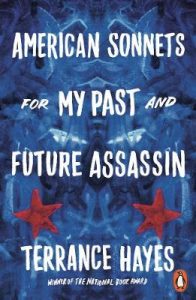

American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin (Shortlisted, TS Eliot Poetry Prize)

American poet Terrance Hayes’ latest poetry collection, American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin, is a series of sonnets that, as the back of the paperback declares, ‘traces the fault lines of race, gender and political oppression with a singular passion and wit.’ Indeed, this offering of 70 devastating sonnets both disarms and charms the reader. Hayes’ generous employment of rhythm and imagery is to be expected, and the evidence of these accolades can be seen in his deliberate, and experimental use of form. He’s had an excellent decade, from winning the 2009 Guggenheim Fellowship to the 2014 MacArthur Foundation Fellow.

American poet Terrance Hayes’ latest poetry collection, American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin, is a series of sonnets that, as the back of the paperback declares, ‘traces the fault lines of race, gender and political oppression with a singular passion and wit.’ Indeed, this offering of 70 devastating sonnets both disarms and charms the reader. Hayes’ generous employment of rhythm and imagery is to be expected, and the evidence of these accolades can be seen in his deliberate, and experimental use of form. He’s had an excellent decade, from winning the 2009 Guggenheim Fellowship to the 2014 MacArthur Foundation Fellow.

In Sonnet 11 of the collection Hayes makes his intentions clear, writing:

I lock you in an American sonnet that is part prison,

Part panic closet, a little room in a house set aflame.

I lock you in a form that is part music-box, part meat

Grinder to separate the song of the bird from the bone.

Indeed, the sonnet form is integral here. Why? The New Yorker’s Dan Chiasson’s review of the collection offers this:

The sonnet offered an alternative unit of measurement, at once ancient, its basic features unchanged for centuries, and urgent, its fourteen lines passing at a brutal clip. These crisis conditions suit Hayes. He fashions a diary of survival during a period when black men are in constant danger.

American Sonnets thrives on repetition, employing it both as a stylistic gesture and as a baton, striking the reader with sentences loaded with political and personal weight, like the ever appearing line, ‘But there never was a black male hysteria’.

This sentence is indicative of the recent progression in contemporary African-American hip-hop and rap music which has seen many artists openly discussing ideas such as mental health, systematic injustice, and the more psychological effects of racism, hysteria and anxiety. Perhaps a consequence of the internet, or a consequence of America’s Trump administration, musicians such as Kendrick Lemar (who in April of last year won the Pulitzer prize) and Childish Gambino and poets such as Hayes or Javon Johnson mark a resurgence in creating work from the perspective of the black male in America with a poetic force that hasn’t been seen since Gil Scott Heron in the late 1970s.

These sonnets are weighted with anxiety. Like a high-pitched frequency, it’s in the background throughout. In light of American’s current political climate, how could it not be so? Hayes’ anxious tone combines with his vibrant imagery and oftentimes quite devastating turn of phrase, echo fellow contemporary American poet, Richard Siken, whose homoerotic, anxious and intense poetry carries a similar sentiment ‒ the struggle under an aggressively-white oppressively-masculine political system. Sonnet 34 in the collection demonstrates the similarity between the two: the physicality, the quiet rage, the anxiety…

I mean my mother here she the crazy bitch in me

She the way I weep she the way I break she manly

Trumpet I can’t speak for you but men like me

Who have never made love to a man will always be

Somewhere in the folds of our longing ashamed of it.

Many of the sonnets in this collection concern themselves with the writing process itself, including the opening sonnet which introspectively ponders the beginning of ‘the black poet’s century’. Hayes professes, ‘In a second I’ll tell you how little writing rescues’, and in Sonnet 75 continues to say:

My problem was I decided to make myself

A poem. It made me sweat in private selfishly.

It made me bleed, bleep & weep for health.

Even these contemplations of poetry and acts of writing itself aren’t free from the blend of political and personal agony which emanates from these sonnets. Terrance Hayes’ latest offering is electric, charged with political frustration and poetic illumination. A strong contender for the T.S Eliot prize, to win would be of all-the-more importance in the era of Trump.

Leave a Reply