EUROPA (Shortlisted, TS Eliot Prize)

‘You Are Now Entering Europa’, the opening poem in this, Sean O’Brien’s ninth collection, derives its title from a Lars von Trier film. In the film prologue, the voice of Max von Sydow primes the listener, ‘On the count of 1 to 10, you will be in Europa’, and as he descends the numbers, we are drawn into a monochrome, nightmarish Europa: ‘Be there at 10… I say 10…’ O’Brien’s poetry on the page shares something of the sonorous authority of that hypnotist narrator. The reader is not being led into their happy haven of wellbeing, but into a place where time is a force to be reckoned with and nothing is as solid as it might seem. In O’Brien’s poem, it is the grass that progresses to obliterate us, inevitably and without delay, in a countdown that puts us all in our place. His work might sustain the poet, but it is

‘You Are Now Entering Europa’, the opening poem in this, Sean O’Brien’s ninth collection, derives its title from a Lars von Trier film. In the film prologue, the voice of Max von Sydow primes the listener, ‘On the count of 1 to 10, you will be in Europa’, and as he descends the numbers, we are drawn into a monochrome, nightmarish Europa: ‘Be there at 10… I say 10…’ O’Brien’s poetry on the page shares something of the sonorous authority of that hypnotist narrator. The reader is not being led into their happy haven of wellbeing, but into a place where time is a force to be reckoned with and nothing is as solid as it might seem. In O’Brien’s poem, it is the grass that progresses to obliterate us, inevitably and without delay, in a countdown that puts us all in our place. His work might sustain the poet, but it is

So near to its conclusion now

That I will never finish it. The grass

Is at the door, is on the stairsIs in the room, my mouth, is me […]

(‘You Are Now Entering Europa’)

Although the collection title might lead to expectations of Brexit-oppressed poetry, O’Brien’s remit is wider, constituted by a collective imagination. He suggests that Europe can neither be defined, nor left, since history and the present are intertwined. The feeling of Europa that he conjures is one shaped by conflict, exile, and a long chain of possession:

Old, unhappy, far-off things

Domesticated hereAs fictions to be real in.

How did it come to be

So thoroughly possessed, this land,

(‘Dead Ground’).

O’Brien’s metrical poetry takes the reader on something of a melancholic ghost train ride; the scenes and motifs are reminiscent of Grimm’s fairytales or Dickensian London, where a nineteenth century link-boy raises a dark flame:

England’s necropolis conquers the ocean

And drains it: the world is this island

Concealed in the fog of triumph.

All bow at the name of Great Death.

(‘Link-Boy’)

Even so, the old songs of self and home continue to beguile us. Admirers of O’Brien’s poetry will know that he offers plenty of dark humour to offset the descent downwards and that going deeper and deeper will lead to the recognition of the uncanny, both known and unknown:

What is this if not more of the same,

When the merciless ghosts insist

That if I dare listen, I’ll hear my name?

(‘One Way or Another’).

O’Brien is poetry’s consummate skilled technician. The metre is the poetry’s scaffolding, for example from ‘In the Event’,

Time slows. What must happen makes ready.

Time now to avert the gaze,

Attending not to great affairs,

The falling of kings, the death of states,But to the interest of the mind, the heart,

In what is called imagination. Now

Before it is forbidden

I take up my book…

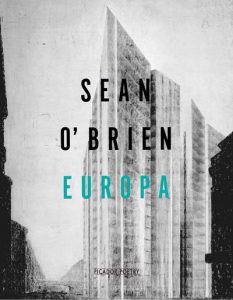

The interplay of rhythm and meaning is exquisite. I hear, highlighted in the default metre, the word ‘Imagination’ which could be given six syllables to scan iambic. This word will sustain this weight of attention in this poem and in the book as a whole. O’Brien reminds us that imagination and reality are as inseparable as history and the present. To enter Europa, is to realise that ultimately you must leave, since neither you nor I, the poet nor the place, will withstand time’s inexorable countdown. To where would escape lead, but deeper and deeper? There is a gentle irony implied in the delicate cover image of a crystal skyscraper, designed by Mies van der Rohe for Friedrichstrasse in Berlin, yet never built, rising higher and higher.

Leave a Reply