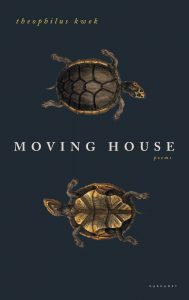

Moving House

Theophilus Kwek is a prolific writer with five collections to his credit. His latest, Moving House, articulates a preoccupation with the themes of migration, belonging, colonial history, and the turbulent politics of the present.

Theophilus Kwek is a prolific writer with five collections to his credit. His latest, Moving House, articulates a preoccupation with the themes of migration, belonging, colonial history, and the turbulent politics of the present.

Kwek is uniquely qualified to tackle these themes. He grew up in Singapore, graduated with a degree in history and politics, and has been involved with the plight of refugees, co-editing Flight, an anthology of poetry in response to the European refugee crisis. As a migrant student in the UK, Kwek suffered the consequences of xenophobia by way of a racist attack, which he touches upon in the poem ‘Occurrence’:

Nothing much then, now nearly unseen –

a cut beneath the eye. A bruise, fading

to skin, frown and furrow, fine print […]

These lines exemplify how expertly a poem can marry form with meaning. The line endings trace the journey from a physical experience to a written one – ‘unseen’, ‘fading’ to ‘fine print’. This movement is felt in other poems as well. ‘Witness’, the opening poem details an accident that happens in the rush of everyday life:

She was already gone. And so were we,

drawn on by the bus’ trajectory […]

The poem’s central ‘[s]teep death’ could be any calamity that we experience, either personally or publicly, which risks erasure by the ‘too usual arc[s]’ of our lives. We might think that routines keep us safe. But, as the poet observes:

This leaving leaves its quiet mark.

[A] rupture

in our time, where past and present

futures meet, stop short. A living fault.

‘Moving House’ examines these comings and goings across time and space. And the marks they leave on life and literature. ‘Camerata’ touches on Aegeus’ grief when he mistakenly believes Theseus dead, leaving the memory of his agony in stone:

he kept

close tally for each month the boy was gone.

We could still see his numbers in the stone,

like a child’s, their straight lines not touching,

endings rubbed out where they were too long […]

The mournful assonance in the above lines draws out pain, like Aegeus’ ‘tally’ lines. We feel with the father the weight of a son’s absence.

In ‘Final Cut’, the speaker is in a salon at Oxford getting a haircut before he needs to catch a 13-hour flight back to Singapore. He muses on the stray strands on the floor,

but he wonders if it is like a dance.

Which are coming, which the leaving ones [.]

Kwek’s fascination for movement draws inspiration from a wide range of experiences in time and space. The scope of this collection extends from Iceland where the landscape is populated with supernatural migrants—

Every man’s heart is fashioned

between these banks. Half will remain

on a path to the ocean, half will long

for an icy shore […]

(‘Notes on a Landscape’)

—to the Gulf of Thailand in 1975, when the Singapore Armed Forces were instructed to detain refugees fleeing Vietnam (‘Operation Thunderstorm’). The poem begins with a question that most governments would do well to ask themselves today:

As if we were not once also torrential,

unstoppable and overboard, our bodies

following our hands across the swell

to this fistful of soil […]

With poems like ‘Lucky’, ‘My Love’ and ‘The Way Light Works’, the collection brings into relief the displacement of essential workers who are often migrants. This focus on displacement feels urgent in the times of COVID-19.

In Moving House, Kwek traces movements which are fundamental to the formation and evolution of countries and cultures. These are movements which inspire headlines, panel shows, and slacktivism. Kwek brings to the conversation, an intelligent and considerate voice – one that is committed to asking questions even if they remain open; in ‘The Way Light Works’, he writes, ‘for now all I have are these questions’.

What could be timelier?

Leave a Reply