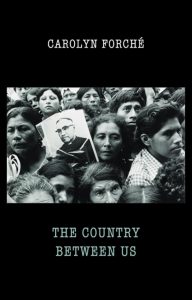

The Country Between Us

There is a cyclone fence between

There is a cyclone fence between

ourselves and the slaughter behind it

we hover in a calm protected world like

netted fish, exactly like netted fish.

It is either the beginning or the end

of the world, and the choice is ourselves

or nothing.

(‘Ourselves or Nothing’)

Journalist, academic, memoir-writer, editor, poet and human rights’ activist, Carolyn Forché’s The Country Between Us, at first glance, would be expected to address her expertise in the last of these roles. Written in response ‘to what she saw in El Salvador in the late 1970s […] as a journalist and while working with Archbishop Oscar Romero’s church group’, unquestionably, it heightened awareness of those abuses to a less aware US public, and it continues to fulfil that witness both there and further afield. However, it is essential to consider that Forché also responded, very successfully, to that civil war in more conventional journalistic ways, so The Country Between Us fulfils poetry’s prime responsibility, which is to language. Forché has refuted the label ‘political poet’, terming herself ‘a poet who is politically engaged’. Those who have come to her work through its very different manifestations (consider, for example, her achievement in Blue Hour) will understand the significance of her insistence. Whilst this is certainly ‘poetry of witness’, and not only of her time in El Salvador, those reading will unpick aspects of the influences of her own Slovak ancestry, her examination of the effect of trauma on language, and indeed the way these experiences have shaped and continue to shape her own humanity. To suggest that this collection stops at being reportage is akin to pigeon-holing Seamus Heaney solely as a wordsmith of The Troubles.

his coffin rocking into the ground like a boat or cradle

(‘Because One Is Always Forgotten’)

However, these poems attack more directly than those in The Tollund Man, for example, being less completely engaged with metaphor. These are poems of great pain, rendered with scalpel-bright sharpness, often graphic, but never gratuitously so. What the Colonel spilled on the shared table can only shock, but that shock is required, and the thread of that horror is picked up to great poetic purpose in the final lines. Here are the things poetry can do, which are not about sensationalism, even when the raw material can hardly be otherwise.

We lie down in the fields and leave behind

the corpses of angels.(‘Selective Service’)

Those lines close a poem which opens referencing a child’s joy in making snow angels. These are all poems of huge humanity, and even the horrific is both contained and detonated purposefully in the care of the lyric. The poet’s love of the intimacies, intricacies and specifics of place not only colours images for those not present, it also builds an understanding of the people behind the atrocities, and allows them a humanity that the best-reported headlines and most accurate statistics cannot. Forché has written at greater length on these matters elsewhere, but her need to understand differently, and succinctly, is clear. There are so many righteous rants out there (and there is a place for the well-honed rant,), but at some point in each of these poems, I cried. They were able to achieve that reaction in subsequent readings. That is something rare.

This then is poetry of the cut of Heaney and Ahkmatova, with the imagery of Márquez; in ‘Endurance’, the speaker is haunted by ‘dead Anna’, ‘her eyes the hard pits of her past’ in a country

where mountains hold the breath

of the dead between then and lift

from each morning a fresh bandage of mist.(‘Endurance’)

Bloodaxe is to be congratulated for re-releasing* The Country Between Us, for though there are sound publishing reasons for doing so, this is an important work, which deserves to come to still-wider attention.

I have come from out cacophonies

ordinary lives where I stood at the sink.

(‘Ourselves of Nothing’)

*(The collection was first published 1981 in the US by Harper & Row, and in the UK in 1983 by Jonathan Cape)

Leave a Reply