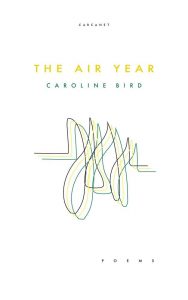

The Air Year

The Air Year is Caroline Bird’s sixth collection with Carcanet. Her most recent and highly successful, In These Days of Prohibition, was shortlisted for the 2017 T.S. Eliot Prize and the Ted Hughes Award. Bird, who published her first collection at the age of 15, displays an astonishing talent and a unique ‘voice’, and is known for her engaging and witty performance.

The Air Year is Caroline Bird’s sixth collection with Carcanet. Her most recent and highly successful, In These Days of Prohibition, was shortlisted for the 2017 T.S. Eliot Prize and the Ted Hughes Award. Bird, who published her first collection at the age of 15, displays an astonishing talent and a unique ‘voice’, and is known for her engaging and witty performance.

The opening poem, ‘Mid-Air’, has an atmosphere of lightness, eroticism and optimism, but this buoyancy is quickly dispelled in the poems that follow. Bird uses thrillingly surreal narratives, as in ‘Nancy and the Torpedo’, where strong sexual imagery meets a Babes-in-the-Woods fairy-tale atmosphere. This is Bird at her most idiosyncratic style; juxtaposing surreal encounters with interior emotions that speak to the reader in new and startling ways.

Yet this collection is altogether ‘flatter’ emotionally than In These Days of Prohibition (one could hardly say ‘darker’). Most of the poems here are one page long or shorter in length, and she has included seven prose poems. Bird’s style and approach really works in prose. In ‘Urban Myth’, she creates an instant picture in the opening lines:

Do you remember the one about the fighter plane during World

War II, riddled with bullets from enemy fire, and the plucky pilot

Who took five packs of Wrigley’s peppermint gum from his pocket

And told his crew to chew – ‘Chew, Crew!’ – so they chewed, ripping

Strip after strip from their foil sleeves to bung the bullet holes […]

‘Dive Bar‘ is a highly crafted poem which depicts the scenario of a closeted lesbian making her way into a basement bar (a Well of Loneliness?). It shows the excruciating self-consciousness of hidden identity, the sensation of watching oneself performing an action in the way that others would watch it—a hall of mirrors, endlessly receding. This is a familiar trope in Bird’s poetry.

‘Checkout’ is irony central. In it, a Life Experience Feedback Form is handed out by an angel to people who have just died:

The angel asks if I have enjoyed

my stay, and I say ‘Oh yes! I’d definitely

come again and he gives me a soft look

meaning ‘that won’t be possible but thanks

all the same,’ clicks his pen and vanishes.

‘Temporary Vows’ is a desolate, disappointed poem, in which the poet conveys a sense of waste, futility and the inevitable breakdown of relationships:

I am proficient at beginnings,

The Air Year: the anniversary prior to paper

for which ephemeral gifts are traditional.

Only after our rings became solid

silver did they truly disappear.

Now the house is a mime scene.

Mime blood all over the floor,

trodden into carpet fibres […]

‘The Girl Who Cried Love’ is another prose poem. In it, the poet delves into a nightmarish psychological place, playing upon the patriarchal terror of the female.

The hovel belonging to the High Priestess of Love was even smaller

And dirtier than I remembered. It looked like an igloo made from shit.

While it’s tempting to speculate that Bird is representing a male fear of the womb here, she never expressly identifies the narrator as male. Is this showing us more of Bird’s disillusionment?

‘Little Children’ reads like a collection of truisms about children, and yet its structure and beautiful wordplay make the views of children seem new again, or freshly realised. After each statement, the reader wants to say ‘YES! That’s exactly what they do!’

‘Emotional Reasoning’ is surely the darkest piece in the collection, another prose poem focussing on a relentlessly bleak and crime ridden location; first of all there is a house, but then the location widens out to a whole town, where unspeakable crimes have been committed, suffusing the entire area with illness and disease. A plague poem, suitable for a plague year.

Leave a Reply