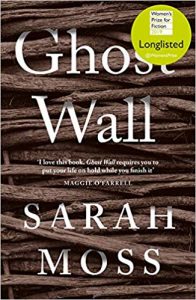

Ghost Wall (longlisted, 2019 Women’s Prize for Fiction

The moors of Northumberland remain wild. Despite the encroachment of pylons and roads, the bogs still hold secrets of the past and dangers in the present. Sarah Moss evokes the stark beauty of the moors in her sixth novel, Ghost Wall. In fewer than 150 pages, she weaves a tale of prejudices, cruelty, rage, mob behaviour, and, possibly, hope.

The moors of Northumberland remain wild. Despite the encroachment of pylons and roads, the bogs still hold secrets of the past and dangers in the present. Sarah Moss evokes the stark beauty of the moors in her sixth novel, Ghost Wall. In fewer than 150 pages, she weaves a tale of prejudices, cruelty, rage, mob behaviour, and, possibly, hope.

Seventeen-year-old Silvie’s Northumbrian father uses his holiday time and money to take his family on an Experiential Archaeological programme with Professor Slade and three of his students. They re-enact the living arrangements of an Iron Age community in dressing, eating, hunting and gathering, and sleeping. Silvie meets southerners for the first time, with their access to travel, and self-assurance that they can speak to others as equals. What happens is surprising, though foreshadowed in the opening pages:‘They bring her out. Not blindfolded but eyes opened to the last sky, the last light.’ In those sixteen words, Moss drops us into Iron Age Britain as a sacrifice is led to a bog. On the next page, when she introduces Silvie, Moss sketches an abusive father in similarly few words: ‘My mother sat on the stone where my father had told her to sit.’ She uses two voices in Ghost Wall. One belongs to an onlooker of the Iron Age sacrifice; the language is formal and lacking contractions. The other belongs to Silvie, whose language is modern, even though many of her thoughts seem to belong in the nineteenth century. Moss’s writing is clear, bright and avoids telling, relying on crafted phrases to evoke her messages.

On the surface, Ghost Wall is about the promise of Sylvie’s release from a life indentured to her father. Silvie’s world-view raises the spectre of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. She is an intelligent person, who is proficient at wildcrafting skills, and knowledgeable about history, all learnt from her father. But there are strong signs of Stockholm Syndrome about Silvie, not just around her father, but in her quickness to defend any male. A lifetime of subservience has taught her this kneejerk reaction to any whiff of criticism of men. She believes they matter more than women.

Just submerged in the flowing waters of the novel, Moss highlights the state of intra-national relations in Britain. Silvie is suspicious and prickly in her first interactions with the students, only a couple of years older than she. She expects them to be toffee-nosed southerners, and, at first, they do appear to be prejudiced, being surprised Silvie’s bus driver father knows about Iron Age Britain. However, they prove more open minded than she and respect Silvie’s and her father’s wilderness skills. Her inverted snobbery, however, rises again and again throughout the book. Usually, her instinct to kindness wins through.

Look closer still at the darkest waters, and you’ll see flickering there an examination of genetic memory. Consider – do we, with relatively little prompting, revert to older ways of maintaining: of surviving and entertaining ourselves? There is warning in these lines: ‘Mum and I gave each other one look as Dad and the Prof stepped in and did a strange male back-slapping move, like gorillas. I had never seen Dad touch another man before, didn’t know he knew the steps.’ Relationships gel around mutual needs and crowd behaviour blossoms easily.

In the chilling climax, Sylvie, product of a lifetime of bullying, is swept into a dangerous situation. It is the archaeological student, Molly—the girl Silvie would like to be—who averts tragedy. In the last pages we can imagine a brighter future for Silvie, but when she refuses a doctor’s treatment and photographs of her condition, we are left wondering, will she allow things to change for her?

Sounds like a remarkable tale! Nice review Rhoda.