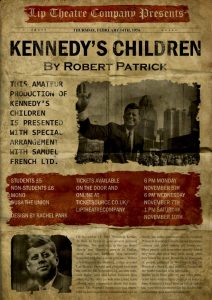

Kennedy’s Children

Kennedy’s Children, by Robert Patrick opens in a New York bar. The year is 1975. The month, February, is the one usually considered the most depressing all over the northern hemisphere. The day is St Valentine’s Day. Six lonely characters inhabit the set, including the barkeep. The play tracks the lives of five archetypal Americans in their disillusionment after the heady years of the 1960’s floundered into the doldrums of the ‘70’s. The characters never acknowledge one another but speak directly to the audience. Only the barkeep stands in silent recognition of their words, an anchor in a room of untethered egos.

Kennedy’s Children, by Robert Patrick opens in a New York bar. The year is 1975. The month, February, is the one usually considered the most depressing all over the northern hemisphere. The day is St Valentine’s Day. Six lonely characters inhabit the set, including the barkeep. The play tracks the lives of five archetypal Americans in their disillusionment after the heady years of the 1960’s floundered into the doldrums of the ‘70’s. The characters never acknowledge one another but speak directly to the audience. Only the barkeep stands in silent recognition of their words, an anchor in a room of untethered egos.

It’s not surprising that these five people are floating in a Sartre-like limbo ‒ with so many icons of hope assassinated (JFK, in particular); with the protesters of the ‘60’s having lost their fire; with the spark and originality of experimental theatre dimmed by commercialism; with the tragedy of so many broken men returning from the chaotic madhouse of Vietnam; and, even, with the hole left for some by Marilyn Monroe’s death.

Kennedy’s Children is a modern version of an early Renaissance Morality Play. In the early part of the play, the characters seem to be cut-out dolls, types, if you will. If you are willing to watch as they slowly reveal their histories and characters, you will be rewarded with several powerful monologues.

Each member of the cast brings enthusiasm and freshness to the characters. On the night I attended, tempo was lagging a little at the beginning of the first Act, but towards the end, the players found their rhythm. During the second act, they were not just enjoyable to listen to, but broke the barrier separating actor and character, at times. Director Eimear McNamara cast the roles well and impressed me with her ability to very competently fill the shoes of a cast member who had fallen ill.

The ensemble is, as mentioned, a group of enthusiastic amateurs who display their skills with professional aplomb. It would be unfair to the reader to tip him or her off to look for any particular instances of brilliance as each character makes his or her mark in surprising ways during the course of the performance. Their interpretation of the script is responsible for the success of this play.

The production venue of the Mono works well as the set for this play, having easy access to tables and chairs from the DUSA cafés. It also has a rather shambolic atmosphere with barstools and booths scattered with the odd empty glass, which suits the play. Although the performance was delayed slightly by a technical difficulty (someone had removed lights from the set prior to the Company’s arrival that evening, I was told,) it proceeded with professionalism. Lighting was well thought out, each character being washed with colours indicating their inner psyches. However, as some of the lights had been removed, I’m not sure we got the full effect. I was told the set was dimmer than it should have been, but this also worked well, for me, given the overall tone of the play.

Kennedy’s Children provides us with a reminder of how, sometimes, our better natures fail us due to circumstances beyond our control. Each of Kennedy’s archetypal lost children, however, did win their dreams in some small degree over the intervening years. We have come some way toward the better world the ‘60’s tried to engender, but with events as they are falling out worldwide now, this play is relevant and watch-worthy. In this way, it may serve as a beacon of hope for things to come.

Leave a Reply