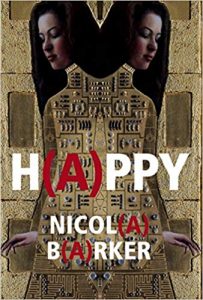

H(A)PPY

Barker’s twelfth novel is a wonderfully unusual phantasmagoria of narrative and typography. It takes place in a future which has been rebuilt after the “Floods and the Fires and the Plagues and the Death Cults”; where ambition, ego, desire, death and poverty no longer exist. This calm, sustainable new world is inhabited by “The Young” who claim, “We are innocent. We are Clean and Unencumbered.” Their thoughts and emotions are displayed publicly on “The Information Stream,” and each person is represented by a “Graph” and monitored by a “Sensor.”

Barker’s twelfth novel is a wonderfully unusual phantasmagoria of narrative and typography. It takes place in a future which has been rebuilt after the “Floods and the Fires and the Plagues and the Death Cults”; where ambition, ego, desire, death and poverty no longer exist. This calm, sustainable new world is inhabited by “The Young” who claim, “We are innocent. We are Clean and Unencumbered.” Their thoughts and emotions are displayed publicly on “The Information Stream,” and each person is represented by a “Graph” and monitored by a “Sensor.”

As part of this perfected society, our musician protagonist Mira A should be happy. But instead, she is “h(A)ppy.” “Why? Why does the A persist on disambiguating? On parenthesising?”, Mira A asks. The glitching of this word is our first clue that she is not fully synonymous with the system. She has a “kink.” This glitching intensifies as the novel progresses, paralleled by a movement from standard narrative form to wild typographic showcases, until the whole thing explodes. True, this tightly controlled dystopian future and a protagonist who screams rebellion resonates with several sci-fi narratives – from Orwell’s 1984 to Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror. However, H(a)ppy severs these ties fairly quickly. Its boldness allows the novel to smash its own path into unknown territories of genre and form. Barker uses a kaleidoscope of font colours and sizes; pages of text which repeat a single sentence; embedded symbols; mathematical equations; bars of music; sentences which spiral down the page to create pattern and image. . .the list goes on. She takes us on an erratic journey, which explores words and all they hold – danger, emotion, power and duplicity.

The novel is interested in how information interacts with consciousness. Mira A becomes obsessed with telling her own story, an illicit enterprise. Barker says in The Guardian that: “The thing you’re reading is the thing that’s not permitted. So the words themselves are a breach of something, the telling of the story is what’s wrong, and the urge to tell it is what continues.” In a world where ego and excessive emotion are forbidden, Mira A explains, “I am…we…we are…we are tormented by the narrative.” She must find ways around the system. She admits: “I transform the lucid dreams into music. So I am composing. And I find that I can compose, if I am very careful, without affecting the graph too dramatically.”

So, with the help of dreams and music, Mira A enters a “dark forest of words,” causing the turbulent discourses of her inner self to be laid out on the page in realistic disarray. The building of a “Cathedral” allegorises the creation of her inner narrative. However, this is pervaded by a second story surrounding real-life guitarist and composer Agustín Barrios. This is a dark, fragmented tale of Paraguayan myth and music which provides a stark contrast to the main plot. A little digging reveals that Agustín Barrios himself wrote a guitar composition called “La Catedral”, famous for its complexity and range of movements. The parallels do not stop at the title – if H(a)ppy were a piece of music (which it almost reads as in parts) then it would sound exactly like the haunting “La Catedral.”

The myriad of forms, narratives, and typographical experimentation Barker employs result in a novel which is undeniably engaging, innovative – and often difficult to follow. It is chaotic. It is confusing. It is difficult to quote or analyse. It is open to wildly subjective interpretation. It is a novel which Barker herself admits, “gets nuts.” Which is perhaps quite brilliant considering H(a)ppy is, ultimately, a satire of the crazy age of information we are living within.

Leave a Reply