You Can’t Read a Good Book Without Wishing You’d Written It: An Interview with Cynthia Rogerson

We meet in a restaurant situated at the water’s edge of the Cromarty Firth, just outside the Ross-shire town of Evanton where Cynthia Rogerson lives. It is early in the day because she will be on ‘grandkid duty’ later. She is the prize-winning author of five novels and a collection of short stories and it feels special to be engaging with her in the Highland setting which forms the backdrop to much of her work. As we settle down to coffee in a covered outdoor extension, the rain is lashing hard against the canvass canopy. I confess to her that I have come late to her work but have now serially read all her novels. She tells me she also has a confession – that she came late to writing and is also a binge-reader.

We meet in a restaurant situated at the water’s edge of the Cromarty Firth, just outside the Ross-shire town of Evanton where Cynthia Rogerson lives. It is early in the day because she will be on ‘grandkid duty’ later. She is the prize-winning author of five novels and a collection of short stories and it feels special to be engaging with her in the Highland setting which forms the backdrop to much of her work. As we settle down to coffee in a covered outdoor extension, the rain is lashing hard against the canvass canopy. I confess to her that I have come late to her work but have now serially read all her novels. She tells me she also has a confession – that she came late to writing and is also a binge-reader.

Rogerson read a lot as a child and kept a journal. She was also a prolific letter-writer, largely as a result of having moved to the UK at seventeen from her native California. Her creative writing experience started in her late thirties when, craving some activity beyond the home and her four young children, she joined a local writers’ group. The group met fortnightly and this gave her a structure and discipline for writing and a critical audience. She would often not write a piece until the day of the meeting but it forced her to prioritise her writing twice a month. All five members are now published writers and are still in touch socially.

Rogerson says she desperately wanted to be a published author because she loved reading; she says, ‘You can’t read a good book without wishing you’d written it – right?’ She began by submitting short stories to magazines and competitions. Her first breakthrough came when one of her short stories was shortlisted for the Macallan/Scotland on Sunday prize in 1998. Subsequently she was awarded a Scottish Arts Council Grant which enabled her to treat writing like a job and to pay someone to look after her children while she wrote her first novel, Upstairs in the Tent. She is on record as claiming not have a writing routine but was this a routine of sorts? Not really, she says – but she did use that time to write quickly and intensely. The first draft did not take long to complete although there were typically five or six revisions until she felt it was good enough for submission.

Rogerson says she desperately wanted to be a published author because she loved reading; she says, ‘You can’t read a good book without wishing you’d written it – right?’ She began by submitting short stories to magazines and competitions. Her first breakthrough came when one of her short stories was shortlisted for the Macallan/Scotland on Sunday prize in 1998. Subsequently she was awarded a Scottish Arts Council Grant which enabled her to treat writing like a job and to pay someone to look after her children while she wrote her first novel, Upstairs in the Tent. She is on record as claiming not have a writing routine but was this a routine of sorts? Not really, she says – but she did use that time to write quickly and intensely. The first draft did not take long to complete although there were typically five or six revisions until she felt it was good enough for submission.

Publication of her book was ‘a fluke,’ she insists. Whilst attending a book event with a friend at Waterstones in Inverness, her friend mentioned to author Andrew Greig that Rogerson had also written a novel. He offered his e-mail address and asked if he could see it. She duly sent him the manuscript by post and his feedback was positive. He suggested she send it to his agent in London. The manuscript was rejected and sent back within a week. When Greig asked his agent what she had not liked about the novel, she admitted she had been too busy to read it and asked to see it again. It was duly picked up by Headline, which Rogerson attributes mostly to Greig’s endorsement.

For her a book must be readable, convincing and have some emotional resonance. Rogerson cares about characters. It is important that they are credible – and flawed. The reader should think ‘Oh my God – I’ve had that thought too.’ They should find an echo. She grew up influenced by John Steinbeck, Henry James, F. Scott Fitzgerald because her father loved them and she respected his tastes. She still loves Steinbeck. Although Rogerson admires writers like Doris Lessing and Margaret Attwood, there are other authors to whom she regularly turns, notably Carson McCullers and Anne Tyler, and hopes their writing will seep into her own style. I remind her that she is often compared to Tyler,

That flatters me no end. I love it! I also love Tessa Hadley who writes about domestic things. Both she and Anne Tyler are treated as serious writers but they are unusual, I think, because they write about marriage and the home.

Rogerson’s creative ability to reflect the messiness and complexity of human relationships captivates me as a reader but I find the term ‘domestic fiction’ tricky. Is it just a lazy way of describing narratives in which relationships, particularly those played out in a domestic sphere, are closely examined? Rogerson feels all the best books are relationship-centred, even Tolstoy but it is women who are regarded as writers of domestic fiction; she cites Mark Haddon and Nick Hornby as current writers of domestic fiction but remarks that this is not recognised because they are men. I ask if this is because women are thought to be more interested in relationships than men? Rogerson thinks that might be true but also believes that writing about relationships has traditionally not been considered to be literary, Consequently there has been a knee-jerk reaction against it but she hopes this might be changing now.

The notion of ‘home’ is explored throughout her work. The home you occupy, the home you are searching for ‒ being homeless, feeling displaced, homes exploding, homes burning down are all variations on a theme. In Love Letters from my Death-bed, the character Morag describes herself as ‘a geographical bigamist’ and I wonder if this is owed, in part, to Rogerson’s experience of having lived in two countries. Recently she has been reflecting on this too and wants address it more consciously in her next book. She tells me that her Californian home – her parents’ house of 60 years – has recently been sold and, whilst she not lived there for decades, she is aware that she constantly feels restless. She is always wondering if there could be a better place to be:

The older we get, the more we seem to have this homesickness which I can’t define, I can’t pin down – a yearning for something we don’t even know. I think we yearn for where we have felt most comfortable – perhaps ourselves at three years old. I’ll never know what it’s like to live permanently in the place where I was born and I’m very interested in people who do that and how they view the rest of the world. Do they see incomers as slightly less valid in a way?

This idea of ‘the incomer’ is familiar to me, having also lived in a small rural Highland community. However, I question what is meant by ‘incomer.’ In my experience, the term is applied randomly, both to new residents and to those whose families have lived in an area for generations. We both laugh and agree that we are on slippery ground.

We laugh a lot. I explain that Love Letters from My Death-bed caused me to laugh out loud. It’s a romp and I wonder why she decided to set a humorous story around a hospice and whether it was as much fun to write as it was to read? Yes – it was fun, Rogerson admits. The idea came to her through facilitating creative writing sessions in a local hospice. This was an uplifting experience which was why she felt some disloyalty using a hospice setting for the novel. It was her prime reason for locating her fictional hospice in California, away from Highland Scotland,

We laugh a lot. I explain that Love Letters from My Death-bed caused me to laugh out loud. It’s a romp and I wonder why she decided to set a humorous story around a hospice and whether it was as much fun to write as it was to read? Yes – it was fun, Rogerson admits. The idea came to her through facilitating creative writing sessions in a local hospice. This was an uplifting experience which was why she felt some disloyalty using a hospice setting for the novel. It was her prime reason for locating her fictional hospice in California, away from Highland Scotland,

Death doesn’t seem scary any more when you are that close to it. I wanted to explore how our choices change when we face mortality. When we really do know we have a finite time our choices might be different – we might take lovers or spend money or take holidays – that’s what I wanted to talk about and it was wicked fun to write. I also took inspiration from Tom’s Midnight Garden – that’s a story about a little girl who is a ghost in Tom’s garden at midnight but actually she is not a ghost –she’s an old lady upstairs. It’s about time, immortality, the things which haunt us – I loved that book as a kid and love it still.

The novel was accepted for publication without anyone reading it, on the basis that she was already a published author. She now wishes there had been more scrutiny as she feels there are maybe too many plot-lines, and that possibly it’s too fragmented. She asks my opinion. I admit it took me a while get into the book due to the many characters, converging plot-lines and accompanying graphics but once I had grasped these, I loved it, particularly the fast pace and the dark humour. I single out one scene to which I returned several times – a group of female hospice volunteers are discussing a mutual friend who has recently been widowed.

‘Is that the chapter which finishes, “Lucky bitch?”’ Rogerson asks, giggling. She explains that during a recent gathering of female friends, someone read this chapter aloud, because we’re at that age where we might think of widowhood as sad but might also be quite envious of having the TV remote control to ourselves. I’m glad you remembered that – that brings me joy.

She writes about death and trauma with lightness of touch. Stories are told through the relationships of her characters as they face adversity. There is no dearth of adversity; psychotic post-natal depression, homelessness, death, traumatic childhoods, lost babies, a much loved teenage son killed in a road traffic accident. I am curious to know how intensely she researches these areas. She explains that she tries to make all her books credible but worries little about accuracy in the first draft. Once she has completed a draft, she will then look for expert guidance in terms of verification:

For instance, I would start with the abandoned baby and ask ‘how did this happen?’ In the California one I had to find out about the Californian Hospice movement because it is so different there to here. I also read a great book about palliative care which taught me that a lot of hospice patients slip away when no-one is in the room. I wouldn’t want my children to see me – would you? I would wait until they were gone – my little protective radar would still be on, unless I was completely demented.

We pause while Rogerson adjusts the patio heater and I gaze across the grey water to a rain-drenched Black Isle at the other side of the Firth. I tell her that I Love You Goodbye opened my eyes to the possibilities of taking risks when structuring a novel. It is a story told through four first person monologues. The town of Evanton appears intermittently as a detached commentator:

We pause while Rogerson adjusts the patio heater and I gaze across the grey water to a rain-drenched Black Isle at the other side of the Firth. I tell her that I Love You Goodbye opened my eyes to the possibilities of taking risks when structuring a novel. It is a story told through four first person monologues. The town of Evanton appears intermittently as a detached commentator:

It was very important to me to make Evanton real and I didn’t know how first person characters could convey this. Also there are things I wanted to say about small town life that I couldn’t let a first person narrator say. So it starts with what Evanton looks like from far and then zooms in – and I wanted that – for the reader to keep zooming in and out of the lives of the characters.

Elsewhere there are other clever structural devices; a commentary in the form of newspaper column in Upstairs in the Tent, a story told backwards in Wait for Me, Jack, characterisation of the A9 weaving its way through the story in If I Touched the Earth. All are exciting ways of binding the narrative together:

It happens in all the books – in the beginning it seems like a natural thing but then later I have to formally structure it in. None of the published books are anything like their first drafts – I only think when I write – it’s through the process of writing that the story emerges and I have to completely rewrite it from the beginning – so I’m not as clever as you think I am.

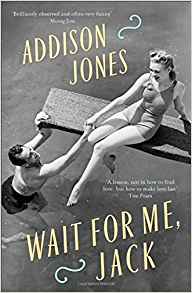

Throughout her life, Rogerson has been fascinated and bewildered by her parents’ relationship. Her latest novel, Wait For Me, Jack was a chance to examine it in semi-fictionalised form. She says she was intrigued by how two incompatible people, who often dislike each other, can stay together and share a life. It was difficult to write – not least because she chose to write it back to front. She didn’t want the reader to read the book to find out what happened but to find out where it began – to excavate, to scrape back the layers. It offers a series of backwards snapshots each taken at a certain time on a certain day. Because of the reversed passage of time, when she introduced something new in, say, Chapter 6 – she would have to go back to Chapters 3 and 4 to interweave it. This resulted in the book being rewritten twenty times.

Throughout her life, Rogerson has been fascinated and bewildered by her parents’ relationship. Her latest novel, Wait For Me, Jack was a chance to examine it in semi-fictionalised form. She says she was intrigued by how two incompatible people, who often dislike each other, can stay together and share a life. It was difficult to write – not least because she chose to write it back to front. She didn’t want the reader to read the book to find out what happened but to find out where it began – to excavate, to scrape back the layers. It offers a series of backwards snapshots each taken at a certain time on a certain day. Because of the reversed passage of time, when she introduced something new in, say, Chapter 6 – she would have to go back to Chapters 3 and 4 to interweave it. This resulted in the book being rewritten twenty times.

For me, the book has a different feel. It’s the only one written under a different name. Addison Jones is a fusion of Rogerson’s middle name and her maiden name. James Addison was her grandfather. The change was suggested by a new publisher who felt it might attract a new audience, thereby boosting sales. I like the front cover – a 1950’s photograph, originally published in Life magazine, of a swimsuit-clad woman sitting on a diving board extending her hand to a man in the water below her. Rogerson is also very happy with the image, so happy that she wrote an additional chapter around it. She has not always been pleased with the covers chosen for her books, particularly the image of a Japanese young woman in a white gown which appears on the cover of If I Touched the Earth. I agree that it doesn’t seem to reflect anything in the book and would not attract me to buy it. She explains that publishers tend to offer authors a limited choice of options but ultimately will choose the image they like best, and is often influenced by marketing staff. She’s not sure why the writer’s judgement is not trusted more as they are attuned to their own sensibilities and those of their readership.

She is currently completing a collection of short stories. There are plans for a novel, the plot ranging over a 24 hour period. She already has a title – Day of Departure. It will be the story of two people shedding one reality for another and will include a death. But there is a back-log so this must wait. She is also hoping to develop some memoir pieces she wrote whilst sitting by her dying mother’s bedside last year.

They are memories from my teens – exactly as I remembered them, written in the first person. Usually if I write in the first person it’s never about me. It was very liberating. There are six stories which I could build up – although I’m not sure about publishing them – I wouldn’t want my kids to know this stuff. No-one ever wants to know about their mother’s sex life. Perhaps I could rewrite them in the third person or perhaps they might go ‘Oh that was when Mum was an adolescent – those were the free love days or whatever.’

Towards the end of our conversation we talk a little about Rogerson’s activities as a Royal Literary Fund Fellow; her work in schools and her support for university based creative writing programmes, all of which she enjoys. She currently also facilitates a weekly literary appreciation class at Eden Court Theatre which she describes as ‘fun, not academic – just fun!’

Given her support for emerging writers, I ask her what her tips for a fledgling author might be. She needs impressively little time to formulate her answer:

- don’t pay any attention to rules,

- write about what interests you rather than what you think is marketable or trendy

- and just write the damned thing.

- expect to think it is horrible – every writer does – most writers will give up at this stage but people who need to write will keep writing and it will come right.

I thank her earnestly for this and for her time and her generosity. The morning has been – well, immense fun. Outside the pewter sky is changing to silver. As Rogerson heads to Evanton and, no doubt, to grandchildren, I linger a while longer. Everything comes right in the end. Right as rain.

Leave a Reply