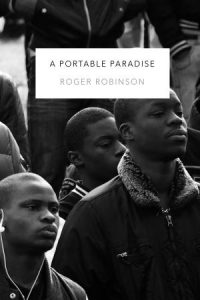

A Portable Paradise (Winner, 2019 TS Eliot Poetry Prize)

In his marvellous essay on writing about 9/11, ‘Can poetry console a grieving public?’, Mark Doty sets out the difficulties of writing about public tragedy. Can one bear witness to ‘the inchoate stuff of experience’ ─ intensely felt private pain or even anger ─ and yet also keep faith with ‘language’s project of discovering and articulating meaning’ which is, of course, the poet’s task as writer?

In his marvellous essay on writing about 9/11, ‘Can poetry console a grieving public?’, Mark Doty sets out the difficulties of writing about public tragedy. Can one bear witness to ‘the inchoate stuff of experience’ ─ intensely felt private pain or even anger ─ and yet also keep faith with ‘language’s project of discovering and articulating meaning’ which is, of course, the poet’s task as writer?

A Portable Paradise is one robust response. Divided into five sections, book’s first section comprises eleven poems on the Grenfell Disaster which circles around the burning tower and its traumatic legacy. In a mixture of prose and poetry, ‘Haibun for Lookers’, there are searing images of confusion, chaos and desperation as Grenfell inhabitants are trapped by the destructive flame racing up the building like a malevolent giant snake, its light ironically mirrored by light of mobile phones from spectators below. In the days after, little gestures and small rituals that the living use to shore up against deep despair are particularly poignant. A daughter brings breakfast, ‘combs her mother’s hair and lays clothes on the bed’; she reads while hearing ‘Umm Kulthum singing about her heart on the radio’. In ‘The Portrait Museum’ makeshift posters capture portrait snapshots from ordinary life; these are ‘flimsy faces of hope for the living’ who ‘refuse this first day of mourning’ ─ but they are gradually blown away. ‘The Missing’ is heart-breaking; the dead are imagined to float,

a conveyor belt of pure air,

slow as a funeral cortege,

past the congregants…

mutter[ing], What about me Lord,

why not me?

But such an ‘airborne pageantry of faith’ is not abstract but built up from a small range of individuals, imagined in all their quotidian diversity. Two simple lines at the poem’s end bring home the mythic power of the Biblical Rapture but reimagined as anguish:

They are the city of the missing.

We, now, the city of the stayed.

Flight ─ literal and metaphorical ─ in black literary culture has a long lineage as is suggested in different places in the collection: the exodus of the migrants to the promise land; three wall mounted wooden birds that are imagined to fly back home in ‘Windrush’; and the baby thrown from the Tower to ‘Catch him Lord!’ brings to mind the legend of enslaved Africans who could fly home.

A Portable Paradise makes concrete and visible the landmarks and icons of a black British presence, and that rich culture and history is especially evident in the middle sections of the collection. If some poems echo Linton Kwesi Johnson’s 1970s poetry ─ angry protests against police violence and civil unrest ─ such resemblances must beg the question of why these scenes are not history. Robinson’s voice wears its vernacular lightly and there is greater formal range: lyric verse, prose poetry, haibuns, haiku-like poems to tonally more performative pieces. However, there is also some unevenness, for example the free association of ‘Prayer’ is perhaps too rawly reflective of the vice-like fear and concern in relation to his son’s health, and one might ask why the Grenfell dead are ‘superheroes’ when their ordinariness enables the bridge to our own mortality. Attentive reading and composting to make connections are needed but these are worth the time and effort. For example, ekphrastic poems suggest a rich thematic seam about the body which take us back to the preciousness of lives in the first section, as well as the fragility of the body as a place you can’t escape from in the collection’s final section. A poem about horses as muscle, blood and bone leads us to think about the whippings, scars and sweat, the ‘Cheap muscle and blood’ that built an Empire.

Yet despite taking us through the emotional wringer, paradise is ultimately a hopeful, transformative place you travel to or hang onto when surrounded by darkness. In ‘Walk with me’, he reminds a young disillusioned black man,

things have move on here,

Brixton is not its history,

and neither should we be

though we hear the call of the past.

This is political poetry worth widespread attention and recognition.

Congratulations upon winning the prize!