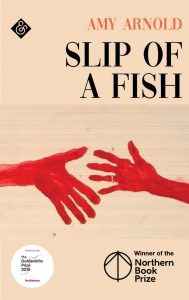

Slip of a Fish (Shortlisted, The Goldsmiths Prize 2019)

Amy Arnold’s novel Slip of a Fish is an exuberant exploration into whether language can be trusted to convey meaning; the protagonist, Ash, collects words as a way of coping with the confusion they cause her, whilst Arnold’s own inventive literary styling gradually exposes this complex inner mind to readers.

Amy Arnold’s novel Slip of a Fish is an exuberant exploration into whether language can be trusted to convey meaning; the protagonist, Ash, collects words as a way of coping with the confusion they cause her, whilst Arnold’s own inventive literary styling gradually exposes this complex inner mind to readers.

Abbott says there’s no need, absolutely no need, to obsess about words. A word is a word is a word, he says. He thinks it’s funny.

The boldness of this literary experimentation has not gone unnoticed. Slip of a Fish is Arnold’s debut novel, published by the small independent not-for-profit press And Other Stories after winning their inaugural Northern Writing Award for unpublished manuscripts. It has now been nominated for the Goldsmith’s Literary Prize. Slip of a Fish is a worthy contender: original, challenging yet thematically rich, exploring both the mother-daughter relationship and questions of identity and loss.

Ash’s everyday life revolves around her husband Abbott and seven-year-old daughter Charlie, though she is neglectful of motherly duties and social norms, finding interactions with neighbours and acquaintances to be intrusive and fraught with confusion. Over the course of a hot English summertime Charlie begins to withdraw from her mother and Ash responds inappropriately, conditioned by her own past abuses to enact a ruinous event that in turn leads to her own mental deterioration. Although the novel pivots around this unforgivable incident, Ash steers her thoughts away insistently, forcing the reader to circle around the truth with her.

It doesn’t hurt. It doesn’t hurt if you don’t mean it that way.

And it’s OK to be sorry after.

Ash is an unreliable narrator with a perilous vulnerability which is never explicitly referred to but becomes increasingly evident throughout the novel. Her recollections and narration of witnessed events are childlike in the telling despite being adult in context, detailing relationships with her husband and father, an affair with a female yoga instructor called Kate, and the birth of her daughter:

There was pain between my legs, but I wanted to walk up. There was pain where the doctor had stitched. She asked me to slip my feet into stirrups whilst she stitched. That’s what the doctor said. Slip your feet in here.

In this way, Arnold tests the patience of the reader, requiring of us perseverance with what seems to be a confused and, at times, disturbing text so as to reveal the novelty of the prose. Ash becomes progressively locked within a silent world, no longer able to engage meaningfully with external reality; she returns again and again to thoughts of water, swimming, her father, and an impactful sexual experience with Kate. These numerous preoccupations and distractions emerge, repeat, and eventually converge, whereupon the prose evolves from being more akin to first-person stream-of-consciousness towards something newer: narrated but abstracted from time, place, and truth. Ash’s words increasingly overlap and morph in their meaning:

I’m all right getting home. I’ve always been all right. And Abbott’s loosened the rains.

…

Why not walk slowly when the reins are loose because going home isn’t the same.

And where am I off first. I could be off. I could do whatever I did, whatever we did. That summer. Under loose rains.

Much of what felt like essential early detail is discarded along the way, no longer attended to in the text until all that remains is Ash, isolated and damaged, and yet still capable of inflicting harm on those around her. This purposeful paring down of focus, achieved through constant stylistic repetition and obsessive language play, means that the reader is submerged in the character, plunging headfirst into the water with Ash, and from whom it is hard to slip away.

Hannah Whaley

Sounds intriguing!