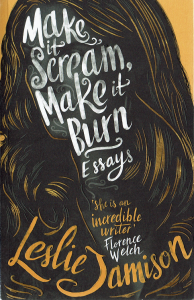

Make it Scream, Make it Burn: Essays

The essay’s star is in the ascendant. While there has been a long—even noble—tradition of essay writing going all the way back to Montaigne’s Essais, many people associate essays with classroom forms of assessment. Yet, of late, more writers have felt emboldened to call their prose ‘essays’.

The essay’s star is in the ascendant. While there has been a long—even noble—tradition of essay writing going all the way back to Montaigne’s Essais, many people associate essays with classroom forms of assessment. Yet, of late, more writers have felt emboldened to call their prose ‘essays’.

Make it Scream, Make it Burn is a triptych of essays; triptych because the three sections are not discrete but woven closely together. The first, ‘Longing’, opens with what seems on the face of it, the weird-and-wacky things other folk get up to. So in ’52 Blue’ Jamison reflects on a singular blue whale which has sparked human responses that border on the obsessive; in ‘Sim Life’ she takes on an online platform that allows individuals to play elaborate fantasy families. Not unlike Louis Theroux’s documentaries, Jamison starts with something odd and, like him, what appears initially as a ‘curiouser and curiouser’ Wonderland world turns into a strangely homely one―for the passions and desires that drive these odd stories are ones that we are all know too well. So in ’52 Blue’, the problems of anthropomorphism and our desire to make meaning from the creature’s presence are both given space and attention. Courting complexity and empathy in equal measure, she writes,

If we let the whale cleave in two, into his actual form [“his whaleness which we can’t know”] and the apparition of what we needed him to become [“our metaphoric employ”], then we let these twins swim apart. We free each figure for the other’s shadow. We watch them cut two paths across the sea.

If ‘Longing’ addresses desire in the stories of others, ‘Looking’, the middle section of this triptych, focuses on the nature of storytelling itself, asking, how do you represent or narrate in ways that capture difference without alienating or estranging? Richly textured and philosophically engaging, ‘Looking’ explores rendering in words and images. ‘Make it Scream, Make it Burn’ (about James Agee’s book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men) and ‘Maximum Exposure’ (about Annie Appel’s photographic record The Mexico Journey) are particularly fine responses to the question ‘What does it mean to make art from other people’s lives?’ Bearing witness—how and on what terms—turns precisely on commitment, making space for stories, enabling them to breathe and grow. In Appel, Jamison sees a transformation of photography from a shoot-and-run affair to something that embraces all the messiness of involvement and exchange. Jamison writes of Appel’s openness others and to risk:

I see cornflakes and cigarette and stubborn wind and laughter. I see everything the photos knew alongside everything they didn’t know yet, and this unknowing is one more definition of love: committing to a story you can’t fully imagine where it begins.

‘Dwelling’, the final of the essayistic triptych, turns the spotlight on the author herself as lover, daughter, stepmother and mother. But here, I missed both the self-conscious divisions between the narrating ‘I/eye’ and the experiencing or narrated ‘I’ of her earlier accounts; I missed the two-way defamilarisation provided by the juxtaposition of journalistic stories of others with Jamison’s more ruminative and philosophical fragments. As a result, these seem less dynamic, and take more well-trodden paths. The more successful of these start outwards in (“Museum of Broken Hearts”), rather than inwards out (“The Smoking Self”).

Jamison’s best essays are complex, layered affairs―thinking to write, and writing to think. Attentiveness to language, to metaphors especially, enables essaying in a different key signature to mainstream journalism; metaphors as words work as bridge between two unlike states (self and others). Attentiveness to rendering becomes a commentary on the ways how art figures the world and how it figures in the world. Leavened with occasional wry humour, Jamison has a sumptuous way with words, raiding both high and popular discourse; her lyric sensibility or punchy journalistic line doesn’t get in the way of storytelling. Overall, this is a pleasure to read, and the effect is that we can’t but be surprised by―and into—life.

Leave a Reply