Essay Fragments by Kristyn Leonard

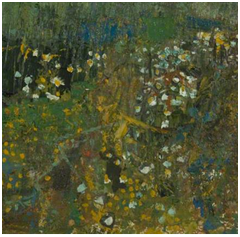

Corn Feverfew III, 1960

You have to search to find this painting. In a gallery full of large pieces and overbearing color, it takes a backseat. Its message is dulled, pushed down, overpowered by others. The greens are smeared with brown and gray, highlights few and far between, yet the more you look, the deeper you sink. Suddenly, you’re knee deep in the paint, in the mud. Mucking through the speckled flowers and flat grassy hillsides you find the dimension.

What the visual effect of this painting might lack in precision, it makes up for in sheer amount of paint. Reflected in the layers, the time it takes for the oils to dry before the next color can be applied, this art took care. Joan Eardley painted this from her own cottage. She looked out over the fields and watched them change. It’s a change that’s tangible in the work. Layer after layer reflect what was found there one day, then the next. There is care in this painting. A love of home. It is busy up close, maybe packed with the familiar.

What could you bear to leave out of a representation of home?

As the painting extends, the detail fades, leaving space for the unfamiliar. You step away from the frame, bit by bit. Backwards towards mountains; East or North or whatever cardinal direction takes you into the white wall of the gallery. Ridges form into landscape, smears of green and brown and splashes of white become the horizon that was not at first visible.

In the smear of yellow in the bottom center, or, slightly off-center, I can see a silhouette. The sleeves of a yellow raincoat stretched out―a little girl catching her balance as she plays in the mud and the grass, prancing through the flowers on a rainy day. It’s very likely that she’s not there. That this dash of yellow is a part of the corn or the daisies.

But why do I see her so distinctly?

The mounted text next to the painting tries to place you outside the frame, overlooking the landscape as the artist did, but that’s not where I am. I am in that smudge of brown topped with the yellow cross, the outstretched sleeve, reaching to pluck a flower from the feverfew.

The mounted text next to the painting tries to place you outside the frame, overlooking the landscape as the artist did, but that’s not where I am. I am in that smudge of brown topped with the yellow cross, the outstretched sleeve, reaching to pluck a flower from the feverfew.

As she takes a step forward

my imaginary girl

so do I.

*

The Art of the Forty-Minute Dramedy

When I write about the people in my life, I like to give them the names of fictional characters. It makes the writing easier somehow. There are fewer consequences. Lately, I’ve been renaming the boys I love and have loved after the boys in Rory Gilmores life.

My Jess is easier to write about when he’s Milo Ventimiglia in my head.

Maybe sometimes it’s also easier to write about myself if I can pretend I’m Alexis Bledel.

I don’t always like myself in the stories I choose to tell on the page. It’s nerve-wracking to write non-fiction, to have to give yourself that much thought. Of course all writing represents the self to some extent. We reveal aspects of our own history, our culture, and our experiences with every word that we write, be it fiction, non-fiction or poetry; Carl Klaus observes, ‘In some sense, of course, the voice in a personal essay does put one in connection with its author, more directly and closely than any other form of writing, except a personal letter’.

I don’t know if the “I” on the page is really me.

I don’t know if the “I” on the page is really me.

That’s a lie. I know she’s not.

But, I don’t know how much we really have in common. Klaus describes how the essayist creates their own voice, something that ‘is both an authentic and a fictionalized projection of personality, a resonance that is indisputably related to its author’s sense of self but that is also a complex illusion of self’ (47). Part of it is deliberate then, sure. I choose whether “I” will be victim or villain in the story I tell. I spend hours mulling over word choice and turn of phrase, deciding whether “I” will be charming or tongue-tied, flippant or reflective. Embarrassing or dense or vapid or even downright cruel.

Yet it feels like there must be something more, something innately me that comes out when I write. Some things I write I know sound more like me than others. Maybe those others are the pieces where I start to feel a little more like a Gilmore Girl, when the neon of Las Vegas starts to transition into the glimmering string lights of Stars Hollow.

Because deep down I know that Klaus is right and anyone who reads my work will feel a ‘human presence’ in it (46). I know they will read my name as the author and begin to picture a person, and wouldn’t it be easier if that person wasn’t the real me. If I could convince myself that when they read my work and they thought

she’s embarrassing

she’s dense

she’s vapid

she’s cruel

that it wasn’t really me they’re judging. Sure, it was my actions, my thoughts, my hopes, my fears.

But “I” isn’t really me if she has long dark hair and wide blue eyes. Not to me, anyway. And who else am I writing for in the end?

*

An American in Dundee

Crossing the street is not a skill. It should not be something you are good or bad at. Yet, here I am, struggling. You don’t realize how vital such a mundane activity is until suddenly the entire action has been flipped.

(You drive the wrong way here. Your cars are weird and mirrored, your driver sits in the incorrect seat, and you drive on the wrong side of the road.)

My mom taught me to cross the street holding her hand. There’s a system to it. Left, right, left. Cars coming from the left are closer to you. You check for them twice. I moved to Texas, a world of one way streets and I learned the ritual of which way to look. One street left, one street right, one street left. Alternating. Left, right, left. Crossing with headphones in, while talking with a friend or in the middle of writing a text, I was competent, I was skilled.

And then I moved to Dundee. Being an American in Dundee is a strange experience. It’s different from when I visit Edinburgh where you run into Americans on every street. I feel more like an oddity in Dundee, no one seems to understand why I ended up here. I’ve been told multiple times that I am the first American many people have met in this city.

And then I moved to Dundee. Being an American in Dundee is a strange experience. It’s different from when I visit Edinburgh where you run into Americans on every street. I feel more like an oddity in Dundee, no one seems to understand why I ended up here. I’ve been told multiple times that I am the first American many people have met in this city.

This seems strange to me because Dundee does have connections to the US. (Oh, that’s another thing. I say, ‘I’m from the United States or the US. People here say I’m from “the States”.’)

Historically, Dundee has had a direct trade relationship with the United States. As of 1830, ships were regularly carrying Dundee exports such as twine and stockings to the US and Canada. This relationship continued through the American Civil War, where Dundee was one of the few ports to successfully export goods to both the Union and the Confederacy. The fact that they maintained these relationships meant that exports of items such as cotton boomed during this period and lead to major economic growth for the city.

(This was something that was explained with a strange pride in lecture. I think it’s important to note that many ports ceased trade with the Confederacy during the American Civil War because the South was fighting for the right to own slaves. Maybe it’s not a sign of diplomacy and trade skill that Dundee continued to support these efforts.)

Even today, Dundee is connected to the United States through a twinning association. Dundee has four twin cities around the world and one of them is Alexandria, Virginia, USA. The Twinning Association programs are meant to promote tourism between Alexandria and Dundee, so it seems strange that there aren’t more tourists here because of that.

(Then again, I’m sure Las Vegas and Denton both had twin cities, and I’m sure I never even heard about them.)

Writing this, I only have five more days as an American in Dundee. I only have five more days of struggling to cross the street and looking both ways approximately fourteen times to make absolutely sure no one is coming.

I think I’m going to miss it.

*

“…studies of travel writing—written representations of journeys and experiences away from home—form a distinct but eclectic body of critical scholarship that helps us to understand relationships between places traveled from and places traveled to”

Karen Morin, “Geography and Travel Writing,” 2006

On the Fourth of July we would always go to the big park by our house, the one they used to let dogs in but don’t anymore. Every year we went, bringing along snacks and picnic blankets. We would sit on the grass, in the shade for hours until night fell. When the bright blue sky faded to black, we watched the fireworks while God Bless the USA played. My mom always cried.

We always walked to and from the park, walking there in sandals with freshly washed hair. We bounced and ran, bolting ahead of our parents to the corner of each block before waiting patiently for them to walk us across the street. We ran from the heat, jumping between the shade of the trees that lined the sidewalk. Even in our flip flops, our feet burned. Heat is inescapable when it’s 116 degrees Fahrenheit outside. The ground soaks up the sun, and if there is no shade, the asphalt can melt through the soles of your shoes.

At the end of the night, we would walk back barefoot in the dark, hair pulled away from our faces. It was an impossibly long walk. Longer, by far, than the walk there had been. The warmth of the air sapped our energy as we padded along, the concrete burning our feet. Even in the darkness we felt the heat. We hopped at every little shadow on the ground, afraid of the roaches and crickets that were taking advantage of the sunless hours.

That walk, that annual pilgrimage for hot dogs and fireworks, is all I can think of as I now wander through the dark in the city of Dundee, placing all of my trust in my roommate who leads the way. And google maps of course. We are going to the big park, going to stand in the grass and watch the fireworks on bonfire night. It’s strangely familiar but also entirely alien. I don’t know what music will be playing; my mom is eight time zones away, and it’s only 5 degrees Celsius, a temperature I find completely unbearable.

It’s the fifth of November, and tonight we are walking to and from the park, walking there in boots and sweatshirts, hair tucked away under hats. We laugh and meander, hoping that if we follow the group of girls bundled up and speaking loudly with decidedly Scottish accents we’ll get where we need to go.

It’s the fifth of November, and tonight we are walking to and from the park, walking there in boots and sweatshirts, hair tucked away under hats. We laugh and meander, hoping that if we follow the group of girls bundled up and speaking loudly with decidedly Scottish accents we’ll get where we need to go.

None of us are familiar with this place. We’re all here on exchange for the semester, living in Dundee on some strange extended vacation. As we walk farther through the cold, cobblestone streets, we join a crowd. We walk alongside families pushing little ones in strollers, the children wrapped in blankets. The older kids push on ahead, stuffed into their bulky coats, scarves tied tight around them.

Suddenly I feel as though I am intruding, intruding on a future memory, on a family tradition. Intruding on a holiday that I don’t really understand, pretending to be a part of this community that I’m only vaguely connected to.

Suddenly, I am highly aware of the horribly unfamiliar streets. The familiar browns and tans of home, the rocks and the desert landscaping, the perfectly blue sky and the wide asphalt roads are replaced here. The buildings are too tall and the streets too narrow. Walls and windows tower overhead, the grey roads matching the grey buildings matching the grey sky.

I have been in Dundee now for months, I have walked these streets, become familiar with my routes, with my flat, with my pubs, and with my friends.

And at once I am aware of how unaware I have really been. I have been on vacation here, staying here like a tourist. I don’t live in the town. These places are not mine. They could be one day if I spent long enough in them, but I haven’t, and I most likely never will. The stories I tell about this place, the way I represent it when I go back home will always be shallow and inadequate compared to the people who settle here, who live real lives here.

I will never be able to tell the story of Dundee like the children who pass by me, on their way to the park for Guy Fawkes Day.

They run through the cold, jumping across uneven stones as they carry on cheerfully down the sidewalk, and, at the end of the night, they will walk back through the dark, clutching light up wands in their hands, and it will seem to them like an impossibly long walk. Longer, by far than the walk there had been.

© Kristyn Leonard

Notes:

More information on Dundee’s connection to the American Civil War can be found in David Carrie, Dundee and the American Civil War, 1861-65, Abertay Historical Society Publication 1, 1953 <https://abertay.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/DundeeAmericanCivilWar.pdf>

- ‘In some sense, of course, the voice. . . except a personal letter’: Carl H Klaus, The Made-Up Self : Impersonation in the Personal Essay. University of Iowa Press, 2010; p. 46.

- ‘is both an authentic. . . a complex illusion of self’; Ibid., p.47.

- ‘human presence’: Ibid., p.46.

- ‘studies of travel writing. . . places traveled from and places traveled to‘: Karen Morin, ‘Geography and Travel Writing’ in Encyclopedia of Human Geography edited by Barney Walf. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications (2006); p. 503 – 504.

Bibliography:

Carrie, David C. and Abertay Historical Society. Dundee and the American Civil War, 1861-65 / David C. Carrie. Abertay Historical Society Dundee, 1953.

Klaus, Carl H. The Made-Up Self : Impersonation in the Personal Essay. University of Iowa Press, 2010.

Morin, Karen. ‘Geography and Travel Writing’ in Encyclopedia of Human Geography edited by Barney Walf. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications (2006); p. 503 – 504.

‘Understanding the Drying Times for Oil Colour’, Winsor & Newton, http://www.winsornewton.com/uk/discover/tips-and-techniques/oil-colour/understanding-the-drying-times-for-oil-colour.

[Ed – Kristyn Leonard was an exchange student from the USA. This is an excerpt from her 2019 autumn semester Creative Essay submission.]

Leave a Reply