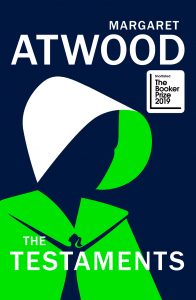

The Testaments

The Testaments by Margaret Atwood, joint winner of the Booker Prize 2019, was eagerly anticipated despite a high bar having already been set by its popular predecessor The Handmaid’s Tale, which encapsulated the potential consequences of suppressing women. The handmaid Offred, in her iconic white veil and red dress, became a symbol of feminism now emulated by red-dressed protestors fighting for abortion rights or for proper recognition of the MeToo movement. Through Offred’s limited narrative, Atwood provided a wake-up call for society to realise how endangered the female identity could become if not empowered with their own voices.

The Testaments by Margaret Atwood, joint winner of the Booker Prize 2019, was eagerly anticipated despite a high bar having already been set by its popular predecessor The Handmaid’s Tale, which encapsulated the potential consequences of suppressing women. The handmaid Offred, in her iconic white veil and red dress, became a symbol of feminism now emulated by red-dressed protestors fighting for abortion rights or for proper recognition of the MeToo movement. Through Offred’s limited narrative, Atwood provided a wake-up call for society to realise how endangered the female identity could become if not empowered with their own voices.

What makes The Testaments so compelling is that it acknowledges the societal changes of this era, and Atwood adjusts her narrative tone accordingly. Multiple narratives of different characters allow the setting of Gilead to be expanded and seen through many perspectives. It is still the repressive regime of totalitarianism that Offred initially introduced us to – however, as Atwood expresses in her blurb: ‘history does not repeat itself – but it rhymes’. Unlike its prequel, The Testaments introduces us to three very different women who are destroying this regime from within. Unlike Offred’s hopeless, defeatist nature of acceptance, these opinionated women plot and scheme their way against the status quo. Due to their efforts, a girl named Daisy is smuggled into Gilead to collect incriminating evidence, to thereby exploit Gilead’s barbaric ways in a global cry for help. Interestingly, Daisy is the only narrative character to be an outsider – she lives in a world sheltered from the misogynistic threats of Gilead, where she is free to form her own opinions and sense of identity. As she passionately conveys, ‘people should stand up against injustice’, and she observes how ‘Handmaids were forced to get pregnant like cows, except that cows had a better deal.’

Having a narrative voice commentating on Gilead’s flaws from the outside opens the reader’s eyes to the sheer horror experienced by the women trapped within. Daisy’s mere existence bursts the bubble of Gilead. She symbolises the freedom all people ought to have, thereby telling readers of the world what Offred never had the courage to say: there is hope. There is life beyond injustice and oppression. She answers the question that Offred felt incapable of answering.

However, readers may believe that we were never meant to find an answer. The mystery behind Offred’s fate in The Handmaid’s Tale has inspired people to determine their own destiny, as feminist activism in recent years has shown. Therefore, by providing an eventual answer to Offred’s dilemma, Atwood has taken that sense of control away from readers – just like the totalitarianism of Gilead, there is always one group or one person in charge of everything, thereby rendering individual hopes and expectations irrelevant. Atwood does this by falling into the tropes of young adult dystopian literature. This genre conventionally portrays a rebellious teenager as the hero who overthrows the ‘big bad government’. Daisy could easily be compared to the likes of Katniss Everdeen from The Hunger Games or Tris Prior from Divergent. Her naïve, raw anger is evidently conveyed through her narration that naturally defies the judgement of her elders – at one point, she ‘stomped off to my room and slammed the door. They couldn’t make me.’

In today’s society, young people’s voices are at the forefront of the news and media, so Atwood’s creative decision to include Daisy as the book’s hero was a relevant and necessary one. However, Daisy would have made a more convincing impact if she was portrayed in a more mature manner, rather than a rebellious, entitled stereotype. Young people are capable of change just like the people that came before them, and deserve more credit.

Leave a Reply