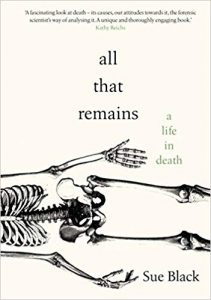

All that remains

If the intriguing title of this book invites you to expect something different, then read on and you won’t be disappointed. Dame Professor Sue Black, as one of the country’s leading anatomists and forensic anthropologists, is no stranger to death; her thoughts on death and its inevitability, which has featured in both her personal and professional lives, is expressed here with remarkable candour and honesty, and also with disarming tenderness.

If the intriguing title of this book invites you to expect something different, then read on and you won’t be disappointed. Dame Professor Sue Black, as one of the country’s leading anatomists and forensic anthropologists, is no stranger to death; her thoughts on death and its inevitability, which has featured in both her personal and professional lives, is expressed here with remarkable candour and honesty, and also with disarming tenderness.

Sue describes many disparate events in her working life in detail including, for example, her time in Kosovo with the British Forensic Team who were tasked to unmask war crimes. Their work on human identification from body parts was unbearably difficult and distressing ‒ bodies ‘accessible to insects, rodents and packs of wild dogs’ and ‘boiling with maggots’ ‒ but these unpalatable facts are related to the reader with clarity, and never with sensationalism. Such is the power of her words that it is almost impossible not to imagine yourself there, and admiration for the work of Dame Sue and the rest of her team just grows and grows the more you read. There are many other potentially upsetting stories around her work where her expertise has assisted and been key to important crime-cases across the United Kingdom but, again, her matter-of-fact writing style makes the telling of the stories compelling.

However what makes this book such a fascinating read is the way she also includes stories of her own family, and their deaths and reactions to death. If the death of much-loved grannies, and other relatives, is told with the same candour, we can sense the huge loss and the strong love experienced, making sense of mourning in a warm and very human way.

Throughout her working life at the University of Dundee, Dame Sue was ‘privileged’ to work with donated bodies, our silent teachers as students called them, and her level of respect for the human body and for the importance of the study of anatomy is palpable. Whilst she underplays her influence, the important work that she and others did in turning the University’s anatomy department into the Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification is impressive and uplifting. In the book she describes the Centre’s turn to forensic anthropology which resulted in Dundee becoming a go-to sight for police forces the length and breadth of the country. The well-described move to Thiel embalming placed CAHID in a unique position in the UK and the benefits it brought have been as she predicted and more. The book offers clear insights in a way that is gripping rather than off-putting. Her disclosure about infant osteology and the Scheuer collection put together by her dear friend Louise is done in such a sensitive way too.

Dame Sue’s reputation as an excellent anatomist and forensic anthropologist continues to grow through her many television appearances, including that of BBC2’s Cold Case series. This leads the reader to possibly expect an academic and scientific approach to the writing of this book. The content of the pages may sate such expectations but it is the way that Dame Sue perceives death and its consequences as personal alongside its benefits to the living that makes this book an entirely worthwhile read.

I now feel I know Dame Sue and her husband, Tom, and her daughters, very well, and All that remains will have this effect on all its readers. Her generosity of spirit runs through the book, ‘a life after death’ indeed. Read it, enjoy it, and make it top of your bucket list reading!

Leave a Reply