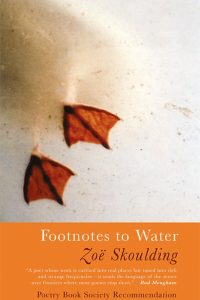

Footnotes to Water

Already a much published and praised poet, Footnotes to Water is Zoë Skoulding’s most recent work. This collection has rivers at its heart: the Adda in Bangor, Wales, where she works as a critic and translator, and the Bièvre in Paris. The mystery behind these hidden rivers bursts forth as language and as a symbol of buried heritage.

Already a much published and praised poet, Footnotes to Water is Zoë Skoulding’s most recent work. This collection has rivers at its heart: the Adda in Bangor, Wales, where she works as a critic and translator, and the Bièvre in Paris. The mystery behind these hidden rivers bursts forth as language and as a symbol of buried heritage.

The collection is divided into three sections: the first, ‘Footnotes to Water’, has poems that delve into the rural and urban Adda, and its coastal connections. The second, ‘Heft’, explores sheep farming, and the third, ‘Teint’ is a previously published collection of poems about a concealed Parisian river. In ‘Teint’ and ‘Heft’ a distinct step-down form is used which creates cohesiveness between the two sections despite the subject matter. In ‘Footnotes to Water’ the forms differ; some prose poetry appears amongst more traditional stanzaic forms. Note how this structural formality allows the weight to fall on imagery and sound:

a river behind itself

this long s disappearing

seriffed into mud or the

torn edges of a map isAdda or Adam after

Cae Mab Adda never

an origin only a

dried up rib of a river [.]

Using sibilance, this opening poem evokes the Adda’s snake-like shape. Furthermore, the rib of Christian creation to depict gender origins suggests its femininity. Skoulding’s poems are packed with metaphors and nuance. References to history ground these intense images to reality, making them more poignant.

Language links the hidden past to the present. The importance of language is demonstrated in a preoccupation with the musical etymology of plants, rivers, and place names, with quotations and Welsh phrases threaded through the poetry. Language achieves, through oral tradition, a memorialisation of the Adda. As a translator, it is fitting that Skoulding asks the reader to translate too, though some of its charm lies in not being understood. Nonetheless, I found the endnotes helpful in revealing the Welsh phrases.

The emphasis on Welsh culture, such as sheep farming, appears throughout, and the second section of the collection, ‘Heft’, signifies the sheep’s innate knowledge of the landscape. Through the motif of sheep Skoulding introduces subtle ideas. Here social structures are discussed:

what wandering did we learn

from the voice that pulls us back

all we like sheep[.]

The phrase, ‘all we like sheep’ emphasises issues of social pressures and conformity and illustrates restriction as the line is pulled back. In deceptively simple lines and metaphor, the poet has the reader engage with, mull, and digest significant aspects of Welsh identity.

‘Teint’ harks back to the history and destruction of rivers out of sight and mind but places it in the different cultural context of Paris. This section is aptly named as the river Bièvre was polluted by the textile industries on its banks: ‘teint’ being the French word for ‘dyed’, echoing our own word ‘taint’. Skoulding weaves French history and philosophy into her poems, with allusions to Rabelais:

Panurge couldn’t charm so

his revenge a river

of dog-desire maddened

by scent the dogs all came

at once they pissed on her

they pissed at her door in

streams of bitter water [.]

The river as refuse is a dehumanising and repulsive image, and Skoulding’s words unsettle the conscience. Death in the river is conveyed through the brutality of skins and ‘scraped shins’. Carmine from beetles bleeding into the water is juxtaposed with the soft, white ermine. Although the lost river can no longer tell its tale, these poems can.

Skoulding’s poems span time and space, giving a depth and complexity that unnerve the senses. Her themes have a rare range, not simply providing a dark view on human greed and destruction but also celebrating cultures and landscapes, lightening the pessimism. Wales infuses her work, an infectious enthusiasm for the country’s heritage and passion for languages. The translator’s ability to bridge cultures makes Footnotes to Water an exceptional collection.

Leave a Reply