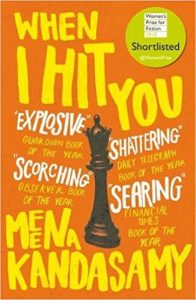

WHEN I HIT YOU

This must be one of the most shocking novels of 2017. In it, the author recounts the ordeal of a violent and abusive marriage. Shortlisted for the Jhalak Prize 2018 and the Women’s Prize for Fiction 2018, longlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize 2018, it has also been nominated as Book of the Year by the Daily Telegraph, The Observer, The Financial Times and The Guardian.

This must be one of the most shocking novels of 2017. In it, the author recounts the ordeal of a violent and abusive marriage. Shortlisted for the Jhalak Prize 2018 and the Women’s Prize for Fiction 2018, longlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize 2018, it has also been nominated as Book of the Year by the Daily Telegraph, The Observer, The Financial Times and The Guardian.

Meena Kandasamy is an Indian novelist, poet and feminist activist who lives in Chennai and London. Her first novel, The Gypsy Goddess, published in 2014, was nominated for the Dylan Thomas Prize and her poetry collections have received much critical acclaim. Nothing prepares you for this novel. I read it in one evening, unable to tear myself away from the sense of claustrophobic horror that Kandasamy invokes, as her marriage to a seemingly respectable college professor descends into a struggle for survival.

The newlyweds settle in Mangalore, a city far from the narrator’s family and friends. She tells her story in the first-person, giving terrifying accounts of how her husband – a self-proclaimed Marxist activist – effectively cuts her off from the outside world by using extreme emotional blackmail to force her off social media, taking away her phone, demanding her email passwords, forbidding unrestricted internet access. These actions not only prevent her from communicating with supportive friends, they destroy her ability to continue working as a writer. He justifies all of these abuses, by taking a disingenuous stance as a Communist to ‘educate’ her out of being what he calls a ‘petit-bourgeois prostitute’

My husband decides to set me free. Free of my past. Free of the burden of memory. Free of the burden of lost dreams. In setting me free, he says, he is setting himself free. He deletes the 25, 600 –odd emails from my Gmail inbox. All at one go. Then, to prevent me from writing to the Gmail help team and having my emails restored, he changes the password to something I do not know and cannot guess. He erases everything on my hard disk.

Despite being repeatedly beaten and raped over a period of four months, it is her writer’s mind that somehow helps her to endure the terror of her husband’s physical, emotional and sexual brutality. She doesn’t in fact present an endlessly graphic account of the violence; rather she is, in her mind and in the narrative, ‘writing back’ to the abuse. That is the novel’s power and its uniqueness. It is endlessly creative, imaginative and experimental. She cites influences from Roland Barthes and Guy Debord, to Italo Calvino and to the poets Sandra Cisneros, Maggie Nelson and Anne Carson.

In an interview with the online magazine, Wire, Kandasamy acknowledges that the novel is based on her own experience. But she states in the same interview that she decided to write it in a reaction to the awful statistic that 37% of Indian women experience domestic violence or sexual abuse. She felt a powerful need to address this in her writing. In her own words, she describes the way that she wanted to write this novel:

I have learnt that what is left unsaid speaks louder than anything that is put down into words. The texture of the novel hints and refers and theorises the violence, but never does it revel in it. I remember writing in my diary how I was going to write this novel [ ] how do I want to write rape and violence? I think part of the aim of such horror is to punish, but it is also to disgrace the woman. And I wrote down, I will write in a way in which I am not disgraced. I will write in the same way in which I lived through all of this: carrying myself with enormous, infinite grace.

Leave a Reply