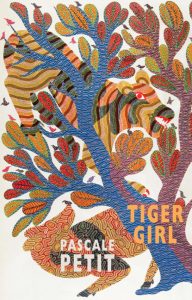

Tiger Girl

Tiger Girl is Pascale Petit’s eighth collection. Her previous works include Mama Amazonica which has won, among others, the Ondaatje Prize. This is a rare win for a woman, and for a poet too since the prize is usually awarded to travel writers. But when it comes to Petit’s work, this honour makes sense. Reading Tiger Girl transports us through portals into pullulating Indian jungles under bright skies, and to dark caves with the beast pacing in the shadows.

Tiger Girl is Pascale Petit’s eighth collection. Her previous works include Mama Amazonica which has won, among others, the Ondaatje Prize. This is a rare win for a woman, and for a poet too since the prize is usually awarded to travel writers. But when it comes to Petit’s work, this honour makes sense. Reading Tiger Girl transports us through portals into pullulating Indian jungles under bright skies, and to dark caves with the beast pacing in the shadows.

Petit’s Welsh-Indian Dadi-maa (father’s mother), the only functional adult of her childhood, is the Tiger Girl of the title. In ‘Her Tigress Eyes’, Petit writes about returning, aged 7, to live with her, speaking no common language but that of survival:

[Y]our hands making the sign for food and milk, just as a tigress attends to her cub, licks her of dangerous scents, and brings her spirit-deer from the meadow.

These lines articulate an important theme of this collection – metamorphosis. Petit’s meditations on her grandmother here, and on other subjects throughout the collection, seem to call on them to reveal their true forms, often hidden to common sight. She continues:

My tawny grandma with as many wrinkles as tributaries in the Ganges, her face the map of India when it’s summer, the map of Wales in winter.

Here, the rolling r’s allow us to be swept over vast spaces – from Wales to the Gangetic plains, pinned only by the frontal assonance of the ‘a’ to underline places.

Other relationships figure in the collection too. In ‘When I was eight my father visited and we went fishing’, the title sets up the reader for a happy memory. The details that follow prove more heart-wrenching for this reason. The poem is in two sentences. The first, a staccato outline of abuse; the second, an untethering of the imagination, an out-of-body experience:

I picture myself sinking into deep water. I open my lips and let the tongue of blackwater tasting of sewage slide in, against the back of my throat, to flood my stomach with ice…

The strong line-endings – ‘tongue’, ‘sewage’, ‘throat’, and ‘ice’ give us the physical sensation of drowning. Here, too, is the theme of the metamorphoses (‘I dreamt of fish with children’s faces…’). Where Ovid’s Procne becomes a nightingale, Petit’s speaker becomes a fish.

A deep love for the natural world is fundamental to the collection. And from this love emerge stunning portraits like the Keats-Shelley Prize winning poem, ‘Indian Paradise Flycatcher’, which silhouettes the bird in flight against the white page:

your tail two comets of ice crystals your face a night- blue sheen as if dipped in starlight…

The craftsmanship of this collection notwithstanding, what moves one most is its sparkling wisdom. A wisdom which neither hectors nor commands. In ‘Pangolin’ where Petit describes in excruciating detail the horrors inflicted on this ancient creature, she pauses to question:

Tell me, you who do not believe in Aryans who once pronounced themselves the master race… what is the mastery that makes us drive other races, other species, to extinction?

Even as she writes unflinchingly about Australian bushfires, species extinctions, and animal cruelty, her voice is gentle, wondering; for example, in ‘In the Forest’, she tells us, ‘with resin from the tree of love/ I glued my lips’. Much like Keats, she allows herself, and her readers, to remain in wonder and mystery. This is rare in an age of passionate misconstructions.

Maybe it is always the first morning of summer

and I’m opening the wings of my eyes.

('Grandala')

And so, with Tiger Girl, Petit succeeds in bringing to us a collection at once personal and universal, terrifying and transcendent, gory and gorgeous. She opens our eyes to beauty and death, fires and stars, transfixes us, and thereby transforms us.

Tiger Girl is mandatory reading.

Leave a Reply