Essay fragments by Liam Wright

Displaced

Drifting through a little hall of renaissance pieces, the frames of gold, green and grey only hold me briefly. There, on the left-hand side of the gallery from the entrance. Untitled, 1975. Four or five brush strokes create a curtain-thick concrete wall of translucent paint. Over it, a spill. Deeper black, latching on with both of its wispy filaments, almost-arms, and billowing into a dense curtain.

Untitled, 1975 by William Johnstone looks like an error. Not that it is a bad painting, simply that it is the depiction of impossibility. It sits so heavily within its contained, off-white universe, only taking up about a fifth of the frame. Ali Smith might suggest that ‘it’s made out of the flatness of its own surface,’ and she would not be entirely wrong, but it does not do so ‘so we’ll know we’re not being deceived.’ It veers even in its own form, refusing to look settled in its two-dimensional plain definitely remaining within it. Its rectangular brush strokes give it a constructed appearance, yet the black spilling off to the right shifts under my eyes, granting it living movement.

Untitled, 1975 by William Johnstone looks like an error. Not that it is a bad painting, simply that it is the depiction of impossibility. It sits so heavily within its contained, off-white universe, only taking up about a fifth of the frame. Ali Smith might suggest that ‘it’s made out of the flatness of its own surface,’ and she would not be entirely wrong, but it does not do so ‘so we’ll know we’re not being deceived.’ It veers even in its own form, refusing to look settled in its two-dimensional plain definitely remaining within it. Its rectangular brush strokes give it a constructed appearance, yet the black spilling off to the right shifts under my eyes, granting it living movement.

I can’t decide if this painting is alive or dead. It can’t seem to either. Not like with Schrödinger’s Cat, where I can’t tell so long as I can’t see it. I can’t tell because I’m seeing it. I’m floating along with it now, taking up space, lurching back and forth into opposite ends of uncertainty, too absorbed to feel any weight in my body.

*

Born to a Scottish farming family in 1887, what was it that pushed Johnstone towards the abstract? His time spent in Paris gave him an understanding of modernist art practices, a style typically characterised by ‘a rejection of history and conservative values (such as realistic depiction of subjects),’ as well as ‘innovation and experimentation with form’ and ‘a tendency to abstraction.’ There is the unmistakable shape of the industrial in so much of Johnstone’s work. Straight lines and sharp edges painted in black. Yet these shades, these forms, I also see in the real Scottish Borders and Highlands, places that are usually associated with wildlife and wilderness. Johnstone studied First Peoples’ cave paintings ‘deemed naïve.’ These labels smack of cold, colonial detachment from a world we all must share. From everything I have read about his work, his life, his travels, I like to think Johnstone recognised this deadly contradiction. I sense how, with his farmer’s boy-eyes, he depicted our self-inflicted loss.

A lie. There used to be miles of forest in Scotland, populated by more than just the occasional stag. These lands used to be walked by wolves, hundreds of years ago. Then the forests were mostly raised. Home was made alien for generations, just as it was in most of western Europe and, centuries later, North America. As any one of us Johnstone had as little choice but to be a part of this disruption. It seems obvious to me that he would roam for so much of his life. And he did. America, London, Paris… He travelled all over, though not always as a practicing artist. Perhaps he kept moving because nowhere was quite home; maybe he shared this sentiment in his work, so that others could connect. After all, he was a teacher for much of his life, including during World War Two, a time when home meant death for so many. Johnstone did not paint then. He spent the final years of his life back at the Borders, painting and farming. Perhaps he did have a home. He may have found a comfort, at the very least.

As I look at his works, I keep seeing shapes, colours and faces even I, a non-native, recognise of the Borders.

*

The black blotch may start to spill out. The thin limbs might start to extend further, out of the frame. Breezeblock walls of wispy black could begin to cover the walls of the gallery, creeping into the other paintings. They could cloud the entire upper floor in a dense mist of galaxy-black paint, dragging me within it. It might seep further, submerging, absorbing the whole of the McManus, and I could drift along in its paper-thin depths. I might make a home from the unknown, drawn by its semblance of familiarity, like a puppet letting itself be pulled along by its last remaining thread.

The black might propagate, casting Dundee, then Angus, then the east coast, then the whole of Scotland in a sloshing wall of onyx. Then, its misty roots would cloud over the Antarctic as its river-branch-limbs grasp the north pole, absorbing everything in between in its slate-mercury whole. And it could reach further, finally inhabiting the one place it seemed to belong, submerging the galaxy. Then, I would lose myself, becoming part of a whole I would have lost the ability to try to understand. Too scattered to be myself, to be a self, but floating through the universe, never attached to belonging, always moving.

But I don’t. No movement, no expansion. The painting is still on the wall. I notice a little splash of red on the canvas, mostly obscured. It reminds me of my place in front of the frame, the solid, finite space I occupy in the gallery.

I take a picture, for reference. Then I leave.

*

Composite Soldier

John William Kimber, born 1875, died 11th of May 1918. He points up from his neatly unfolded family, an awkward, stiff-backed, black-dressed pistil of a regal white lily. A wife and three children, none of the latter seem like they are any older than eight.

I spread the blooming fractal of once-life, whole, kaleidoscopic, across the table. Sincerity spiders across the page in all its rushed errors, legible anxieties. These are the words of someone inescapably bolted to death, a fragility made firm in front of my eyes.

I recognise Arlette Farge’s remarks—’surplus of life that floods the archive and provokes the reader, intensely and unconsciously’ on the brink of a death. This is more than a subconscious effect though. I knowingly feel the growing weight in the pit of my gut, the sorrow for a human being, a whole family, I would never know.

The letter is dated in the in the top right corner. 1/5/18.

Golden buttons and buffed bayonets shine through the grainy murk. Blurred faces glance sidelong at me. One of the greyed marchers, ‘the most capable officer attending the class,’ is looking over. The slight lighting-up of his face, the distinct slant of his eyebrows… Yes, that must be Jack.

Despite the shine, I read the same sullen, anxious expression in his face and in his fellow marchers. Do they know? Perhaps I’m placing what I know in a time and place where it doesn’t belong.

John William Kimber. Alive in a time, dead in the next. Existing in both.

*

Window to The Monochrome

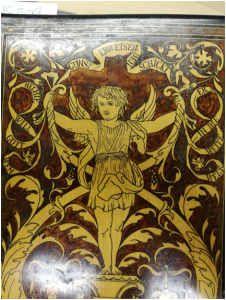

‘Wem Gott will rechte gunst erweisen den schickt er in die weite welt.’

The words, only some of which I can identify, weave over and under one another, forming an intricate arch on the top half of the cover of the gigantic tome. The cherub held up by two big fish on the front cover, drawn in a manner reminiscent of medieval bible calligraphy, holds the promise of vast, ancient scrawls. ‘God, who wants to show the right favour, sends it into the wide world.’ (Thanks Thomasin.) Well, if you say so.

I feel a slight strain at the root of my index as I pry the cover apart from the first page. No giant, biblical scrolls, or even any bored monk’s calligraphy, but photos. Most of the volume’s size comes from the bulkiness of the pages, which are almost as thick as the cardboard on a delivery box. Most of the book is empty.

Black and white. A duck pond, a restoration period castle with an old steel bridge beside it, men in top hats. . . Remnants of times that meant something to someone, but nothing to me. Some of the pictures are captioned with brief descriptions in pencil, but because of the handwriting I can’t tell whether they are written in English or in German.

Yet, here and there, suggestions slither into the air between the page and my eyes. I can just about extract the words ‘wald’ and ‘weg,’ forest and path, from one of the brief descriptions. But then I am thrown off track by text that seems to say, as far as I can tell, ‘men in the snow,’ in English. A family? Certainly a wealthy one, if that’s the case. It would help explain the picture of the duck pond standing out a fair bit, in that, compared to other photographs seems just like scenery I don’t have a structure with which to interpret these photos. I have no narrative.

Susan Sontag details that ‘photographed images do not seem to be statements about the world so much as pieces of it, miniatures of reality that anyone can make or acquire.’ Narrative is not inherent, it is the covering placed upon an object. This small collection of images was naked. Unfortunately, these photos are fragments of a world that I am not familiar with. I have been dropped in a vast, bright paper ocean. I continue to drift.

I feel toyed with, in a way that I can’t help but respond to. A wry smile pulls at the corners of my face and the lower lids of my eyes. There is character, laced in between the many layers of the thick pages, over and under the pictures, but it darts and veers away from my reaching understanding. It’s there, but only as a silhouette. I recall Rusty Morrison’s piece about how poetry ‘[lifts her] out of understandings that have held [her], contained [her] in ways [she] hadn’t understood.’ I feel the same way now. I am strung up from my head above understanding, relishing my attempts and failures at trying to grasp at it. It so close, so clearly there, but it remains unattainable.

It is like trying to clutch clouds of dust suspended in sunlight. I am enraptured by particles of beauty into an impossible task. I find a joy in irresolution. Now that I know that the album was a collection of photos taken in and around Braunschweig, northern Germany, I feel like I have shut myself out of a whole world, an unknown space in my own mind, forever.

People are beginning to pack up their own little artefacts. Time is up. Gently, I close the heavy cover.

*

Monkey in a Jar

At times, you can forget that you’re looking at something that was once life. Crocodile skulls made into complicated conversation pieces, mice in formaldehyde vials. . . It’s a reminder of motion. Ghosted growth.

Not that isn’t fascinating to see everything displayed neatly around you. There is a certain beauty in that, rolling eyes along carefully placed shelves and display cases. . . like marbles in a Rube Goldberg machine. It’s quite easy to get pulled along by the ring of the room, the weirdness of a skeleton you can’t quite identify from this distance, the constant, slight shine of a glass eye directly beneath a lamp. . .

Life just out of mind’s real reach. Perceptible, but unattainable.

Cages of firm glass, old oak, and straw ribs keep the museum’s specimens from ever wandering into your open mind intact. You may spy fragments, loose limbs and bisected shells from a distance, but they never quite add up to anything whole from up close, buried in their cages of crafted clarity. Despite this, they call to you, in a sense. They are ‘disclosing themselves as dead stuff,’ Jane Bennett might claim, and that is because they are also implicitly ‘disclosing themselves as live stuff.’ If you look for long enough, you can’t help but imagine the male huia cock his head as he stares at you, or the rhino beetle snap its faintly-shining wing covers up in preparation for take-off. They don’t, they won’t. But they could live, they could use their millennia-arranged forms.

You can’t forget they once did.

*

© Liam Wright

Notes:

1. ‘it’s made out of the flatness of its own surface. . . not being deceived’: Ali Smith, ‘Green’, in Stephen Benson and Claire Connors eds, Creative Criticism (Edinburgh: EUP, 2014), p. 251.

2. ‘a rejection of history and conservative values (such as realistic depiction of subjects)’. . . ‘innovation and experimentation with form’. . . ‘a tendency to abstraction.’ William Taylor Fine Art, ‘William Johnstone OBE (1897-1921)’, ‘Biography’. <https://www.richardtaylorfineart.com/gallery/contemporary/william-johnstone-obe/scottish-abstract>, [accessed 11/10/2019].

3. ‘deemed naïve’: Ibid.

4. ‘the most capable officer attending the class,’: John William Kimber papers are from UR-SF 71, John William Kimber Collection, University of Dundee Archive Services.

5. ‘surplus of life that floods the archive and provokes the reader, intensely and unconsciously’: Arlette Farge, The Allure of the Archives, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), p. 31.

6. ‘Wem Gott will rechte gunst erweisen den schickt er in die weite welt’: album and photographs are from MS 304 McKean photograph album, University of Dundee Archive Services

7. ‘photographed images do not seem to be statements about the world so much as pieces of it, miniatures of reality that anyone can make or acquire’: Susan Sontag, On Photography (London: Penguin, 2014), p. 2.

8. ‘[lifts her] out of understandings that have held [her], contained [her] in ways [she] hadn’t understood’: Rusty Morrison, ‘She Encouraged the Separation: Poetry and Gravity’, Kenyon Review 34(2), (2012), para. 20.

9. ‘disclosing themselves as dead stuff’. . . ‘disclosing themselves as live stuff’: Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), p. 5.

Bibliography:

William Taylor Fine Art, ‘William Johnstone OBE (1897-1921)’, ‘Biography’. <https://www.richardtaylorfineart.com/gallery/contemporary/william-johnstone-obe/scottish-abstract>, [accessed 11/10/2019].

Ivy Stanmore, ‘The Disappearance of Wolves in the British Isles,’ Wolf Song of Alaska <https://www.wolfsongalaska.org/chorus/?q=node/230 >, [accessed 11/10/19].

Acknowledgements:

Images from the John William Kimber Collection and McKean photograph album appear courtesy of the University of Dundee Archive Services.

The photographic image of the D’Arcy Thompson Zoology Museum appears courtesy of the University of Dundee Museum Services.

(Ed— Liam Wright is a Year 3 English and Creative Writing student; these are excerpts from his end of semester Creative Essay submission.)

Leave a Reply