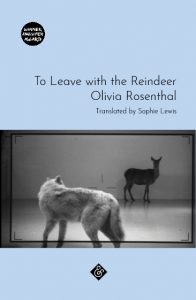

To Leave with the Reindeer

‘You don’t know if you like animals but you’re desperate to have one, you want a creature.’

‘You don’t know if you like animals but you’re desperate to have one, you want a creature.’

So starts this captivating and strange novel by Rosenthal in this new translation by award-winning translator Sophie Lewis of the 2010 original. Is To Leave with the Reindeer a novel, though? The book’s writing is a hybrid of two distinct discourses, intertwined yet not fully joining until the final pages. The two discursive strands are built into the one book in alternating paragraphs, each separated by white spaces.One discourse is a possibly autofictive, a story of growth from childhood to adult, a Bildungsroman almost, but in a way that is in itself disorientating – the ‘you’ is not my ‘I’ but another’s. The second discourse is formed of paragraphs from a variety of sources, all relating to animals and their place in the human culture – vets, abattoir staff, legal documents on breeding, a wolf-introduction project (the original inspiration for the book); these third-party paragraphs appear to be written in the voices of their original sources. As the book progresses, paragraphs from the life story increasingly mirror the stories contained within the third-party paragraphs.

Throughout the book the author references movies and uses them as metaphor. The conflating of animal and human story is most obvious in the allusion to the movie Cat People ‒ in its title but also in its subject (a woman who, if she consummates her marriage, will transform into a panther). In the book the narrator identifies with this impending ‘metamorphosis’, although also acknowledges: ‘You don’t wish to be like her. And yet, when she’s weeping in the bath because her first metamorphosis has actually happened, you weep too.’ However, as the end of the book approaches, the growth of the writer, and her joy in her change, is beautifully shown by the line ‘Unlike the cat woman, your metamorphosis does not herald the end of you. Emancipation takes forms you never imagined.’

The human life story starts with early childhood, and follows the narrator’s growth from complete dependence through life stages: identification ‒ ‘you are imprinted’; desire for separation ‒ ‘you want to betray them’; budding transformation ‒ ‘Your metamorphosis is imminent’; and integration of the self ‒ ‘Age has set you free.’ The use of the second-person voice allows a mature note for writing and reflecting on the past:

From the age of three, you begged for an animal, a little ball of fur that would be entirely under your sway, in your possession, your control, in your hand, in your power: yours.

the narrator’s sexual confusion in the face of these external forces is a developing theme. After going to see King Kong with her mother she says:

We may infer many things about ourselves and our sexual identity from the character in King Kong – the blonde, the lover or the gorilla who ravishes women – with whom, without actually admitting it to ourselves, we identify.

The narrator admits she identifies with the gorilla, but says nothing to her mother because ‘to lie you’d have to speak.’ This last quote comes at the end of a paragraph; she uses this technique throughout ‒ short declarative lines are often repeated at the end of several paragraphs in different forms, giving a cohesion and a sense of forward movement to the text.

We are cruel to animals even though we say we love them, To Leave with the Reindeer tells us, but we are just as cruel to people, especially ourselves. The writer seems to think we can gain a degree of mastery over both, but in protecting one we may have to hurt the other.

Leave a Reply