My Darling from the Lions

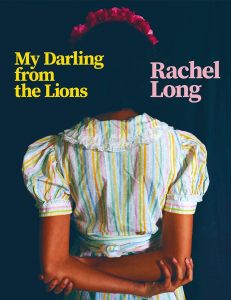

The way we are forced to work around the pandemic unfortunately applies to the launching of poetry publications also; as Rachel Long’s My Darling from the Lions was published at the start of August, chances for public appearances, speaking and promoting her work are all but whipped away. The publication must speak for itself. Long is the founder of Octavia Poetry Collective for Womxn of Colour, and although my electronic copy was without a cover that shows a young woman of colour, themes of race, religion, gender, sexuality and family relationships are evident from the outset.

The way we are forced to work around the pandemic unfortunately applies to the launching of poetry publications also; as Rachel Long’s My Darling from the Lions was published at the start of August, chances for public appearances, speaking and promoting her work are all but whipped away. The publication must speak for itself. Long is the founder of Octavia Poetry Collective for Womxn of Colour, and although my electronic copy was without a cover that shows a young woman of colour, themes of race, religion, gender, sexuality and family relationships are evident from the outset.

Arranged in three sections, ‘Open’, ‘A Lineage of Wigs’ and ‘Dolls’, the collection uses a wide range of forms and structures, all in free verse. The first section begins with a deceptively simple quintet of the same name:

This morning he told me

I sleep with my mouth open

and my hands in my hair.

I say, What, like screaming?

He says, No, like abandon.

Providing us with an intimate glimpse into the speaker’s private life, Long evokes the twisted texture of emotions that come with a relationship behind closed doors. Here, she has opened that door to us with dialogue. As a poem, ‘Open’ is repeated five times at various junctures throughout the first section, albeit with slight alterations in terms of word choice, such as introducing names, the vocative case and different verbs. The last and most noticeable modification results in a septet that closes the section. With each reiteration the meaning of the poem changes, shifting with the context and person to whom it is addressed; ‘Open’ is not as straightforward as it first seems.

The following section, ‘A Lineage of Wigs’, delves into childhood, parental relationships and understanding prejudice. Long explores the relationship with hair and its cultural significance in black communities, and ‘Jail Letter’ provides one such example:

The corners of my eyes have been stitched into my hairline.

All the ‘sheep’s wool’ they love to touch and say eww to at school

has been harvested into rows at the top of my head;

black crown or web.

Tackling the complicated relationship children have with racism and the lack of understanding surrounding black hair in schools, the speaker’s internal struggle with identity, seeing her hair as a symbol of power or a curse, is clear. Long uses puns such as ‘sheep’s wool’ and ‘eww’ to emphasise the cruelty of bullying of children in the playground.

Humour is interlaced with the seriousness of intent in this collection, the witty commentary creating a stark contrast with the difficult topics presented. This is no more evident than in the final section, ‘Dolls’. ‘Interview with B. Tape II’ externalises ingrained social issues using the imagination of a child. In the interview B. says:

Steve tried to threaten Kenny,

Kenny was just retaliating

Just protecting me –Steve wore bright red swim shorts. Too bright.

Everything about those people are so . . .

you know?

The child conceives a dialogue ripe with racial prejudice. The punchline being that B. is Barbie and Kenny is a Ken doll. Steve is black, ‘so black he never bruised’. Evidently exposed all too often to racist behaviours, the speaker has become accustomed to hearing excuses for bigotry and abuse. The unsettling realisation that reality is reflected in what would usually be considered a harmless children’s game, playing at being adults, underscores a deeply discriminatory society. This discomforting humour hits hard.

The praise for this collection is well deserved. It fulfilled something within, each word letting in some light, providing a perspective, teaching, illuminating. It is cathartic, like downing a cool glass of water after going for a run in the summer heat.

Leave a Reply