Secrets found in the deep by Thomasin Collins (Winner of the 2020 PNR prize for Creative Essaying at the University of Dundee)

‘The story opens when I go to the gallery with you.’

‘The story opens when I go to the gallery with you.’

I walked in with you. We were chatting, but I was only half-listening. I was distracted by the sculptures in the cabinets and the brightly painted mural on the wall. They faded behind me as we continued to walk and as I stepped up onto the stairs. The stairs were a geometric piece of architecture so at odds with the imperfect havoc of hand-made creations coaxing us closer. As soon as my feet lifted off the last step, I glided into the exhibition room, and was slapped in the face by orange and pink canvas. I abandoned all pretence of paying attention to what you were saying. That painting was fast and bright, but I needed to find something that I understood with one glance without actually knowing anything at all. I made the rounds. I was unfair to all the other pictures in the room. I refused to see any other after I spotted the familiar shape of a Will Maclean print.

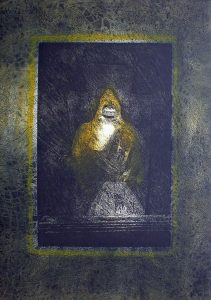

The subject was boxed in with colour, deep and full. Greens poured from its boundaries, swirling and twisting, colliding with the sea’s shivering dark. A printed net floated in the frame. True to the nature of the sea’s surface, the net was not tranquil in its floating. It snagged and dragged, yanked aboard the vessel, breaking through our fisherman’s safe yellow box. That yellow. It is the yellow at the heart of daisies you chained, gifted around my neck. But this yellow was no gift from nature. It is industrial and unforgiving, like on black and yellow safety tape. It is only overthrown by the soft green of the sea’s depths. Our subject inhabits that yellow, they are forged of labour, toiled. We see an oilskin in action.

When I used to think of an oilskin, I pictured the velvet of seals, their wet sheen light against rocks in the sunlight. Now they hint at knives and nets, hooks and traps, masks and armour.

*

You know I don’t read paintings the way you do, I see them like stories waiting to unfold. To me, they are suspended. I’m trying too hard to reveal the tale. But there are always hidden snippets in a Will Maclean print and I will have to return over and over to see them all. It’s like reading a Poirot and finding out who the killer is, but not why or how, and having to reread it for clues. I see writing but I can’t make it out. Is that a visor underneath the hood? Is it a boat instead of eyes? Why the unusual shape behind the subject’s head? I turn away and hope that if I whip my head round quick enough to have another look, I will have caught it in the act, and it will have let slip one of its treasured secrets. But nothing changed and that chest of secrets remains locked under those green depths. To find the chest you must read the poem.

I saw boats and fisherman

dancing on the sea.

Now I remember another set of stairs, not as regulated and mathematical as those in the McManus. These are my mum’s stairs, they were built with the house in 1907, and the banister leans slightly at the bottom from years of human weight. At the top, to the left, there is a massive print. I remember what it was like, this summer, to help hang that print. I had to lean over the rails and hold the weight of the frame as Mum stood on her stool as she, carefully, slowly, lowered the string onto its hook. Stepping back and assessing our success, adjusting it on the left, straightening a little to the right, the whole house came together instantly. It fit in to our space.

Time, skill and effort bores its way through the wallpaper in that house, with picture hooks and nails. For my mum it is a labour of admiration, not just decoration. Now empty walls discomfort me, the negative space hides more than it reveals, and it is cold. Whenever I moved, the art came too, familiar scenery and figures following us to the new house. Unpacked from bubble wrap and rehung, their colours and light reflected cultures and stories back at me in the strange darkness of a new corners and staircases. When a new addition arrived, it became part our story, part of my familiar picture.

My mum relishes Will Maclean’s work. She collects his work. She sells his work.

*

I saw you at my mum’s gallery in Inverness last year; there was a chatter at the front desk, a regular had come by to say Merry Christmas. The print screens clicked, tapping against each other. Light glanced off the plastic as the wing opened like a book, revealing the blue, yellow, green and black pages. The wing was heavy when it was lifted free of its notches, the burden a strain on my arms. Letting out a whoosh, the sheet slid free of the metal frame. I heard the printer rumbling to life, and a Will Maclean CV come shuddering out on cream paper. It slid next to the print, wrapped in tissue and secured by sturdy cardboard. I gave it to you in a red bag and off you went. I doubt you’ll read it.

I saw you at my mum’s gallery in Inverness last year; there was a chatter at the front desk, a regular had come by to say Merry Christmas. The print screens clicked, tapping against each other. Light glanced off the plastic as the wing opened like a book, revealing the blue, yellow, green and black pages. The wing was heavy when it was lifted free of its notches, the burden a strain on my arms. Letting out a whoosh, the sheet slid free of the metal frame. I heard the printer rumbling to life, and a Will Maclean CV come shuddering out on cream paper. It slid next to the print, wrapped in tissue and secured by sturdy cardboard. I gave it to you in a red bag and off you went. I doubt you’ll read it.

Mum shows her prints and talks about them to anyone who will listen, waving her arms in great swoops, like she was there when they were made. I listen. He anchors much of his pieces in is heritage, and poetry accompanies some of them. Some of his work is created because of poetry, or the other way around. You cannot differentiate between ‘Dancers’ and Angus Martin’s poem, they are cut from the same piece of cloth. Both men come from fishing backgrounds, before the destruction of herring-fishing. The ‘Dancers’ not only reminisces about the old ways, but of Maclean’s old ways. The print alludes to a painting of his from 1989 called ‘Skye Fisherman: In Memoriam’ and Martin reminds us that fishing was a ‘greater dance’, a life force of the Highlands.

But I watch for your gull-haloed coming.

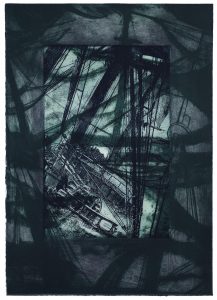

From Will Maclean, Scottish history imprints its mark and speaks from deckled paper. Tributes are made to the families who fled the clearances, to black houses, the creels and bait, and the smog of peat fires and to a ‘night of islands’. Opposite my mum’s huge print is my favourite artwork in the whole house. It is called ‘Adam’s Clan’ and it is another of Maclean’s. The ship is bordered in; it’s like looking through a viewfinder on a camera. The sheets and cleats lash out into the periphery of my vision. It’s chaos. The lines criss-cross, and I don’t know what they mean, they confuse me, smother me. Those lines seem off, that beam does not belong there. It should not bend. The ship is tilted at an unforgiving angle, but the mast remains straight. The irregularity is nauseating, as the ship has surrendered to the sea’s thunderous roll.

From Will Maclean, Scottish history imprints its mark and speaks from deckled paper. Tributes are made to the families who fled the clearances, to black houses, the creels and bait, and the smog of peat fires and to a ‘night of islands’. Opposite my mum’s huge print is my favourite artwork in the whole house. It is called ‘Adam’s Clan’ and it is another of Maclean’s. The ship is bordered in; it’s like looking through a viewfinder on a camera. The sheets and cleats lash out into the periphery of my vision. It’s chaos. The lines criss-cross, and I don’t know what they mean, they confuse me, smother me. Those lines seem off, that beam does not belong there. It should not bend. The ship is tilted at an unforgiving angle, but the mast remains straight. The irregularity is nauseating, as the ship has surrendered to the sea’s thunderous roll.

The wind blows the sails like ghosts across the paper, crowding my sight, it’s too blurry, fuzzy, wavy. There are details to be found in the pleats in the ropes, the knots in the wooden railing, they catch my eye as I seek for a bigger picture, the secret. It dawns on me, those are not ropes hanging from the boom, they are limbs. Clenched, clinging on in the gale. Shadows of men cluster at the bow, crowded, fleeing to the farthest edge from the water. They leave the safety boats abandoned in the middle. Only a few remain, persistent against the inevitable, sprayed with freezing brine as they work against time. It is all so green, a blue green, disturbed by the etched black ink, summoning frantic desperation for the shipwreck in the storm. The green deep is no longer soft. It excites me and terrifies me. It reminds me of the Iolaire.

It’s as though the wails of widows and mothers and sisters can still be heard from the Beast of Holm, where Maclean marked the centenary of the tragedy of the Iolaire with a gut-wrenching, simple sculpture. A cast bronze rope tidily coiled around itself, sitting, as if waiting to be put to use. There is a story about the rope that you and everyone in Lewis knows. A strong swimmer, John Finlay Macleod, dived into the ferocious green and struggled against the swell to tow a rope to the rocky shore. He brought many men home with him, as they clung onto the rope, dragging against the waves, heaving their lungs above the water, a lifeline. He saved 40 of the 79 lives that survived that night, before the rope snapped. But Maclean’s sculpture waits safely onshore. We saw it revealed by the Lord of the Isles, to commemorate more than 200 souls that, still wearing their British uniform, never made it home to their families on New Year’s Day, 1919. Instead, Stornoway woke to find their loved ones washed ashore.

All this going on as I stand by your side and you blether about you weekend plans, my eyes awash with green and yellow the bright gallery in the McManus. In the islands it was the sea on which they thrived that hurt them the most. We leave, walking past families and strangers here to see the exhibition, back down the rigid staircase. Clusters of conversations disperse through the hall, but I am silent, thinking only of home.

Notes:

- ‘The story opens when I go to the gallery with you’: Ali Smith, ‘Green’ in Creative Criticism, ed. by Stephen Benson and Clare Conners (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014) p. 250

- ‘I saw boats… on the sea’: Angus Martin, ‘Dancers’ in A Night of Island (Nottingham: Shoestring Press, 2016)

- ‘greater dance’: Ibid.

- ‘But I watch for your gull-haloed coming’: Ibid.

- ‘night of islands’: Ibid.

© Thomasin Collins

[Ed – Thomasin Collins is a year 3 English and Creative Writing Student. This piece was developed from her end of semester Creative Essay submission. The exhibition that Thomasin Collins visited, ‘As We see it’, was staged at The McManus Gallery Sat 23 Feb 2019 – Sun 8 Mar 2020. The etching by Will Maclean, ‘Dancers’ is made from a suite of 10 etchings he made titled, ‘Night of Islands’ inspired by Gaelic poetry and prose. Angus Martin’s poem’s ‘Dancers’ was originally published in The Larch Plantation (1990) and published again in A Night of Islands (Shoestring Press 2016). Quotations from the poem appear with the kind permission of both Angus Martin and Shoestring Press.]

Leave a Reply