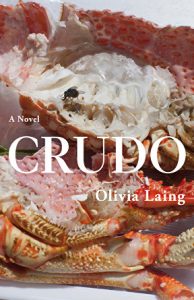

CRUDO

Crudo, Olivia Laing’s first novel, is performance. Laing dons the mask of radical, experimentalist Kathy Acker, in a performance of experimental writing, and in text, her main character Kathy tries to resolve her commitment issues through the performance of marriage. Laing, a non-fiction writer, steps into the guise of Acker to bring a manic and ironic perspective to the events of her life and the world during the seven weeks leading up to Laing’s wedding. In an interview for The Paris Review, Laing said, ‘I needed a perspective that wasn’t me, a character that could observe the turbulence in an exaggerated, frenetic, paranoid way.’ Acker’s own style of writing was to ‘borrow’, to lift whole works and reshape them by playing within them. By ‘borrowing’ Acker herself, Laing pays homage to the writer while also telegraphing her intent to be provocative and subversive.

Crudo, Olivia Laing’s first novel, is performance. Laing dons the mask of radical, experimentalist Kathy Acker, in a performance of experimental writing, and in text, her main character Kathy tries to resolve her commitment issues through the performance of marriage. Laing, a non-fiction writer, steps into the guise of Acker to bring a manic and ironic perspective to the events of her life and the world during the seven weeks leading up to Laing’s wedding. In an interview for The Paris Review, Laing said, ‘I needed a perspective that wasn’t me, a character that could observe the turbulence in an exaggerated, frenetic, paranoid way.’ Acker’s own style of writing was to ‘borrow’, to lift whole works and reshape them by playing within them. By ‘borrowing’ Acker herself, Laing pays homage to the writer while also telegraphing her intent to be provocative and subversive.

In the first line, Laing establishes that the narrator and Kathy are the one and the same: ‘Kathy, by which I mean I, was getting married. Kathy, by which I mean I, had just got off a plane from New York.’ This is the only paragraph where Kathy and Laing exist separately, for the rest of the novel Laing refers to Kathy in the third person. I found it bizarre, knowing that another reader, ignorant of how the book was written, would be reading a completely different novel. It reads at a feverish pace and I’d find myself stopping to guess at the origin of a line, or Google it, knowing full well that someone else would just read on and enjoy the droll panic. Laing wrote the novel in seven weeks; she began to write while sitting a sun lounger in Italy, exactly as the second paragraph depicts. The novel is almost a diary, ‘a raw day-by-day’ from the moment Laing picks up her pen. She’s confirmed that all of the biographical elements of the book are true, either for herself or for Acker: the trouble is sorting them out (there is a cheat sheet at the end, where Laing cites her ‘borrowings’).

Being Kathy Acker works two-fold for the novel, it gives Laing a degree of distance from her own experiences and allows her to be ‘exaggerated and ironic and playful and viciously self-lacerating,’ but it also allows her to be blunt and crude and savagely sexual. Most of the time, I could separate the more mundane aspects of the novel into the ‘Laing’ column, and the more extreme events into the ‘Acker’ column. It wasn’t always so easy though; the Kathy voice is either deeply sardonic or on the edge of hysteria, and the borrowed Acker quotes slip into the diction and sentiment so easily that it’s clear to see why Laing chose Acker as her avatar.

Crudo is as much about Kathy’s coming to terms with her changing life, as it is about Kathy living in a changing world. It is deeply affected by the political upheaval in the UK and the US. Laing comments on the early events of Trump’s administration and frames her own instability within the unexpected and inexplicable events before her wedding: ‘Everyone talked about politics all the time but no one knew what was happening’; Kathy talks about her wedding all the time but doesn’t know what it will mean.

Kathy’s unmooring is dealt with in the same manner as the world has been reacting to Trump era politics, a sort of shocked inevitability. While this generates a few highly amusing situations, it also leaves a watery taste of bitter disappointment in the mouth: ‘it was all the same thing, it was the world talking. You couldn’t hate it, or you did but that was just more of the same, another opinionated little voice in an indecently augment chorus.’

Leave a Reply