Space, Place, Time: A collage essay by Cheryl McGregor

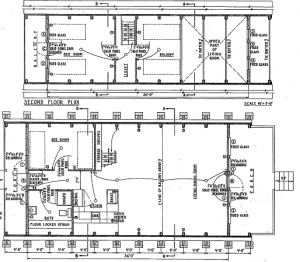

Building A House

I have always been taken with the word ‘stanza.’ It has to do with its architectural etymology. It comes from the Italian word for ‘room’ and upon learning this, I thought: of course. Aren’t all great works of poetry just like houses? Or hotels? Buildings? Be it drawn from the words of e.e. cummings, Mary Oliver, James Fenton, or Seamus Heaney. A hotel, a haunted one, constructed by T.S Eliot; or a sleazy motel built from the words of Bukowski. Each room of each poem containing its own secrets, observations, confessions. Its portraits and sketches. Its sounds, its melodies.

I have always been taken with the word ‘stanza.’ It has to do with its architectural etymology. It comes from the Italian word for ‘room’ and upon learning this, I thought: of course. Aren’t all great works of poetry just like houses? Or hotels? Buildings? Be it drawn from the words of e.e. cummings, Mary Oliver, James Fenton, or Seamus Heaney. A hotel, a haunted one, constructed by T.S Eliot; or a sleazy motel built from the words of Bukowski. Each room of each poem containing its own secrets, observations, confessions. Its portraits and sketches. Its sounds, its melodies.

And the spaces between the stanza assume the role of a corridor.

Allowing you, the reader, to travel through; considering the room you have just left, considering the room you are about to enter.

The contemplative corridor. The pause.

It’s all perfectly constructed. Designed in accordance perhaps with the same set of principles as great works of architecture?

The Principles of Design :

Balance / a distribution of equal visual weight

Alignment / an arrangement forming a straight line

Emphasis / an accentuation of importance

Proportion / a scaling of objects in relation to each other

Movement / a directed path of optical motion

Pattern / an orderly repetition of an object

Contrast / a juxtaposition that accentuates difference

Unity / a harmonious arrangement of elements

But isn’t writing like this?

Construction value. Putting together the pieces. Suturing. This is the very form of poetry: the poetics of form.

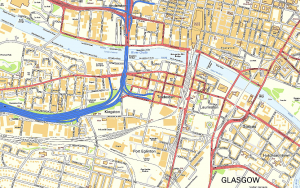

I am a different person depending on where you find me

In Copenhagen I was a hippy, strolling around Christiania’s lake with a beer in hand. I had grazes on my ankles from cycling over the river, through the Meat Packing district, the Ungdomshuset, the boroughs. We ate from carts and Seven-Elevens and got deliciously lost every day. I slept in a room with fifty-nine other people. The noise of fifty-nine people snoring sounds like the ocean.

In Brussels, I was a young professional. We ate langoustines outside the Fin de Siecle and perused the boutiques. I took taxis everywhere and made the city uncomfortable with my bad French. Kept a diary and drank gin with ice tea. I slept in a house decorated with art and plants that weren’t dead.

In Sweden, I was out of place and out of shape. I couldn’t make sense of the gold coins in my purse so I didn’t use them. Everyone I spoke to spoke in perfect English, but we still didn’t understand each other. When I came home, I was out of mind. I didn’t really sleep.

In Glasgow, I am awake. And I can be anyone I want. I meet people in bars and tell them fake names, and laugh because I might see them again and forget who it was I pretended to be. I sneak out of apartments in the dead of the night and make my own way home, alone.

In Glasgow, I am awake. And I can be anyone I want. I meet people in bars and tell them fake names, and laugh because I might see them again and forget who it was I pretended to be. I sneak out of apartments in the dead of the night and make my own way home, alone.

Back at home, I am stiff and heavy. The floorboards groan as I enter. The building has changed, and it tricks me. The cups are in the wrong place. The walls are much thinner, they give away secrets. I sleep on the couch, my bed is gone.

I feel sad when I’m at the beach, but in the healing sort of way. I don’t sleep when I’m there for fear that the sea may carry me out with it.

In the forest, I am a wild thing. I don’t worry about hurting myself. I climb trees. Take a nap in the hollowed-out caves of the pine-laden floor. It doesn’t hurt.

In the library, I work. I walk along the rows of books and wait for them to reveal themselves.

In Paris, the music didn’t stop. I felt light, I wore red shoes and the sounds of saxophones followed me most of the way. The traffic scared me. I don’t remember where I slept, I was too young then.

In Paris, the music didn’t stop. I felt light, I wore red shoes and the sounds of saxophones followed me most of the way. The traffic scared me. I don’t remember where I slept, I was too young then.

On public transport I feel sick. I feel sick when I’m travelling, but staying in one place makes me sicker. Like everyone else, I travel to find myself. I pick up (and drop) little pieces of me along the way.

Practical Magic

I have seen what good a garden can do. I have seen it with my own eyes.

It is no secret – Kipling knew it, Wordsworth knew it, as did Chaucer, Dickinson, Marvell, Blake, and Browning. I first read of its magic through Frances Hodgson Burnett. Not that I needed to.

I have seen it firsthand with my own eyes: the neighbour’s pear tree hanging so generously over the brick wall, dropping fruit with grace. Summer butterflies. Practising handstands. Watching clouds.

There’s another sort of magic to gardens. Less imaginative, more practical. There’s one near my apartment where addicts tend to themselves through tending to the leaves of their cabbages. They don’t need their poison, they found salvation in fertiliser. And old women, with their children all grown and gone, busy themselves with the season’s offerings. Berries, potatoes, carrots – eating alone becomes less lonely.

It gives energy to the tired, calm to the frantic, purpose to the purposeless.

Armed with a shovel, I too found this type of practical magic. I found it at the bottom of my own back garden.In ‘Digging’, Seamus Heaney wrote that pens can be spades. That’s all well and good but sometimes the only cure for the crazy is to put the blasted pen down, pick the shovel up and just dig. And that’s what I did. I dug as the sun crawled across the sky. Dug even though I felt like stopping,

Armed with a shovel, I too found this type of practical magic. I found it at the bottom of my own back garden.In ‘Digging’, Seamus Heaney wrote that pens can be spades. That’s all well and good but sometimes the only cure for the crazy is to put the blasted pen down, pick the shovel up and just dig. And that’s what I did. I dug as the sun crawled across the sky. Dug even though I felt like stopping,

Destroy the body just a little and watch the mind heal itself. Spines bending over earth; blisters burning on palms; gravel in the mouth; dirt in the eyes and finally… quiet.

H.G. Wells said ’We are kept keen on the grindstone of pain and necessity.’ I keep myself keen on the green of the garden, only a few streets away. It takes care of me, and I try to take care of it.

Benches and Baudelaire

Where I grew up, there were no benches. We walked around with permanently wet arses. We sat on the steps of the pavilion, or the church, or upon tree stumps. If worst came to worst, we flung our jackets down and sat on them.

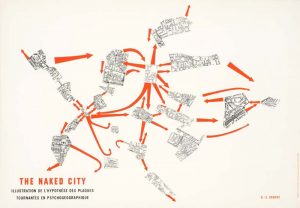

I had never considered, until I learned more about architecture, how cruel it was that the town planners didn’t give us anywhere to sit. We weren’t considered. The general consensus was that you sat on your couch or in your classroom seat or at your office. If you were out on the streets, you should get to where you’re going and not drag your feet. But human beings don’t work like that.

Where is the space for the flânerie? How does one catch their breath amidst the hostility of public architecture?

‘Hostile architecture,’ sometimes referred to as ‘unfriendly architecture’ is all around our environments. The Macmillan dictionary defines it as: the design of buildings or public spaces in a way which discourages people from touching, climbing or sitting on them, with the intention of avoiding damage or use for a different purpose. Examples include narrow, slanted bus shelter seats that are barely suitable for sitting on (and impossible for a homeless person to sleep on), benches with bulky armrests or protrusions which prevent people from reclining or sitting for long periods; jagged, irregular paved areas in order to deter skateboarders, bollards under bridges and flyovers to prevent skateboarding.

‘Hostile architecture,’ sometimes referred to as ‘unfriendly architecture’ is all around our environments. The Macmillan dictionary defines it as: the design of buildings or public spaces in a way which discourages people from touching, climbing or sitting on them, with the intention of avoiding damage or use for a different purpose. Examples include narrow, slanted bus shelter seats that are barely suitable for sitting on (and impossible for a homeless person to sleep on), benches with bulky armrests or protrusions which prevent people from reclining or sitting for long periods; jagged, irregular paved areas in order to deter skateboarders, bollards under bridges and flyovers to prevent skateboarding.

Sometimes it is obvious. Sometimes I even understand it. Anti-seagull spikes, anti-graffiti paint. If you don’t want your city to be covered in bird shit and paint tags then I guess it makes sense. But when did public space become exclusive?

A bench allows passive participation. When sitting, one becomes part of the painting. You can be present, and gloriously absent too. Osmosis. I admire Dundee because of its multitude of benches. It is a city that lets you sit. A sit-y, if you will.

The sheer pleasure of sitting outside the Caird Hall, listening to the buskers , watching older women defiantly carrying their shopping or the businessmen on their phones. One autumnal afternoon, my favourite of the Dundee buskers collective played a particularly soul-affirming rendition of Dave Van Ronk’s ‘Green Rocky Road.’ I felt calm. I felt a part of something.

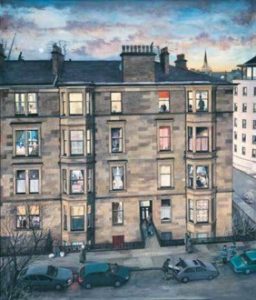

Make the Concrete Sing

In the spirit of a manifesto, I propose that architectural writing be used as a reactionary tool against nature writing. The urban environment warrants romanticising as much as the forests and fields, the beaches and the cliffs, the caves, the coves, the countryside.

There may not be flowers – save the little dots of purple that spring up out of mossed lanes – but there is paint and the kids know how to use it. Colour exists everywhere in this grey kingdom. Observe how the traffic lights glow on the wet tarmac, little puddles of green, yellow and red.

Let the city streets be your gallery space, observe the glass paintings, see the life that they contain.

Let the city streets be your gallery space, observe the glass paintings, see the life that they contain.

Natural symbolism cannot be refuted, it has its time and its place. But for those of us who don’t exist in those spaces, we must make the concrete sing.

You tell them you want to write poems.They give you prompts about the seaside, which you scarcely remember from childhood summer holidays. They show you poems written about mountains. You’ve never seen one. But you can close your eyes and see skylines, these have been imprinted on you. Scaffolding. Bricks and mortar. Railings. Grit and grey rubble.

Ignore the slander that ‘architecture disappeared in the twentieth century.’

Epilogue

I have a strong aversion to the notion of being misunderstood, or having not explained myself clearly. There also exists that strange pain, which I’m certain must be familiar to all who undertake creative work. When is a piece of work ‘finished’ and ready to be passed on?

Perhaps Beth McDonough is closer when she says,

These lines are not biddable. These lines want to loop countries, swim past continents, weave through language and memories. These are not words I intended to write, to fulfil what I thought or planned, what I filed or knew. These aren’t the lines that knit my uncertainties. This is the poem I don’t know. The poem I have yet to find out.

Who wields the power? Poet or poem? Essayist or subject? The entries seemed to have merely formed themselves, irrespective of my intervention, into their own being.

‘If an essay has a “motive,” it is linked more to happenstance and opportunity than to the driven will.’ Essay-writing relies on that element of construction; of building something out of these fragments of thought, feeling and memory.

In the future, perhaps ‘Constructing a Poem’, ‘Benches and Baudelaire’ and ‘Make the Concrete Sing’ could find a way to suture themselves together. Perhaps I have little control over what shape comes from them.

Retrospectively, I can see now what draws me in, what abstracts I have plunged myself into. Space. Place. Time.

Maybe we are all just mediums, vessels for the words to organize and express themselves through us, and not the other way around. Now I am left with five fragments and an epilogue.

Five potential beginnings, middles or endings.

Now I wield a Darwinian pen: I hope to trace their evolution.

Leave a Reply