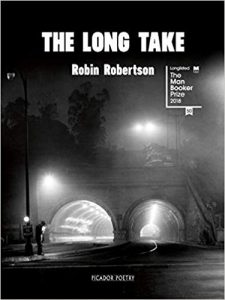

THE LONG TAKE (or A Way to Lose More Slowly)

For some, Robin Robertson’s book-length narrative poem is “unclassifiable”. Shortlisted for awards invariably dominated by prose, it is epic in both scale and ambition. Resisting the strict fit of epic form, its protagonist (the aptly-named Walker) is overly human for deification; its netherworld trips, earthly hells. Remembered paradises are also worldly. For those neither employed as librarian or bookseller, is this defiance of categorisation problematic? Clearly, Robertson himself poet, translator, creative collaborator and editor is untroubled.

Anyone familiar with Robertson’s poetry may be unsurprised by this move towards filmic noir. His work often has echoes of the sepulchre, and his reader will wait over a hundred pages before Walker smiles. Briefly. Necessarily, this tale requires a larger landmass than the poet’s north-eastern Scotland, but the threads of Nova Scotia are pulled from an older Scotland. The epigraph (quoted above), motto of The North Nova Scotia Highlanders, translates as “Our footsteps will not allow us to go backwards.” The regiment’s particular fate on Juno Beach, and their motto’s painful truth for Walker, propel The Long Take towards its inevitably unhappy fulfilment: “American cities have no past, no history. Sometimes I think the only American history is on film”.

Composed in four sections, named only as “1946”, “1947”, “1951” and “1953”, followed by “Credits”, this beautifully-designed book’s alignment with cinematography is sharply focused. Structurally, the poetic delivery, typography, and stanzaic patterning is integral to the cinematic experience. Similarly, Robertson’s use of black and white photographs must surely be deemed heuristic rather than merely cosmetic. The Long Take offers the possibly expected poetic attention to detail in every line, but the overall structure is equally verse-specific:

The map of the city unfolded as they drove, and every day, at every light or stop-sign he was noting down what he saw

Consider the map of “Downtown Los Angeles (1948-58)”, rightly neither endpapered, nor directly affixed to sections set in that city. The criss-crossing of the street plan not only supports the narrative, but there’s a recurring metaphor, warping and wefting throughout, and an almost self-referencing fascination with the constructed, particularly the gridded, slatted and bolted; constructions and constrictions, set against the more fluid drifting of people. This tight weave becomes ever more throttling as the story advances: “a run of slates slithering down, the snicker of rifles”.

There’s a relentlessness in the wording, but also in how the narrative wires pull, tightening the inescapable horror around ex-soldier Walker, and the increasingly visceral nature of his PSD. Poetry books are rarely page-turners, but Robertson achieves that, in tandem with a poetic efficiency which demands close reading: “The morning light blades into the room”

Detailed minutiae, the personal, set against the vastness of geographical, historical and human scale, percolate through cinematic images. Zooming perspectives are set out from the first section onwards. The repeated symbolism of the demolition site’s wrecking ball comes ever closer as the conclusion looms:

[…] sewer pipes,

working overtime to fill the sea with Kotex,

straggling there like jellyfish,

or glazing the beaches with condoms[…]

These are lines which deliver the kind of fittingly contemporary environmental hit from a historical text that Annie Proulx surely craved in Barkskins. Native American oppression is referenced, but poetry’s flexibility, its terse and taut linguistic and structural adventurousness, pierces in a way that that a much longer prose tome could not. Late on, we hear the prescient “Yeah-yeah-yeah” of gunfire, and may recognise Joni Mitchell’s imagery, giving qualities outliving the poem’s time-frame. If every word in poetry has to earn its place thrice, that’s well demonstrated here:

There was a blur of neon as he fell,

headlong, into his own shadow,

The Long Take may, or may not, win prizes, but its inclusion on these lists should bring poetry to a wider readership. Historians, fans of movies, of Americana and more will be hooked. But Robertson’s audience is wider still. Superb.

This is a work – however it may be classified – that will stay with the reader who has walked its pages, spent time with it, imagined, responded, paused, returned to it again and again.