The Circus March by Gertruda Straigyte

I say to my daughters

never trust March

for its joy comes in a quarter

but takes full month’s charge

January 13, 1991

The Soviet Union president demands the restoration of the USSR constitution in Lithuania. When the Lithuanian government disagrees, tanks and trucks with armed soldiers fill city streets. The Lithuanian prime minister calls upon independence supporters, ‘Beloved people, though we lack television and radio which is painful in our predicament, it is far from over. Lithuania lived without television, survived, fought, won independence and will win independence again. Marionettes in Lithuania will fool no-one, we need not follow their law, nor participate in their government’.

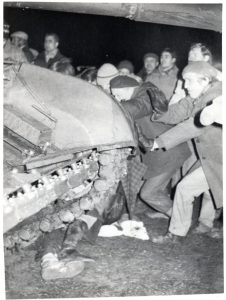

Responding to his message, people from all over Lithuania come to defend their government. At 2 am, combat vehicles arrive at the Vilnius television tower. They find anti-tank barricades built by people who sing, pray and shout pro-independence slogans. Soldiers are ordered to ignore them.

‘I begged him not to go’, says my mother, 25 years later. ‘I was pregnant with you, scared as hell. Streets were empty – everyone home trying to get a radio signal, but nothing apart from pffffff pfffff’ – she screws up her face and laughs. ‘But he still went. You know your father.’

14 people were killed that night –some by tanks, others shot. That March Lithuania became the first Soviet republic to declare independence. 10 years later, I was asked to speak at school in memory of the January events. I stood in front of everyone, pale and humped. With my teacher’s nodded approval, trembling like an aspen, I spoke:

I can no longer bear my thoughts of you,

Like an apple tree, heavy with fruit,

my arms are laden with loss.

But you say to me:

‘Stand tall, as freedom stands’, my father commanded when marking my height on the kitchen door. I knew he was joking, but I was too scared to laugh. When he was done, he looked at any new inches with such pride that I prayed to outgrow my three tall sisters, all born in summer.

I was a wan child of March. ‘They kept you in hospital for two weeks when you were born. You were too pale beside other newborns,’ mother says. I notice the veins on her arms; they suit her more than any jewellery. They look like waves on the sea shore. I have never met anyone so passionately in love with the sea. She used to run into it the way people run to each other after years of exile. Mother catches my eye, ‘until they saw your father, of course.’ I ask why it took him two weeks to visit us and she assures me that times were different. I don’t believe her.

On Tuesdays we eat fish

Early afternoon in March

Around 1 o’clock

Just you and a carp in the kitchen

Staring at each other

Girls are playing clapping games

miss ma–ry mack mack all dressed in black black

It’s a day like every other day

You try to tame a swallow

It flies away

3 o’clock

Her cheeks blush from the pain

It’s time

Cries she while crawling downstairs

Looking down at you

the saddest human child

5 o’clock

She is taken away

Sun is taken away

Both hide behind the motels

To give birth to another day

***

On Wednesday father left to get some cigarettes and did not come back for two weeks

‘Dad, you are bleeding!’ I yelled when I saw him sitting on the stump with an axe in his leg. He sat there like one of his sculptures – calm, and remote, looking at me as a spider looks at a frightened fly stuck in his web. He just sat there and bled. As red coloured sawdust flowed towards me, I jumped back and ran to get my mother, screaming my dad is a beast!

She hit me with the belt for these words.

how dare you

how dare you

He was a tall red headed boy born in the village called Išlaužas, who moved to Kaunas at eighteen (to create art and kiss women), but never forgot his hometown. His family is buried there, his parents and siblings. Their gravestones were all sculpted in our garden, with not a single tear, just the sound of the hammer.

She was the most beautiful woman. Recently separated from her first love she was introduced to my father. ‘I liked that he didn’t talk much, and how smart he was. I needed someone like him in my life.’

A tension

Attention, attention

I found him

In Petrawski’s street

Second floor

He carves his angels in silence

His hands are reckless and cold

Attention attention

I knew then

My story would be retold

I’ll give him my youth

And four daughters

I’ll forget the idea of gold.

‘Two sugars for me, Claudel’ I hear my auntie and mother at the kitchen. She pours coffee into tall ceramic mugs; little puffs of steam play on her lips while she counts teaspoons of sugar. I feel deeply moved and sorry for my mother, for all that she had to go through and how unfair life has been to this woman. People announced him as a talent, a maestro, while she was simply his young wife who raised kids and cooked dinners. For years we were allowed to eat only when he came to the table. He was stubborn, strict and apathetic. He made us poor,refusing to sell his works, but still her love for him was extensive, and blind.

‘He kissed me on the forehead and I knew’ says my mother when asked if Dad ever told her he loves her. ‘But has he never said…’ ‘No’ she interrupts and looks at her apron. ‘But I knew it, I just knew.’

First date

tell me my beloved have you ever planned

to come back home with me

when trees swallowed the sun

as a purple candy

when there was no fear

no modesty

just rain drops falling on your hair

promising autumn but bringing nothing

when I showed you my scars

repulsive

but mine

you wiped down my blood

thinking it cherry wine

when the flag was raised

on Sunday

as usual

loud steps

orchestras

the beginning of every war is so beautiful

when the neighbours intensely whispered

don’t

don’t go

don’t go home with him sister

***

silence

after the fight

I am lying on my back

I cannot tell

have I won

have I lost

perhaps both

‘No! Not enough! These are my babies,’ yelled dad whenever someone offered him money for a sculpture. It got worse when they haggled – he threw them out of the house. I say it now though I knew it then – his attachment to wood offended me and made me turn my back on art. I remember he shook up the house when I refused to go to art school. ‘No matter what you do, no matter what you want, you have to know.’

game of colours

substance of clay

weight of stones

power of the pencil

form of a bust!

Don’t let me fail

Enough

put down the book

stop clapping syllables

just for one day

take me outside

and show me bees and dragonflies

teach me how to smile and laugh

when ridiculed behind my back

tell me that there is no god

and save me time

then guide me through betrayal

I’m weak

I’ll die

show me how to raise

my voice

my hand

my child

reveal a thousand ways

to make a passion last

just for one day

tell me how to cheat

to fake a cough

to wash a blood stain from the sheet

and how to be a person

defined as ‘okay’

for I have learned a lesson

the only one though

for most of the time being

‘okay’ is absolute enough

First – loud steps, then –a few bangs, after that – a sound of breaking glass and finally, a hysterical cry. Crying spreads easily and it takes only a few moments for the house to sink in tears. ‘We don’t have anything’ whispers my mother, picking up pieces of glass from the floor until she notices me. She drops everything and hugs me so tight that when she finally lets me go my breath hurts my chest. She takes my face in her hands and I see guilt running down her cheeks. Later that night, as every night, she comes to my bed to pray, but instead of saying amen and switching off the lights, she whispers, it’s always March here and always Monday; Jose Arcadio Buendia is not as crazy as the family said, and falls asleep in my bed.

From that night my father slept in the kitchen. Every time mother came into the kitchen, father turned up the volume on the TV. Television consumed my dad. I grew up wishing that 13 01 1993 could have ended differently.

To Mikhail Gorbachev

take away our TV

and we will be free

for no man can be free

when a slave of TV

‘Now go and tell your father’, she says and gives me back my notebook. I got a low mark in math because I am the only child in the class whose parents can’t afford a tutor.

I plead, ‘please no’

‘can you tell him’

‘he doesn’t want to know, if he wanted to he would ask’

‘please, mom, I’ll do better next time’

‘no, no please not that’.

I go on and on until she closes the balcony door disappearing in a cloud of mint smoke. Right here, right now, I wish to disappear.

I sit next to him, say hello and swallow saliva as a child who has been told to apologize. We don’t know each other. We don’t look at each other.

Small talk

I want to say ‘hold me’

But I am too shy

I want to say ‘I miss you’

But it’s not quite true

So I say ‘bless you’

I want to say ‘good bye’

But I might be back

I want to say nothing

But it will be too quiet

I want to say ‘it hurts’

But I have already said that

So I simply suffer

I want to say ‘I am confused’

But so is everyone

I want to say ‘will you’

But I know that you won’t

So I say ‘oh well’

I want to say ‘brilliant weather’

But it’s not brilliant

So I say ‘it’s 7 am’

I want to say ‘no worries’

But it would be a lie

So I stay silent

Because why say anything

Ever

At all.

***

March, 1997. I sit on a wooden roundabout horse. My father left me here to go for a cigarette. He doesn’t come back after the first run, or after the fifth run. I start feeling dizzy and want to get off, but he told me to stay here. I am too scared not to. I let out a painful cry, but the looped circus music washes away my voice. I fall down and hurt myself. They stop the carousel and surround me. ‘Where is your dad-e?’ they ask. Where is your dad-e?’ they slowly repeat.

‘I am here’ comes a bitter voice from the crowd.

I see him make his way to me, holding candy floss above everyone’s heads like a pink balloon. He reaches me and holds me in his big arms. Right now, in this moment, I love this man more than anyone else.

Notes

[1]‘Stand tall, as freedom stands’: Justinas Marcinkevicius’ poem ‘Freedom’

[2] Išlaužas: Name of this village means from the bonfire

[3] Claudel: Camille Claudel, the lover and co-worker of sculptor Auguste Rodin.;Claudel lived in the shadow of Rodin and later appeared to be mentally ill.

[4] ‘it’s always March here and always Monday; Jose Arcadio Buendia is not as crazy as the family said’:A line from One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, which is my mothers’ favourite book that she knows by heart.

You can smell Lithuania from this text… Love you! :))