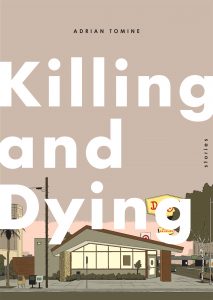

Killing and Dying

Killing and Dying, the latest comics anthology from Adrian Tomine is a collection of well-crafted shorts that reflect on modern life with dark wit but also poignant humanity.

Killing and Dying, the latest comics anthology from Adrian Tomine is a collection of well-crafted shorts that reflect on modern life with dark wit but also poignant humanity.

The collection comprises six stories, all of which work well both alone and in tandem with each other. Longer works are followed by shorter pieces. ‘Amber Sweet’ lightens the mood between two longer works featuring weighty social issues such as domestic violence. ‘Translated From the Japanese’ is a slower, more thoughtful story than its brash almost sensational predecessor, ‘Go Owls’, and picks up on themes of familial love that appear more substantively in the next story, ‘Killing and Dying’. Essentially, Killing and Dying has a natural flow to it.

The stories fit with one another not simply in terms of length, but also thematically and tonally. ‘Amber Sweet’ seems, on the surface, a lighter story complete with a happy ending, but lingering questions regarding the fate of the title character and her possible relation to the protagonist introduce an element of doubt. ‘Intruders’ likewise ends with its narrator hopeful but facing an uncertain future: ‘I walked up the block into the stream of oblivious, happy people…and starting right there, I tried my best to become one of them.’ Conversely, ‘Go Owls’, perhaps the darkest story in the collection, is peppered with comedy, and ends on the possibility of at least one character taking the chance to escape her unhappy situation. ‘Killing and Dying’, a deeply moving story filled with grief and bitter disappointment, is also a story about love, and filled with stand-up of both the cringe-worthy and laugh-out-loud variety.

This sense of dark undercurrents, nagging doubts but also unexpected moments of humour and pathos ties in with Tomine’s larger theme of exploring and satirising modern – especially American – life. An example of this satire would be the middle-class suburban mothers in ‘Go Owls’ meeting their dealer, whom they suspect of being a child predator, in a play park. ‘A Brief History of the Art Form Known as “Hortisculpture”‘ is a subtler example. Essentially, the story is of a gardener who discovers his life’s passion: creating sculptures fused with living plant life. When his idea fails to gain any traction, he destroys the sculptures himself. This particular story is formatted in the style of old black and white newspaper comics: it is arranged in groups of four panels, with three panels setting up a joke and the fourth telling a punchline. Occasionally, this is swapped for a full-spread comic in colour, much like a special issue taking up an entire newspaper page. These odd splashes of colour keep the format dynamic and engaging.

This sense of dark undercurrents, nagging doubts but also unexpected moments of humour and pathos ties in with Tomine’s larger theme of exploring and satirising modern – especially American – life. An example of this satire would be the middle-class suburban mothers in ‘Go Owls’ meeting their dealer, whom they suspect of being a child predator, in a play park. ‘A Brief History of the Art Form Known as “Hortisculpture”‘ is a subtler example. Essentially, the story is of a gardener who discovers his life’s passion: creating sculptures fused with living plant life. When his idea fails to gain any traction, he destroys the sculptures himself. This particular story is formatted in the style of old black and white newspaper comics: it is arranged in groups of four panels, with three panels setting up a joke and the fourth telling a punchline. Occasionally, this is swapped for a full-spread comic in colour, much like a special issue taking up an entire newspaper page. These odd splashes of colour keep the format dynamic and engaging.

With this style, Tomine harkens back to the history of comics, eliciting a feeling of nostalgia. However, while every fourth panel may be a punchline, unlike in the comics of old where the status quo was usually maintained, each new four-panel-group in Tomine’s line up shows the consequences of the last,  as we watch the protagonist’s family come under strain for the six years of his ‘calling’. The times Tomine is harkening back to, if they ever really existed, are gone. This is also another story with a seemingly happy ending that doesn’t quite sit right. Seeing the toll that pursuing his art has taken on his loved ones, the protagonist writes off his sculptures as ‘ugly’, and he and his daughter destroy them together. But was the protagonist deluded for six years, or is he deluding himself now? And why should someone have to choose between artistic fulfilment and happiness or stability for himself and his family? These are just some of the questions Tomine’s collection raises.

as we watch the protagonist’s family come under strain for the six years of his ‘calling’. The times Tomine is harkening back to, if they ever really existed, are gone. This is also another story with a seemingly happy ending that doesn’t quite sit right. Seeing the toll that pursuing his art has taken on his loved ones, the protagonist writes off his sculptures as ‘ugly’, and he and his daughter destroy them together. But was the protagonist deluded for six years, or is he deluding himself now? And why should someone have to choose between artistic fulfilment and happiness or stability for himself and his family? These are just some of the questions Tomine’s collection raises.

Overall, this collection a smart and sophisticated. Its playfully self-referential use of form lends additional dimensions to its stories. In tales filled with humour and heartbreak, Tomine exposes a dark undercurrent to everyday life, but also includes the odd glimmer of light breaking through.

Leave a Reply