At first sight, the shadow might represent Woodman’s physical life tied to the earth, yet the way in which it is detached from the body, and seems to have its own identity and shape, is reminiscent of Peter Pan’s shadow. The photograph left me questioning whether Woodman was consciously evoking some of the dark symbolism of Peter Pan’s shadow. Was she, like Peter Pan distressed by the detachment of her body and shadow?

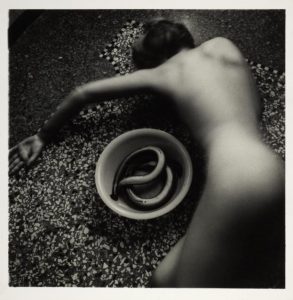

Woodman frequently used long exposures in her photographs creating blurred images, depicting our bodily presence as fleeting, otherworldly even. The ‘Angel Series’ of photographs (1972 – 1977), portrays shadowy figures, which melt into their surroundings, and almost disappear into thin air before our eyes. Other photographs like the Eel Series, Venice 1978 depict clearly defined sensuous images; Woodman lies curled up beside a bowl of eels, and the curves of her body mirror the curves of the eels.

Schiele’s images of the naked body are intimate and unapologetic, but at the time he strongly rebuffed suggestions that his work was pornographic, stating “Are there no artists who have done erotic pictures?” A quick scan of faces in the gallery revealed that his images still retain the power to shock and challenge a modern day audience.

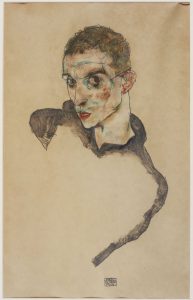

Some paintings, like Self-Portrait 1914 are tinged with a green-grey hue, the colour of the thin layer of corrosion that tarnishes some metals. In the same way as tarnish bestows character and maturity to objects, it also makes them appear unsightly and tainted, and in the same way there is a dark edge to many of Schiele’s paintings which is difficult to define. Despite depicting adults engaged in pleasure seeking acts, Schiele’s face and the faces of his models, often stare out from the paintings with detached, even distasteful expressions, as if they are not personally involved in the subject matter, and have no emotional connection to it.

Some have criticized Tate Liverpool for displaying two such important artists together, suggesting they merit individual exhibitions. Although separated by many decades, the synchronization between the two is undeniable. Schiele’s images rock the senses, Woodman’s images entice and soothe, and together their images of the naked human form are enthralling, unforgettable and not to be missed.

Wow! This is great Jane. Sounds like an amazing experience! Thank you.