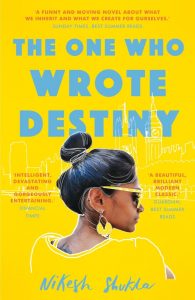

THE ONE WHO WROTE DESTINY

Following the success of his 2016 crowdfunded anthology The Good Immigrant, Nikesh Shukla returns with his latest novel. The One Who Wrote Destiny features some of the issues surrounding race in the UK that were the basis of The Good Immigrant but offers a whole lot more. It is a story about family, loss, and life, illuminated by poetic spirituality.

Following the success of his 2016 crowdfunded anthology The Good Immigrant, Nikesh Shukla returns with his latest novel. The One Who Wrote Destiny features some of the issues surrounding race in the UK that were the basis of The Good Immigrant but offers a whole lot more. It is a story about family, loss, and life, illuminated by poetic spirituality.

The One Who Wrote Destiny follows three generations of the Gujarati Jani family whose story begins and ends in Kenya. The novel reads like a collection of short stories with each character’s story given its own space, whilst not being isolated from the others. The novel starts with Mukesh’s story, as he moves from Kenya to Keighley and falls in love with Nisha. This story sets up Shukla’s varied style throughout the rest of the book. The opening gives a taste of the writer’s humour, narrative skills and at times poetic style. Written in first-person, Mukesh tells the reader of his experience of moving to England in the late 60s. Through the protagonist’s voice, Shukla writes in a charming and infectious way as if the reader and Mukesh were friends. The use of words like ‘yaar’ meaning ‘mate’ and other Gujarati phrases creates an intimacy between the narrator and reader and affirms that the listener of the story is someone like Mukesh. It is later revealed that the tale is being told to one of his children. Behind the charm and humour of Mukesh’s story, Shukla captures the treatment of immigrants in England at the time in a direct and simple way. The contrast in tone from light to dark shows how brutal these experiences were: ‘Paki-bashing. I’ve heard whispers. Stories’.

The next section of the novel is set in modern-day London and follows Mukesh’s daughter Neha’s story. It provides an intimate character study with its close first-person narrative in the present tense. The reader discovers that Neha suffers from the same terminal illness that her mother had. The most captivating part of this section is how Shukla gives the reader access to Neha’s emotionless and logical mind. Some of the deeper recurring themes emerge in this story as Neha navigates her way through the idea of destiny in a methodical manner. Neha’s cold nature and her frayed relationship with her father does not make for a likeable protagonist, but as her condition worsens, the journey we take with Neha becomes emotionally hard-hitting. The reader’s closeness to Neha amplifies her loneliness and makes sympathy for her almost inevitable.

The vividness of characters and emotional depth that runs through Destiny is less impactful in Rakesh’s story. His account loses the intimacy found in the first two sections. The tone and function of this section seem to shift and become less personal and focus more on issues of diversity and Rakesh’s place as an artist of colour. Shukla creates distance by showing Rakesh, a stand-up comedian, from other people’s perspectives. The novel digresses from its intimate qualities and takes a moment to discuss the roles and responsibilities artists of colour face in the UK: ‘You don’t need to be the voice of all the brown people any more. There’s enough of them around now that you don’t represent all of us’. While Rakesh’s story is still linked to the others, this portion of the novel is notably different from the rest and sees the writer deviate a little from his central themes of loss and destiny.

To say that Destiny’s core themes are loss and destiny is a simplification: Shukla packs in a multitude of themes, issues, and narratives. It is both the novel’s strength and its one drawback. On the one hand the novel lends itself to re-reading, but on the other it can result in the text losing focus at points. What remains consistent is the power and directness of Shukla’s writing.

Leave a Reply