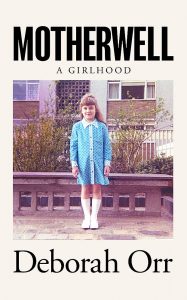

Motherwell: A Girlhood

Motherwell is a poignant family portrait, articulately painted by the late Deborah Orr of a life with ‘house-proud’ mother Win and ‘factory-worker’ father John. Orr achieved success as a journalist, becoming editor of the Guardian’s Weekend supplement by 31, and writing a weekly column for two decades thereafter. She was also a child of Scottish industrialisation in the 60’s and 70’s, raised in a religiously divided hometown by parents who reviled her independence, education, and sexual freedoms. Sadly, Orr succumbed to a second bout of breast cancer last year, aged only 57, before her finished manuscript for Motherwell was published.

Motherwell is a poignant family portrait, articulately painted by the late Deborah Orr of a life with ‘house-proud’ mother Win and ‘factory-worker’ father John. Orr achieved success as a journalist, becoming editor of the Guardian’s Weekend supplement by 31, and writing a weekly column for two decades thereafter. She was also a child of Scottish industrialisation in the 60’s and 70’s, raised in a religiously divided hometown by parents who reviled her independence, education, and sexual freedoms. Sadly, Orr succumbed to a second bout of breast cancer last year, aged only 57, before her finished manuscript for Motherwell was published.

Billed as a memoir of self-creation, Motherwell sits alongside other literary accounts of childhood constrained by social circumstances like Kerry Hudson’s Lowborn or Tara Westover’s Educated. Orr’s writing analyses the working-class roots of her parent’s behaviour and how their actions traumatised her, discussing broad-ranging topics in the style of creative essaying but always circling back to the text’s central conceit of ‘The Bureau’, an inherited piece of furniture symbolic of Win’s matriarchal dominance as the latter curated the family’s identity alongside their paperwork.

There are contradictions that Orr admits to – ‘heightened self-love in constant battle with exaggerated self-loathing’ – while others are revealed through language. Recollections that don’t align to her adult identity, for example, are distanced by intellectually witty turns of phrase, like referring to the catholic/protestant divide as ‘Lanarkshire apartheid’, or through journalistic snappiness:

…the phone itself would spring up on its short, aggressive spiral of a cord and whack you in the face. Too light. Rookie design error. Lots of those in 1970s Britain.

In contrast, her memories of rural life on the boundaries of her hometown, which she longed for in adulthood and planned to return to, are captured in lyrically alliterative prose:

So pretty, its leaves so light and effulgent, its little white flowers so delicately traced with their lacy network of purple veins.

Poetic and linguistic constancy therefore yield throughout to the truth that people are messy, complex, and multi-layered. The title itself attests to the wordplay within, naming Orr’s hometown but simultaneously providing a reference pun that Win ‘hadn’t mothered well at all’.

The memoir is thematically heavy, charting the political and geographical undercurrents of Motherwell’s industrial rise and fall, expounding on mental health across de-industrialised townships and within personal familial relationships. Yet as with her childhood, these themes are over-shadowed by the overbearing mother-daughter relationship arc and Orr’s growing conviction that Win’s narcissism contributed to her own eventual diagnosis of complex post-traumatic stress disorder:

I didn’t know, until recently, that denying another person their own feelings is the foundation of all emotional abuse.

Orr skilfully selects discrete observations from her family history, layering them with concerns about class, gender, education, and sexual autonomy, until they build into a crescendo of mental abuse in early adulthood. In these most painful of moments, Orr quotes her mother’s words directly:

“I love you, Deborah. You are my daughter, my firstborn, and I will always love you. But I’m afraid I don’t like you. Not at all.”

Such lines introduce an unreliability to the narration, which Orr herself somewhat concedes when observing it’s ‘hard to know what’s a revelation of hindsight and what’s a projection that helps you to bolster your own story’.

Louise Glück’s essay ‘Education of the Poet’ suggests writing is not simply a decanting of personality to paper, and Motherwell could be entered into the record as proof. ‘Is memoir therapy? Or is it vengeance?’ Orr tellingly asks of her own motivations. Part-meditation, part-psychoanalysis, her essayistic memoir leaves the formation of thoughts on the page as catharsis, humanising her mother’s transgressions through this detailed reportage of lived hardships.

That this first book also represents Orr’s final work must be sad; it captures her rich candour and gracious nature within an intelligent and complex form, it is also clear that so much more could have followed. HannahWhaley

Leave a Reply