Catch and Release

In Catch and Release, place and person meld into one and the same, giving voice to both so that they may reveal how they give life to one-another.

In Catch and Release, place and person meld into one and the same, giving voice to both so that they may reveal how they give life to one-another.

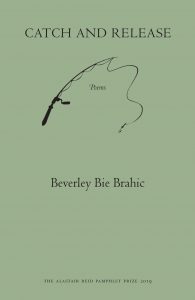

Canadian-born Beverly Bie Brahic has already published a relatively substantial number of titles, such as The Hotel Eden and Hunting the Boar, and White Sheets, which won the 2012 Forward Prize, as well as many translations of French works from writers such as Jacques Derrida and Hélène Cixous. For a pamphlet of free form poetry amongst a span of work as well-recognised and established as hers, the cover of Catch and Release seems neat and unassuming. Whilst the presentation is not particularly elaborate, I find the centralised formatting built around the image of the fishing rod quite appealing. The olive-green colour of the card paper cover reminds me of leaves and grass, but also of a fisherman’s boots, nicely complimenting the image of the rod.

The opening poem, ‘Apple Thieves’, builds on these images of rural nature. Meandering meters and enjambments lead the reader along a small, carefully assembled garden of colour and texture. Brahic builds a little world by placing textured, sounded words such as ‘tart,’ ‘crisp,’ and ‘waxy,’ into the very narration of the poem. From the start, the reader is given a sense of the cohesion of Catch and Release, the strong notion of a self inseparably placed within a living, physical setting.

The reader can trace the growth of this grounded understanding, the space that it can’t separate itself from. In ‘A Shell’, for instance, the enjambed lines twist along short, neat stanzas, a ‘too solid’ structure that ultimately gives the poem its life. Again, so much focus is placed on the texture and pace of words, like ‘exoskeleton,’ which occupies a whole line, forcing me to slow down my reading and feel the confined space that I have been placed within. The poetic device of this work is reminiscent of Marianne Moore’s ‘The Paper Nautilus’, in that they both navigate the shape of a sea animal’s shell. The layout in Brahic’s piece is more restricted, and the metaphors are more grounded in physical objects, but they share an outward movement, a sense that their cadence is working in tandem with their rigid forms to spiral into a conclusion.

Exoskeleton

I pulled from debris

Upchucked by a tideOn my shoreline of memory:

Rain-haunted,

Littered with logs the stormsRip from booms

Southering to sawmills

And lumberyards.

However, not all the poems are quite as confined. ‘Aftermath’ and ‘The Mahabharata’ seem, at least comparatively, far more open. Whilst these poems may not deviate from the short lengths of the other works in the pamphlet, I find that their successions of enjambed lines become increasingly difficult to follow. It takes me several re-readings to pinpoint where the speaker is. I am suddenly lost within this much larger poetic landscape, and it takes me a few attempts to find my way through it. Yet, this does complement the sense of departure and uncertainty that I read in ‘the small silhouette’ among ‘behemoths rerouted’ in ‘Aftermath’.

In ‘Tango’, the last poem of the pamphlet, this loss of scale within the poetic landscape is rendered into an image of the speaker reflected in ‘the silver kettle’s gravid belly.’ Yet, whilst the image is strange and distorted, there is a sense of satisfaction in the speaker’s description of ‘the room in the kettle.’ It is as if the perpetual, conjoined motion of the dance and ‘the sun’ are markers rather than disorientating objects. They have become moving stabilities, changing in pace with one-another. To me, ‘Tango’ concludes the collection not only as its final poem, but as a communion of movement and growth between place and person. Catch and Release serves as a very powerful exploration of this communion.

Leave a Reply