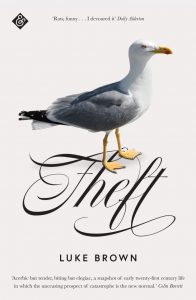

Theft

Luke Brown’s latest novel Theft begins with a tension that won’t let up. Paul’s mother has just died. His sister has gone missing. He’s done something terrible. And it’s also the run-up to the EU referendum. We are hurtling headlong towards some awful reveal. Knowing the Brexit result offers little reassurance.

Luke Brown’s latest novel Theft begins with a tension that won’t let up. Paul’s mother has just died. His sister has gone missing. He’s done something terrible. And it’s also the run-up to the EU referendum. We are hurtling headlong towards some awful reveal. Knowing the Brexit result offers little reassurance.

Except this novel is deceptive. Beyond the first page, the attention-grabbing ploys slow and it evolves into an insightful social commentary cut with enough dark humour to make it spark. Brown has a unique way of writing the urbane into visceral comedic sense:

A street like a Benson & Hedges lit from the end of a Lambert & Butler lit from a burning tub of paint – as English as it gets.

There’s something very ‘emperor has no clothes’ about our protagonist’s blunted gaze as he exposes his pseudo literary life in fashionable London for what it is. Home is an overcrowded flat with no registered address thus denying its occupants the right to vote. Paul writes for the ridiculous magazine White Jesus where he is paid twice as much for his haircut reviews as he is for his book reviews and the photographers ‘boundary-pushing’ concepts unnerve him:

I hoped he would (..) not try to persuade her to (..) pose provocatively on a merry-go-round, or underneath a live swan, or wearing a unicorn horn…

Dealing with his mother’s death and what to do with her house, Paul travels back and forth between London where he now lives and his birthplace in the northwest of England. With large numbers in the north of England voting Leave – much to the consternation of the liberal London elite – he is perfectly placed to shed light on the political and social crisis pulling his country apart. And this is what gives the novel its edge.

The character reflects a demographic ‘schooled in low aspiration’ and denied the spoils of their neighbours where ‘more than wealth marrying wealth, (it) was beauty and intelligence marrying beauty and intelligence’. A self-perpetuating vortex of educational and social deprivation exists, largely ignored by the aspirational few who can afford to worry about how Brexit might negatively impact their lives. On results day Paul and his London friend find themselves caught up in Brexit celebrations in a northwest England pub. When asked the reason for the celebration, they are told: ‘Because we won! We won! There’s more of us than there is of them.’ We are left to realise ‘them’ refers to Paul and his friend – the middle class, privileged southern minority.

Paul falls between gaps: ‘Of the town but not of it’. Living in London but under constant threat of eviction. I notice the urge to put quotation marks around most descriptors of his life; his lack of commitment undermines the authority of nouns. Paul becomes a cipher for unfulfilled white male privilege, highlighting the narrowing effects of class. Hearing that he’s living in London, an old friend comments: ‘You were a bright lad, Paul. I bet you’re earning down there, yeah?’ To which Paul responds: ‘I didn’t like to disappoint them. I just nodded.’ Despite his potential, he remains bound by the confines of his roots.

For all its insistent momentum, there are times when Theft jars. Quite how Paul manages to inveigle himself into the lives of a successful middle-class London family in the way that he does, with his limited charm and often questionable behaviour, is never explained satisfactorily. And suspense becomes heightened to such a degree that the conclusion inevitably fails to fully deliver, leaving us slightly disappointed.

But as the nation wonders at the recent unprecedented surge in Tory support amongst traditional Labour strongholds in north England, Theft feels particularly relevant and significant. Paul’s is the perfect voice to add to the current political discourse. And he’s so funny, we can forgive him for (almost) anything.

Leave a Reply