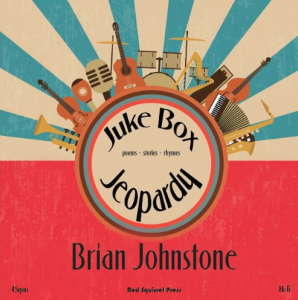

Juke Box Jeopardy

The first thing one notices upon picking up Brian Johnstone’s latest poetry collection, Juke Box Jeopardy, is the binding. The pamphlet comes in a brightly coloured sleeve, like a record. It’s a promise that you have picked up something unique, maybe even fun. And Johnstone delivers.

The first thing one notices upon picking up Brian Johnstone’s latest poetry collection, Juke Box Jeopardy, is the binding. The pamphlet comes in a brightly coloured sleeve, like a record. It’s a promise that you have picked up something unique, maybe even fun. And Johnstone delivers.

As the title and sleeve suggest, this is a collection about music. With infectious enthusiasm, Johnstone takes us on a journey through the history of his evolving relationship with music, from the boy who loved Tchaikovsky and had never heard of The Beatles, to the would-be musician experiencing a revelation at a The Incredible Swing Band concert. Throughout, he exhibits an almost obsessive knowledge of the music and artists he is discussing, dropping constant references to singles, albums and events in the artists’ lives, as in his tribute to Marianne Faithfull, ‘Faithfull’:

watching those tears you sang of go by,

as blue as the label that spun round

your name. How could this boy resist……this little bird singing on in my head

her appeal that I stay, keep the faith?

These references are carried with an air of playfulness, rather than arrogance, Johnstone makes it clear his goal is to share and celebrate these works, not to show-off. A series of ‘liner’s notes’ at the end of the collection, offering additional information, and a playlist at the start pairing each poem with a song, help keep less musically informed on-track. Johnstone isn’t above indulging in moments of self-deprecation either, laughing at the earnestness of his younger self in poems such as ‘Progressive’, in which a girl asks what genres of music he enjoys:

“Prog Rock,” I’d said,

so keen to get it right.She didn’t wait;

said, turning on her heel,“I thought you might.”

Thus, the experience of reading the collection is akin to that of a close friend eagerly sitting you down to introduce you to their new favourite band, until they are your new favourite band, too.

As might be expected, all of the poems possess a musical quality. External and internal rhymes abound, for example in ‘Elvis Gets His Gun’:

hung up at the store. They offered more

but he was sure, immovable for one

so young – a shotgun[.]

These musical qualities are not lost in the more experimental pieces, such as those following the Japanese haibun form – a blending of story and haiku. These poems feature prose infused with sound sense. Take, for example, the joufully alliterative line in ‘First Contact’: ‘This photo is clearly not the singing pigs Pinky & Perky, TV puppets whose Party Time EP his parents had bought him’.

The genius of certain other pieces lies in the way they work with the songs on Johnstone’s playlist. ‘The Ring She Left’ is a haibun recounting the time Sandy Denny left a stain on a piano at Johnstone’s old student union, and how it was subsequently removed. It is made an all the more poignant tribute to the deceased musician when paired with her melancholy song ‘Who Knows Where the Time Goes?’

The titular poem, ‘Juke Box Jeopardy’, a reference to Juke Box Jury, is about the struggle to be successful in the music industry (a struggle Johnstone himself faced). But the collection itself is a story of moving on from old tastes and old dreams, with the final poem ‘Desert Island Deserter’ narrating someone’s escape from the titular island of the music-themed radio show Desert Island Discs, using their eight favourite tracks to ‘paddle’ their raft. After all this nostalgia, Johnstone tells us, it is time to find something new. The final note of the collection is not bitter but hopeful.

Overall, Juke Box Jeopardy is an exuberant celebration of music for serious and casual fans alike. It invites the reader to not only reflect fondly on the past but also to look to the future with optimism.

Leave a Reply